-

Cardiovascular

Mayo Clinic Q and A: What is a bicuspid aortic valve?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I consider myself to be in good health. I work out several times a week, but recently I began experiencing episodes of shortness of breath after going up and down the stairs in my home. After running on the treadmill a few weeks ago, I got dizzy and fainted. I went to my doctor who told me that I have a bicuspid aortic valve. Can you share more about what this is and if it can be fixed? Also, I have children. Are they at risk for this condition?

ANSWER: It can be a shock to receive a diagnosis that you have a heart condition. The good news is that you should be able to live a healthy and active lifestyle with the right care.

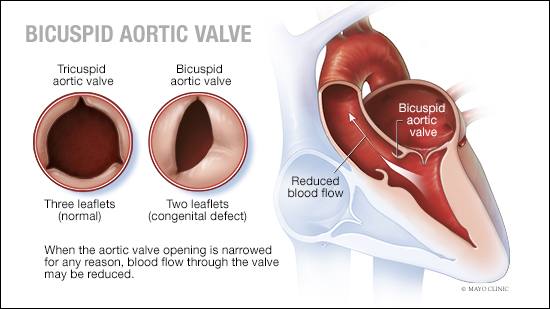

As a reminder, the heart has four major valves. The two valves on the left side of the heart are the aortic valve and the mitral valve, and the two valves on the right side are the pulmonary valve and the tricuspid valve. The aortic valve is the main "door" out of the heart. Blood flows through the aortic valve to exit the heart, and supplies oxygen and nutrients to the rest of the body.

The normal aortic valve has three leaflets, also known as cusps. Some people can be born with one, two or even four cusps of their aortic valve. The most common of these abnormalities is an aortic valve with two cusps — thus, a bicuspid aortic valve.

A bicuspid aortic valve is a common cardiovascular condition, affecting about 1% of the general population. Bicuspid aortic valves are more common in men, but also affect women. A bicuspid aortic valve is a congenital condition, meaning that people are born with two rather than the normal three cusps on their aortic valve. Although bicuspid aortic valves can occur sporadically without any inheritance pattern, the condition also can run in families. Many people can live with a bicuspid aortic valve for their entire life, but there are those who may need to have their valve surgically replaced or repaired.

When people are born with a bicuspid aortic valve, the bicuspid valve typically functions well throughout childhood and early adulthood. When people reach middle age, bicuspid aortic valves can begin to degenerate. Degeneration is normal for aortic valves as people age, but occurs at a younger age in bicuspid aortic valves compared to normal aortic valves.

Degeneration occurs in two forms: narrowing, also known as stenosis; or leaking, also known as regurgitation. People do not feel any symptoms of bicuspid aortic valves until the narrowing or leaking becomes severe enough to affect heart function. At that point, people with bicuspid aortic valves may notice shortness of breath, difficulty exercising, lightheadedness or chest pain. This sounds like what happened in your situation.

If heart function becomes significantly impaired, people can develop heart failure — the symptoms of which include fluid retention, weight gain, swelling in the legs, substantial breathing difficulty and, potentially, even syncope, which means passing out.

Health care providers usually diagnose bicuspid aortic valves with an ultrasound of the heart called an echocardiogram. CT scan and MRI also can detect bicuspid aortic valves. Bicuspid aortic valves often make characteristic sounds when health care providers listen to hearts.

In addition to early valve degeneration, people with bicuspid aortic valves carry a risk for enlargement, or aneurysm development, of the ascending aorta, which is the main blood vessel that carries blood out of the heart. People with bicuspid aortic valves rarely can have narrowing, or coarctation, of the aorta. Echocardiogram, CT scan and MRI can detect aneurysms and coarctations of the aorta. Your health care provider may want to monitor you with scans at different intervals.

Bicuspid aortic valves are more prone to infection than normal aortic valves. Infection of a heart valve is called infective endocarditis. It can have devastating consequences. Infective endocarditis can occur from bacteria that are a normal part of the human mouth. People with bicuspid aortic valves in addition to dental abscesses or other mouth infections carry a higher risk of infective endocarditis. It is critically important that people with bicuspid aortic valves undergo regular dental cleanings and maintain excellent oral hygiene.

People with bicuspid aortic valves need to have examinations from their health care provider and tests to monitor the valve and aorta on a regular basis. Echocardiograms are the most common tests to monitor people with bicuspid aortic valves, but CT scans and MRIs also can serve that purpose. The frequency of monitoring depends on the degree of valve stenosis or regurgitation, ascending aorta enlargement, and a person’s family history. Tests may be necessary as frequently as every six months to as rarely as every five years. Because bicuspid aortic valves can run in families, all first-degree relatives (i.e. children, siblings and parents) of people with bicuspid aortic valves should have an echocardiogram to check for a bicuspid aortic valve and an ascending aortic aneurysm.

There are no medications to treat a bicuspid aortic valve. The only treatment is surgery to repair or replace the aortic valve if the stenosis or regurgitation becomes bad enough, or if the ascending aorta becomes too large.

Not all patients with bicuspid aortic valves will need heart surgery. Studies suggest that up to 75% of people with bicuspid aortic valves will require intervention at some point in their lives. If people with bicuspid aortic valves have regular monitoring and prompt treatment, their lifespans are similar to the general population.

People diagnosed with a bicuspid aortic valve should understand that they will require regular monitoring and may eventually require valve replacement or repair. They should otherwise live an active, healthy and normal lifestyle. ― Dr. Michael Cullen, Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota