One in five Americans experiences heartburn at least once a week, and many dismiss the malady as a mere annoyance, choosing to swallow antacids and get on with their lives.

But what they don't know can hurt them. Left untreated, the condition can lead to Barrett's esophagus, which in turn can put patients at risk for esophageal cancer, one of the most deadly forms of cancer.

The reason Barrett's esophagus matters is that patients with at least 3 centimeters of Barrett's esophagus lining have a 30- to 125-fold increased risk of esophageal cancer compared to the general population. Although the cancer risk figures initially sound frightening, only 3 to 10 percent of persons with Barrett's esophagus will develop cancer in their lifetime.

At this weeks national scientific meeting Digestive Diseases Week, Mayo Clinic researchers are presenting new research on the use of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) tests to determine which patients with heartburn might have something more serious.

Right now, our best indicator of the seriousness of Barrett's esophagus is the degree of dysplasia, or precancerous changes, found on a biopsy, says Kenneth Wang, M.D., gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic. However, physicians have to biopsy multiple areas of the esophagus and they still may not detect the pre-cancerous cells. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) could allow for us to change the way doctors diagnose Barretts esophagus.

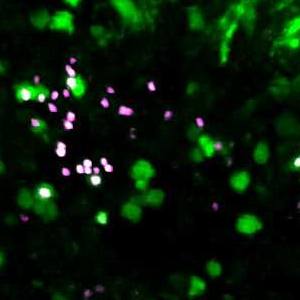

While traditional cytology analysis relies on identifying abnormally shaped cells, the FISH test detects malignant cells using colored DNA probes for specific abnormal genes visible with a fluorescence microscope. Since cancer cells have an abnormal amount of DNA, by FISH these cells show more of the probes compared to normal cells. The advantage of these techniques is that they can easily applied by any endoscopist and the diagnosis can be made on a single abnormal cell.