-

Cancer

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Melanoma can begin in the eye

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: Is it true that melanoma can develop in the eyes? If so, how common is it? How is it treated?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: Is it true that melanoma can develop in the eyes? If so, how common is it? How is it treated?

ANSWER: Melanoma can begin in the eye — a condition called intraocular melanoma. Treatment for intraocular melanoma used to primarily involve removing the affected eye. Now, however, radiation therapy often can be used to treat intraocular melanoma.

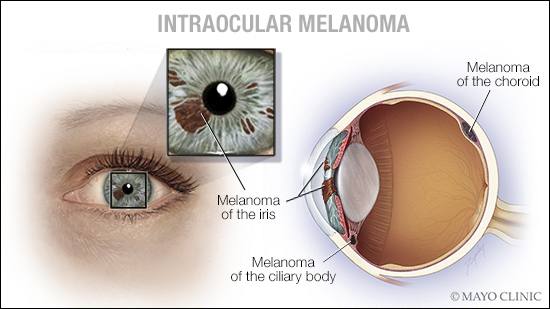

Melanoma is a type of cancer that develops in the cells that produce melanin, the pigment that gives skin its color. The eyes also have melanin-producing cells and can develop melanoma. Intraocular melanomas can be divided into three categories: iris melanomas, ciliary body melanomas and choroidal melanomas. These intraocular melanomas have a different molecular basis than skin melanoma. Therefore, they respond differently to treatment than skin melanomas.

Iris melanomas are the rarest form of intraocular melanoma. Because they affect the colored part of the eye, the patient or a family member usually notices these melanomas quickly. They tend to form in the lower portion of the iris and appear as a spot that’s a different color than the rest of the iris. Iris melanomas also may change the shape of the dark circle, called the pupil, at the center of the eye. Typically discovered when they are still in their early stages, iris melanomas often are treated promptly and successfully.

Of greater concern are choroidal and ciliary body melanomas. Combined, these two categories of intraocular melanomas make up the most common type of cancer that begins within the eye. The incidence is 6 new cases per 1 million adults in the U.S. each year. These melanomas are more common in Caucasians than other ethnic groups by a ratio of 11-to-1. Only 1 percent is associated with a genetic predisposition in patients with risks for other cancers, including mesotheliomas, breast cancer and some forms of skin melanomas.

Ciliary body melanomas form in the muscle fibers around the eye’s lens. Choroidal melanomas develop in the layer of blood vessels at the back of the eye. In some cases, these intraocular melanomas may not cause any signs or symptoms, growing undetected until they are in their later stages. They may be detected earlier, though, when they grow near the center of the field of vision, triggering symptoms such as poor or blurry vision, a sensation of flashes in vision, or the appearance of small spots or specks (sometimes called floaters) within the field of vision.

Treatment for intraocular melanomas depends on the location and size of the melanoma. In the past, eye removal was necessary in many cases. Complete removal of the eye still is sometimes necessary for large melanomas. For smaller tumors, however, surgery to remove the melanoma, along with a band of healthy tissue that surrounds it, may be a suitable treatment alternative.

Radiation therapy also is often an effective treatment option for small- to medium-sized intraocular melanomas. The radiation may be delivered to the melanoma using a method called plaque brachytherapy. It involves placing a small disc, or plaque, containing radioactive seeds on the eye, directly over the tumor. The plaque is held in place with temporary stitches and remains over the eye for several days before it’s removed. The radiation also can come from a machine that delivers radiation therapy directly to the eye, such as proton beam therapy or gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery.

No matter the treatment approach, the chances of the melanoma developing elsewhere — in the remaining portion of the affected eye, in the other eye or in other parts of the body — is the same. Follow-up care to monitor for cancer recurrence in people who have had an intraocular melanoma is essential for 15 years after treatment. — Dr. Jose Pulido, Ophthalmology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota