-

Cardiovascular

Sharing Mayo Clinic: A heart patient’s fall picks up something big

Mitch Prust has fond memories of spending long hours hiking the trails at his getaway in northwestern Wisconsin, but during a visit in late September, it's what he didn't remember that put him on a new path. It was not hours or minutes; it was just a few seconds. While this was a short lapse of time, the positive result of this experience will last a lifetime.

Around 9 p.m. while walking through the woods with his wife to his residence, he jokingly pretended to hear an animal and sprinted a few yards. He then fell on his face and sustained a bloody nose.

He doesn't recall falling or his wife flipping him over onto his back. He thought he tripped. The couple rested a few minutes, continued home and retired for the evening. The next morning, Mitch woke up with a new curiosity. Did he simply stumble, or was there another reason?

He was asking these questions because he has a serious heart condition.

In 2014, before becoming a patient at Mayo Clinic, the 55-year-old inventor and tech industry executive from St. Paul, Minnesota, was diagnosed with a heart murmur. Three years later, in 2017, Mitch was asked by his new doctor in the same practice how he was managing those initial findings. That's because, in addition to the murmur, he was told for the first time that those earlier tests indicated that he might have a complex disease that affects 1 in 500 people: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

Mitch says that was news to him, and that motivated him to search for answers. "This was super concerning for me because I felt I learned about potentially having hypertrophic cardiomyopathy back in 2014."

After researching centers of excellence on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and reading a story on Sharing Mayo Clinic, Mitch sought care with Jeffrey Geske, M.D., a Mayo Clinic cardiologist. After extensive testing and evaluation, Mitch's questions were answered. And there was no doubt he had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

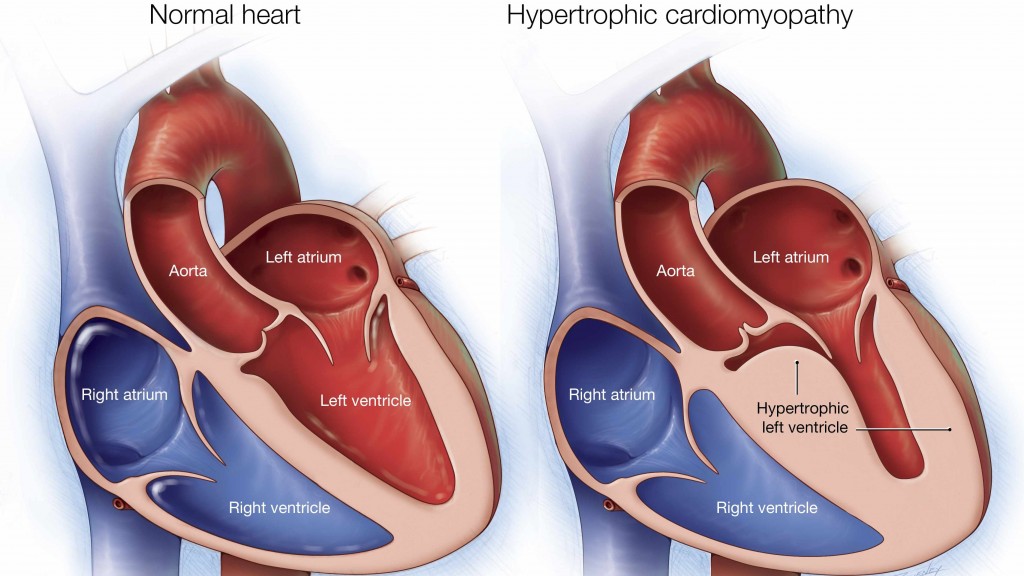

"Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a condition where the heart muscle becomes too thick. Because of this thickening, blood flow exiting the heart can become obstructed. The most common symptoms associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy are chest pain or shortness of breath. However in a small group of patients, unfortunately, the first symptom can be sudden cardiac death," says Dr. Geske.

With the new diagnosis, Dr. Geske and the team designed a treatment plan with Mitch, who has always been active. In high school, he wrestled, played football and ran track. Even as an adult with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, he continued to play in hockey leagues under the close supervision of his care team.

He is also a big fan of the Minnesota Wild hockey team, and it was attending their games that he noticed a steep deterioration in his stamina.

"In the beginning with my diagnosis of HCM, I was asymptomatic. But I noticed that when I'd go up a few flights of stairs at the arena, I felt like I'd hit a wall, and get lightheaded and be on the verge of fainting."

After noticing he was tiring more easily and after more evaluation, Mitch and Dr. Geske determined that a septal myectomy would be his best option. During this open-heart procedure, the surgeon removes part of the thickened, overgrown heart wall between the heart chambers, called the septum. This procedure seeks to improve blood flow out of the heart and reduce backward flow of blood through the mitral valve. Mitch says that after Hartzell Schaff, M.D., a Mayo Clinic cardiovascular surgeon, performed the procedure, he felt better immediately.

Still feeling great about six months after his surgery during a routine checkup, Mitch followed up with Dr. Geske. Mitch's EKG, a test to evaluate electrical signals in the heart, showed that Mitch had developed a left bundle branch block, which is a delay in the pathway of electrical impulses that make the heart beat.

Dr. Geske explained that this is a common finding seen in nearly half of patients who undergo septal myectomy. Although Mitch had a different "electrical fingerprint" after surgery, his heart rhythm was still normal. Dr. Geske asked Mitch if he would be interested in participating in a study looking for abnormal heart rhythms, such as atrial fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy who do not have a history of any abnormal heart rhythm.

Mitch is dedicated to helping others with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, especially contributing to data to learn more about the disease, so when Dr. Geske asked if he'd be interested in the study he said yes.

"I just really wanted to help. I was doing so well. It was to benefit other people, and, you know, there was a chance it could pick something up," says Mitch.

A portion of the study involved implanting a device smaller than a AAA battery under the skin. This device continuously recorded heart rhythm data. While visiting Mayo in December 2020 to take part in another study, Mitch had the loop recorder implanted by Konstantinos Siontis, M.D, Heart Rhythm Services. The placement of that recorder may have saved his life.

About a year later and back to the Wisconsin woods — the day after his fall — Mitch sent a message to Dr. Geske asking if the device indicated any unusual heart activity that night. After receiving the message, the health care team called Mitch, asking how quickly he could get to Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. The loop recorder data showed that Mitch's heart stopped beating for 10 seconds.

After Drs. Geske and Siontis evaluated the data and examined Mitch, he was diagnosed with an episode of complete heart block. "Because of Mitch's surgery, he was more dependent on the other side of his conduction system — the right bundle branch. When this side unexpectedly stopped working correctly, nothing told Mitch's heart to beat. Without the loop recorder, we would not have known what Mitch's heart rhythm was when he passed out. It really clarified what was going on."

To prevent this from happening again, Mitch had a pacemaker implanted right away. "His pacemaker now prevents him from having his heart stop beating again," says Dr. Geske. "I suspect he will do quite well. Patients with pacemakers can lead normal lives. Mitch's surgery was very successful at alleviating his obstruction, but he still needs regular follow-up of his HCM to ensure we keep his heart 'tuned up.'"

Mitch agrees with Dr. Geske and says he is doing quite well these days. He looks forward to creating new memories in the woods of Wisconsin, attending a lot more hockey games and educating others about hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. He wants people to know how to identify symptoms at any age and ways to diagnose and treat hypertrophic cardiomyopathy — all with the goal of doing his small part to save lives and improve the quality of life for fellow patients living with this disease.