Advances in epilepsy diagnostics, treatment return man to quality of life

For years, Eric Walthall of Woodville, Wisconsin, experienced more than 100 debilitating epileptic seizures a month. For more than 20 years, he couldn’t drive. He stopped attending many of his sons' activities because he feared a seizure would cause him to lose consciousness. He separated his shoulder twice and hit his head because seizures caused him to fall.

"I couldn't get through life much more," says Eric, now 53, who was diagnosed with epilepsy at 16. He had tried several medications and procedures, seeking care in five different states, with limited success over more than 30 years.

Still, when Eric came to Mayo Clinic in 2021, he had hope. "I knew Mayo was going to knock it out of the park," says Eric, who is seizure-free after extensive evaluation and eventual surgery.

Eric's complicated case was reported in Epilepsy & Behavior Reports. His treatment included radiofrequency ablation with high electrical current guided by stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG), which uses electrodes placed directly into Eric's brain to find where seizures originate.

Treatment options continue to expand

"Mr. Walthall's case was extraordinarily complex and required close teamwork from a multidisciplinary team," says Brian Lundstrom, M.D., Ph.D., Mayo Clinic neurologist and senior researcher on the report. "Fortunately, combined with recent advanced approaches, we were able to find and treat a specific area of Mr. Walthall's brain and control his seizures.”

Epilepsy affects about 50 million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. For about a third of people with epilepsy, seizures persist despite use of medication. For some people, surgery to remove brain tissue where their seizures originate is not an option because of potential risk to brain areas that control speech and movement.

Before coming to Mayo, Eric had tried various epilepsy treatments. He tried two neurostimulation devices that were implanted and ultimately removed — a vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) device and a responsive neurostimulation (RNS) device. While many patients have success controlling seizures with neurostimulation devices, Eric did not.

He also had undergone extensive evaluations at other medical institutions. Eric's Mayo team incorporated a wide array of data from these previous tests. "It was critical for us to fully incorporate previous data into our current approaches to optimize seizure control for Mr. Walthall and minimize risk to his speech and motor functions from surgery," Dr. Lundstrom says.

Complicated epilepsy case

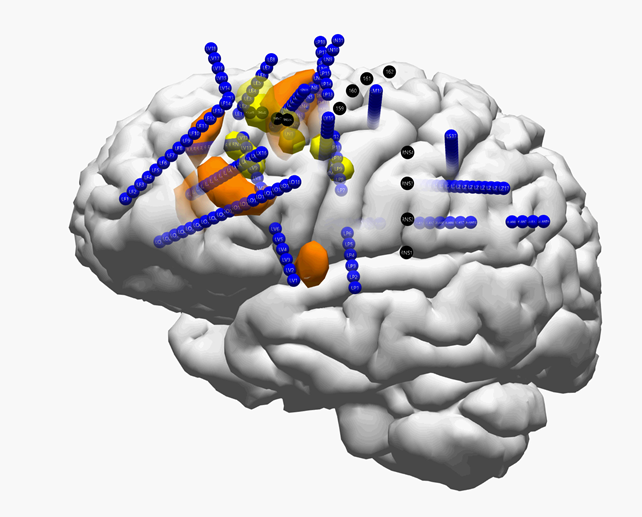

Kai Miller, M.D., Ph.D., Mayo Clinic neurosurgeon, used SEEG — temporarily putting small electrodes directly into Eric's brain to find the origin of Eric's seizures and help plan personalized treatment options. The Mayo epilepsy team read the electrical changes in Eric's brain while he was being monitored in the hospital, narrowing the seizures' origin to a specific region of the brain.

Then, using the same temporary electrodes, Dr. Miller used high electrical current called radiofrequency ablation to treat the brain area that the team identified. For some people, radiofrequency ablation will stop the seizures. But if it doesn’t, surgery still may be performed with no additional risk.

For Eric, the radiofrequency ablation treatment helped temporarily, and this was crucial in confirming the location in his brain for further surgery. He did go on to have a surgery to remove part of his brain tissue where seizures were originating.

"Radiofrequency ablation allowed us to test the effect of disrupting the brain region where we believed the seizures were starting from, using electrodes that were already in place," Dr. Miller says. "The ablation gave us information to help weigh the benefits and risks of removing brain tissue in an open surgery; we always must balance the likelihood of a cure against possible risks of surgery. I'm thrilled that Eric's seizures have stopped and he's back to enjoying an active life."

Brain mapping

New technology has improved even traditional surgery for epilepsy. During the operation, Eric was awake, which allowed innovative brain mapping — using a Mayo-developed software tool — to ensure the surgery was as precise as could be to help preserve important brain functions, including language and movement.

In the operating room, Dr. Miller stimulated Eric's brain directly. Eric could speak with Dr. Miller and Eva Alden, Ph.D., a Mayo Clinic neuropsychologist, who administered tests to Eric and compared Eric’s presurgery responses to his abilities during the surgery.

"By assessing and monitoring Eric's responses during surgery, I could provide real-time feedback about his cognitive performance," Dr. Alden says. "This helped Dr. Miller gauge whether it was safe to continue operating in that part of the brain, or whether removing it could potentially result in a functional deficit of language or movement."

Eric recovered in the hospital for a week and had speech and occupational therapy.

'This is a blessing now'

Today, Eric is back to driving. He and his wife, Melissa — Eric's chauffeur for years — are figuring out their new normal. Eric was able to take a trip to Canada last fall with his hunting buddies. He returned to downhill skiing, a hobby he had given up. Most importantly, he's able to enjoy family time, in the stands at his younger son's high school basketball games or visiting his older son in college.

"There was a lot of emotional pain and suffering, missing out over the years," says Eric, adding, "This is a blessing now. I give all the credit for my healing to my faith in God and the support of my family and friends and doctors."

For Eric, seeing someone else experience a seizure inspired him to share his story. Once, in a patient reception area, he saw a young girl convulse with a seizure. "Boom, she had one. My eyes welled up. I thought, 'If I ever get better, I want to be an ambassador to show what's possible.'"

The realm of what's possible for patients with epilepsy continues to expand, notes Dr. Lundstrom. Including RNS and VNS, there are other forms of stimulation including noninvasive stimulation and deep brain stimulation for epilepsy. In addition to radiofrequency ablation, there are minimally invasive lasers and guided ultrasound treatment. New research includes studies to predict seizures using wearables, like a smartwatch.

"From a research perspective, it is very exciting to see new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches developed every year," Dr. Lundstrom says. "Even better, though, is to see the difference they can make in a patient's life."

Related posts:

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Using lasers on the brain to treat seizures

- Baby a blessing for woman who had deep brain stimulation for epilepsy

- Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: The latest options for treating epilepsy

- Innovative treatment brings relief to man who experienced hundreds of seizures daily