DEAR MAYO CLINIC: My husband is 68 and was recently diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus. The doctor said it was low-grade dysplasia, and that he could be treated for now without having surgery, but that surgery may be necessary in the future. We are worried that his condition will eventually lead to esophageal cancer and want to know if having surgery now should be considered.

ANSWER: Before you and your husband decide on what type of treatment to pursue, there are several factors you need to carefully consider and discuss with a gastroenterologist.

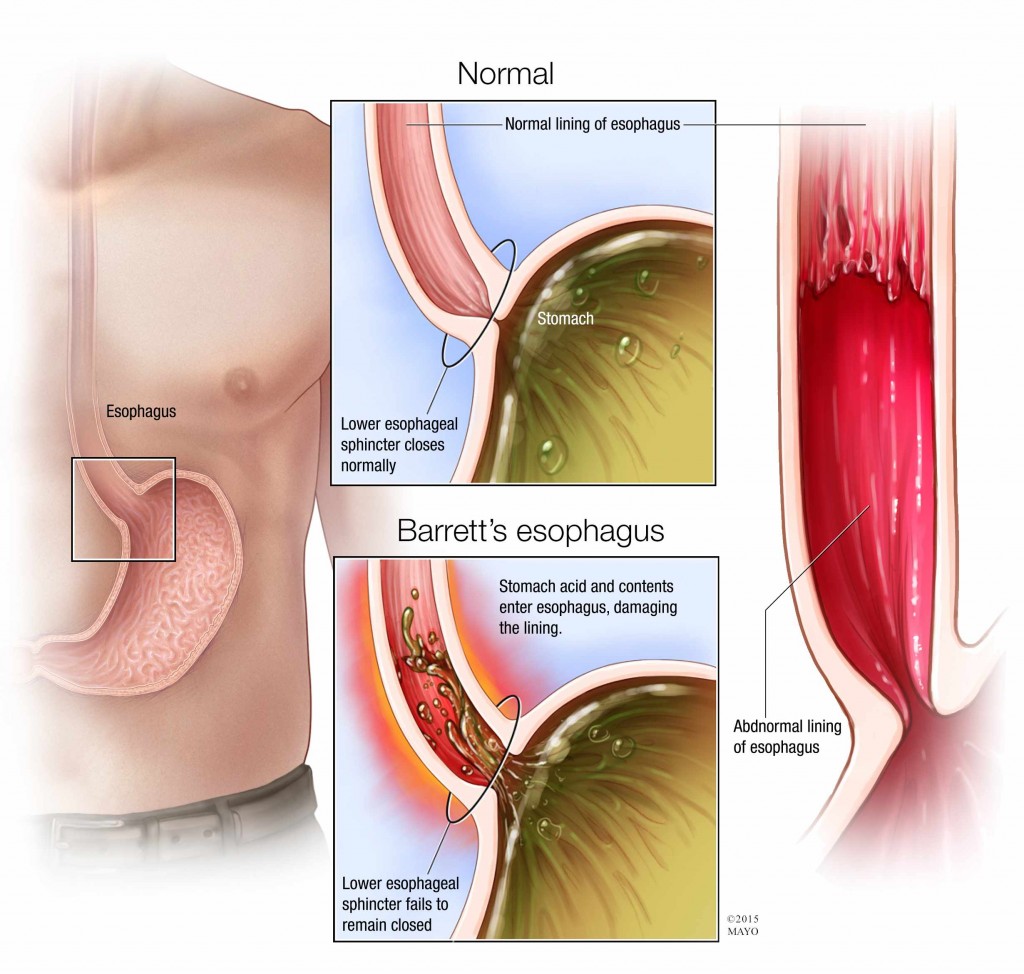

First, the way the condition is diagnosed is critical. In Barrett’s esophagus, the color and composition of the cells lining the lower esophagus change. Normal esophagus tissue appears pale and glossy. In Barrett’s esophagus, the tissue is red and velvety instead. When Barrett’s esophagus is found, tissue samples (biopsies) are taken to determine the degree of tissue change.

Barrett’s esophagus usually falls into one of three categories. If the condition is present, but no precancerous changes are found in the cells when the tissue samples are examined, it is classified as no dysplasia. If the cells show small signs of precancerous changes, it is low-grade dysplasia. If cells show many changes, it is high-grade dysplasia.

To accurately classify Barrett’s esophagus, a large number of tissue samples need to be examined. This ensures that sections of tissue that may have high-grade dysplasia are not missed. The longer the length of the affected tissue in the esophagus, the more important it is that an adequate number of samples are taken. Also, the physician doing the procedure needs to examine very carefully for any lumps or bumps in the esophagus that would make the finding of low-grade dysplasia more worrisome.

Talk to your husband’s physician about how the diagnosis was made. You should also confirm that the biopsies were interpreted by two experienced pathologists, as low-grade dysplasia is often a difficult diagnosis to make. If you like, you can request that your husband’s tissue samples be reviewed by another pathologist to ensure that a proper diagnosis was made. You also may want to consult with an expert in Barrett’s esophagus to review your husband’s situation in more detail.

If the diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia is confirmed, then it is possible your husband may only need monitoring to keep track of his condition at this time. If his condition progresses to high-grade dysplasia, then treatment would likely be recommended. That treatment could potentially include surgery to remove the affected tissue, but that is usually not necessary.

In the past, research seemed to show that the risk of low-grade dysplasia progressing all the way to esophageal cancer was about five percent. However, a very recent study showed that risk to be much higher, at about 20 percent. Those results have yet to be confirmed, though, so the true risk is hard to know. In contrast to the risk of progressing to cancer, some people with low-grade dysplasia appear to have the condition go away without any treatment at all.

To help as you make treatment decisions, you may consider genetic testing. Newer tests that look for genetic abnormalities may be of value in helping to determine whether your husband’s condition is at higher risk of progressing to cancer. It would also be worthwhile to have a discussion with your husband’s gastroenterologist about possible therapies that can be performed at this time to decrease the chance of the disease progressing to high-grade dysplasia or to esophageal cancer. — Kenneth Wang, M.D., Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Related Articles