-

The right diet for you… or for your gut microbes?

Article by Sara Tiner

The right diet, obesity and gut health are topics patients, clinicians and scientists wrestle with every day. We want to eat a good diet and lose weight or avoid weight gain, so our health span matches our life span.

The right diet, obesity and gut health are topics patients, clinicians and scientists wrestle with every day. We want to eat a good diet and lose weight or avoid weight gain, so our health span matches our life span.

But statistics suggest we struggle.

To help, scientists are examining how food, our gut, and our weight are related. Purna Kashyap, M.B.B.S. moderated a break out session on personalized nutrition at the Individualizing Medicine Conference 2018,

during which those examinations led to three conclusions that may change the way we look at our food, our gut and our weight loss plans:

- The environment inside our gut is governed by the same rules as the environment outside the body.

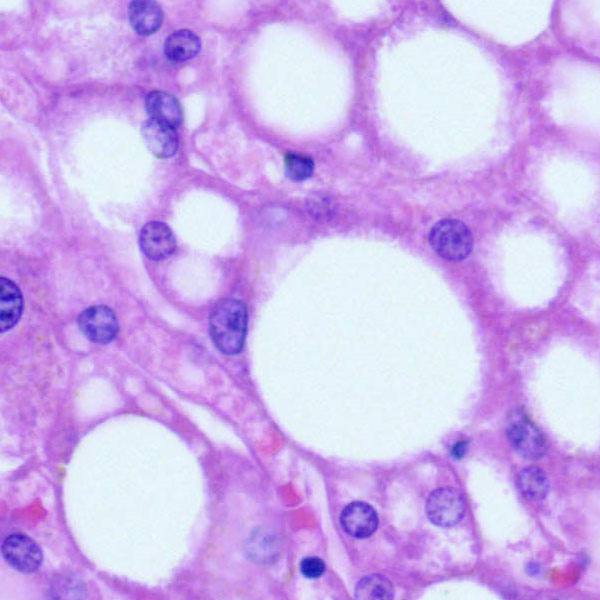

The rules that ecologists have discovered in the natural world hold sway in our gut, too. According to Jens Walter, Ph.D., of the University of Alberta in Canada, while our gut microbes can change, the pattern of change is predictable. For example, where microbes roam (dispersal) and how they win their territory (selection) in the gut, follow the same rules as seeds dispersing from a plant or two seed-eating birds competing for a common food source. This knowledge can help researchers cut through the variation between individuals to understand the underlying similarities in our gut ecosystem.

- Yo-Yo dieting may be due to a memory of famine in our gut microbes.

While science often examines what leads to obesity, patients are often already there. We typically need to lose weight and keep it off for health reasons. But keeping weight off is difficult and researcher Christoph Thaiss, Ph.D., of the University of Pennsylvania wanted to know why. In a series of mouse experiments he and his team replicated yo-yo dieting and discovered that the microbiome remembers feast and famine, and adjusts accordingly. After weight loss, when mice were given a high-fat diet, they regained more weight faster than they had in the first round of weight gain. The researchers then delved into the specifics of what changed in a post-obesity mouse gut and identified two molecules that were lost: apigenin and naringenin. These plant-derived flavonoids are associated with the tendency to maintain a low weight over time, says Dr. Thaiss, and when mice were supplemented with both in their diet, the mice were able to "forget" the period of obesity and avoid regaining weight. Dr. Thaiss explained that one theory is that this mechanism might be an evolutionary response to fluctuating environmental conditions. In forthcoming research, Dr. Thaiss is examining this effect in humans.

- Eating food your gut microbes want can help keep blood glucose levels stable.

Humans have been in pursuit of the best diet ever since we had a choice in the matter. But despite a long and vigorous effort, the best diet eludes researchers, said Tali Raveh-Sadka, Ph.D., director of research at DayTwo. The company is one of a few new ventures that gather data from consumers, digest it in a computer algorithm, and report back personalized food recommendations. When participants in one trial were fitted with a continuous glucose monitor, the variety of responses was high. One person's blood sugar spiked when consuming a banana but not a cookie, explained Dr. Raveh-Sadka, but another participant had the opposite response. The researchers found that when participants ate the "good for their microbiome" diet, their microbiome shifted and their blood sugar readings remained stable.

Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine sponsored the conference, which was held Sept. 12-13 in Rochester.

More conference-related highlights

- CIM CON day 1 – Precision cancer care: ‘So much power’

- CIM Con day two: Unlocking the mystery of rare diseases

- CIMCON 18: how genomics discovery is transforming individualized care and the path forward

- 6 ways individualized medicine in advancing patient care

- Mayo Clinic Minute: What is the microbiome and how does it affect your weight?

Join the conversation

For more information on the Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine, visit our blog, Facebook, LinkedIn or Twitter at @MayoClinicCIM.

Related Articles