-

Mayo neuroscientists discover unknown brain area involved in movement

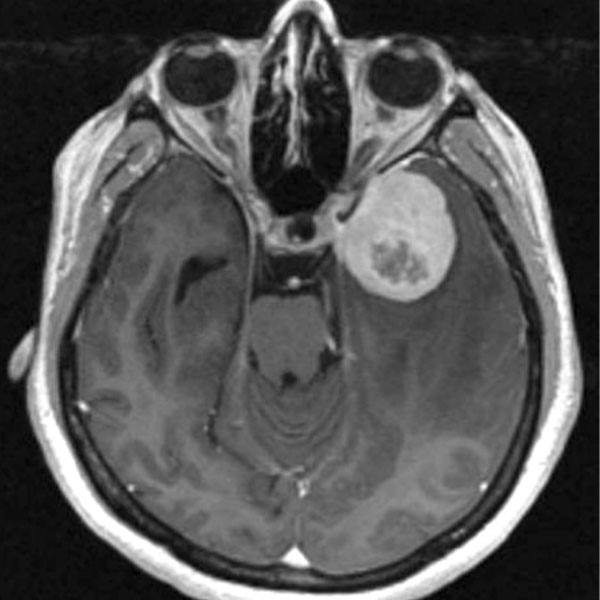

It's long been accepted that the part of the brain called the primary motor cortex controls body movements. Certain groups of cells direct specific movements — for example, of the feet, hands or tongue. The cells of the primary motor cortex are organized as a type of topographical map of corresponding body parts in the central sulcus, a fold in the brain's outermost layer called the cerebral cortex.

Mayo Clinic scientists and their international collaborators were surprised to find that this understanding was incomplete. They discovered this map extends from the brain's surface deep into the central sulcus but is disrupted by an active area for all movements. Areas with this pattern of activity are typically called association areas and previously had been thought to be absent within the fold of the central sulcus. Their findings are reported in Nature Neuroscience.

"We expected to find the known body organization map down to the depths of the brain, but we were surprised to also find this area that is active during all different movements," says Kai Miller, M.D., Ph.D., a Mayo Clinic neurosurgeon and senior author of the study. "Emerging tactics for stimulating the brain to treat movement disorders like tremor may be able to leverage this for better therapeutic response."

The research team had set out to characterize the electrical function of the primary motor cortex throughout its three-dimensional volume. Thirteen patients, ages 11 to 20, participated in the study while they were being monitored as part of their epilepsy treatment. Stereoelectroencephalography (sEEG) electrodes were placed directly into their brains.

Participants performed tasks of tongue, hand or foot movements with rest in between. With a diagnostic procedure called electromyography, the team used electrodes to record the electrical response of muscles during each movement. The tests showed that an area deep in the central sulcus was active during all types of movement, challenging the long-held understanding that tissue in this part of the brain is tuned to specific regions of the body.

Name of new brain area offers historical reference

The research team is calling this area the Rolandic Motor Association (RMA) area. The name comes from the historical name of the central sulcus — the fissure of Rolando, named after Italian scientist Luigi Rolando.

"It disrupts our previous understanding of one of the most fundamental components of the human motor system," says Michael A. Jensen, an M.D.-Ph.D. candidate at Mayo Clinic and first author of the study.

In the future, this finding could affect how surgeries to remove brain tissue are performed or the way brain stimulators are used to treat conditions such as epilepsy or Parkinson's disease, Jensen says.

The researchers are working to characterize the RMA further. They plan to do this by measuring electrical stimulation-based connectivity between the RMA and other brain areas, and by designing more nuanced tasks for patients to perform, investigating in which aspects of movement the RMA acts.

Training physician-scientists

Jensen is part of Mayo's Medical Scientist Training Program, which combines earning a doctorate in the Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and a medical degree in the Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine to prepare students for a career as physician-scientists.

"There is a strong emphasis in Mayo's Cybernetics and Motor Physiology Laboratory on answering both scientifically and clinically useful questions,” Jensen says. “The culture in the Mayo Medical Scientist Training Program fosters this by centering our medical and graduate school curriculum around the needs of patients. That includes everything from classes to scientific journal clubs to events.”

In Jensen’s work alongside Dr. Miller, he interacts with patients and families in the pediatric ICU, monitoring children with epilepsy. “It can be an intense environment, but Mayo does a great job of preparing students to spend one-on-one time with patients,” Jensen says.

That connection with patients is at the core of Mayo research, education and medical practice. "This science is only made possible because of the willingness of our patients and their families to participate in research during a difficult period of their lives," Dr. Miller says. "We are extremely grateful for that.”

This research is supported by the Brain Research Foundation and by the National Institutes of Health.

The authors report no relevant disclosures. A complete list of authors, affiliations and funding is in the research article.