-

A diagnosis and hope for a journey back to health

JoAnne Michael doesn’t remember much about 2018. That year, at the age of 45, she began having cognitive issues, including memory loss, confusion, and brain seizures. Her symptoms were caused by a rare autoimmune disease called GABA-A-R antibody encephalitis, but JoAnne, an environmental consultant from Carson City, Nevada, didn’t know that until later, when a sample of her cerebrospinal fluid was sent to Mayo Clinic’s Neuroimmunology Laboratory in Rochester, Minnesota. The lab only did research testing for the disease at the time, so her sample was sent to a lab in Spain for additional testing. But JoAnne’s case would go on to inspire Mayo Clinic to validate its own test for GABA-A-R and become one of the only labs in the world to conduct diagnostic testing for GABA-A-R antibody encephalitis.

"The damage from autoimmune encephalitis was to my short-term memory, and I don’t have any memory of pretty much all of 2018, prior to being diagnosed and treated," says JoAnne, who only knows what happened thanks to the rigorous notes her mother kept throughout her ordeal. "So apparently, in early November 2018, I had called my mother and told her I was having dizzy spells at work and having a hard time remembering things."

Not long after this, JoAnne and her son Jacob flew to Denver to visit her mother and celebrate a couple of family birthdays. Everything seemed fine at first, but the next morning, something became very wrong. "I woke up and I didn’t remember where I was," JoAnne says. "I asked my mother how I got there and what I was doing there, and she told me. A half an hour later, I asked her those same questions again, and she became concerned."

When JoAnne’s confusion didn’t improve, her mother took her to the emergency department at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital, where she had worked as a nurse practitioner until her recent retirement. ER doctors there initially thought JoAnne’s symptoms could be from substance abuse, which can be a common misdiagnosis given the mental agitation and, in some cases, psychosis caused by encephalitis. "If you go to an ER, people aren’t initially thinking to look for autoimmune encephalitis, and it’s scary,” JoAnne says. “It’s scary what you might have to go through before you get an accurate diagnosis.”

Puffy clouds in her brain

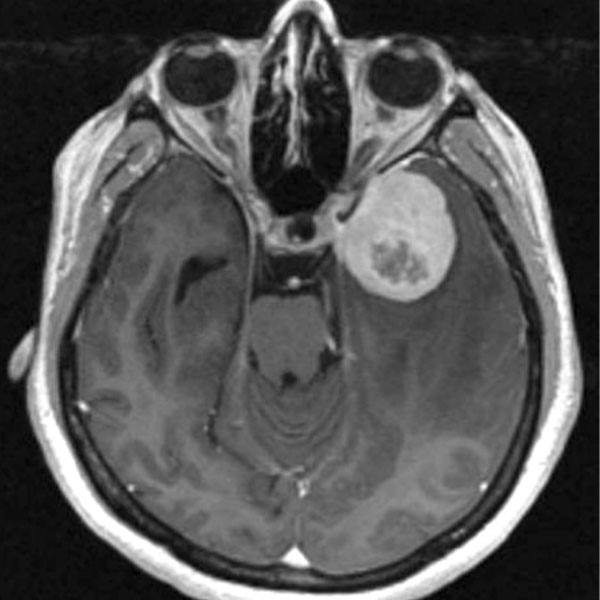

When JoAnne tested negative for drugs, she was admitted to the hospital for a battery of tests. "The MRI showed these spots all over my brain," she says. "They looked like little white puffy clouds, and they were calling them lesions … so they knew something was wrong with my brain."

JoAnne’s lesions were her immune system’s response to a buildup of antibody proteins.

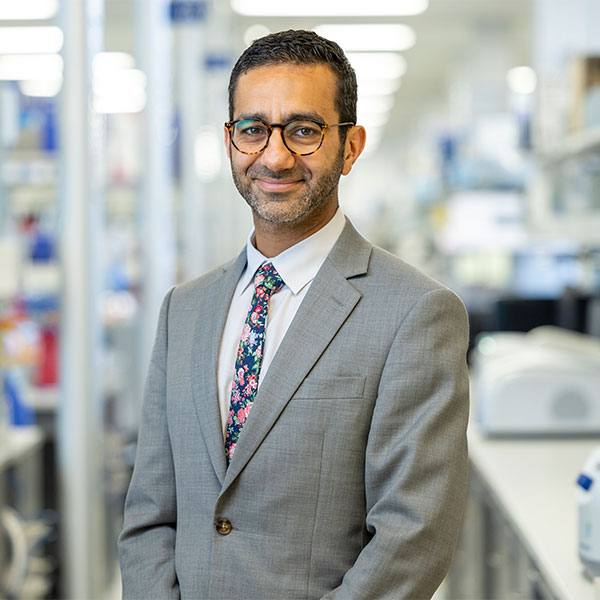

"For GABA-A receptor patients, the lesions particularly affect the limbic region of the brain, which is in the temporal lobe," says Andrew McKeon, M.B., B.Ch., M.D., who's not only director of Mayo Clinic's Neuroimmunology Laboratory but also the Mayo Clinic neurologist who would accurately diagnose JoAnne. "That’s how we recognize it on imaging, by these multifocal brain lesions. In some respects, they almost look like multiple sclerosis, except the lesions are very big."

Dr. McKeon continues, "The lesions don’t just occur in the limbic area. Patients also get them in the frontal lobe, or the parietal or occipital lobes, so they're related to all these different areas of the brain. Clinical symptoms can result in confusion, memory problems, and personality changes. Or a person could have visual or auditory hallucinations."

After a week of other tests that came back negative, doctors suspected encephalitis but did not know the cause. JoAnne underwent a lumbar puncture, and a sample of her spinal fluid was sent to Mayo Clinic for testing. She was then prescribed an anti-seizure medication and sent home. Over the course of the next week, JoAnne was “a wreck,” she says. “I was crying all the time and I had such anxiety. The brain seizures were causing everything to smell like burning rubber and everything tasted horrible. I was not eating or drinking. My mom called the hospital and said, 'She needs to be readmitted.'"

At UCHealth, additional EEG monitoring showed JoAnne's seizures were much worse than they had been initially, so she received more anti-seizure meds. Her latest spinal fluid tests showed the presence of an antibody called GAD65, so her neurologist at UCHealth began treatments for autoimmune encephalitis. "But I was told this antibody didn't really account for the severity of my brain lesions or symptoms," JoAnne says.

JoAnne would go on to receive five days of plasma exchange treatments — a procedure in which a machine separates plasma from blood cells, the blood cells are then mixed with a liquid to replace the plasma, and then returned to the body without the harmful antibodies that were affecting her brain. JoAnne also received high IV doses of steroids and rituximab, an immunosuppressant. These treatments are common for autoimmune encephalitis; thus, they were administered even before JoAnne’s antibody subtype was known.

Tears of relief

JoAnne was also put on an anti-anxiety medication and began to feel better. But after another MRI showed the blotches were still in her brain, doctors "wanted to do a brain biopsy on the lesions," she says. "And my mother, the nurse, was like 'No way. We're getting a second opinion.'"

And so, on Jan. 28, 2019, JoAnne met Dr. McKeon in his office at Mayo Clinic.

"When she saw me the first time, I was certain she had autoimmune encephalitis," Dr. McKeon says. "But I also suspected she had the GABA-A-R subtype on the basis of her clinical presentation and MRI findings. At that time, the testing was not clinically available in our lab, so I sent her samples (serum and CSF) to a lab at the University of Barcelona, where the disease was discovered, and they confirmed this diagnosis."

After JoAnne tested positive for the GABA-A-R subtype, Dr. McKeon explained that she would need to continue the rituximab and steroids to decrease the likelihood of relapse. The rituximab depleted her B lymphocytes, aka B cells, which mature into plasma cells and are the antibody "factories" of the immune system.

When JoAnne received her exact diagnosis and long-term treatment plan from Dr. McKeon, she felt relieved and hopeful for the first time in a long time. "I'm not saying the care I received at the University of Colorado wasn't great," she says, "but I felt like they weren't a hundred percent sure how to test or treat me. Then I saw Dr. McKeon and I felt like, 'Oh my God, he knows exactly what he is doing and has an exact plan for how I'm going to get better."

JoAnne was on three anti-seizure medications by the time she came to see Dr. McKeon. Over the next two years, he not only weaned her off of those medications but also the steroids and rituximab. "What we've typically found is that, with these autoimmune encephalitis cases where seizures occur, the seizures don't really respond very well to just standard anti-seizure medicines," Dr. McKeon says. "We generally don't get the seizures under control until we treat with immune therapy."

JoAnne was able to coordinate continued monitoring scans and treatments through her neuroimmunologist at UCHealth in Colorado. She received her last therapy infusions in December 2020.

A study inspired by a rare patient case

JoAnne's case — only the second Dr. McKeon had ever seen in his practice — prompted the Neuroimmunology Laboratory to do a study to validate its own testing method for GABA-A-R antibody encephalitis (Mayo IDs: GBACC and GBACS).

"There was demand from other providers around the country for Mayo to start offering this test," Dr. McKeon says. "So, after we saw JoAnne, we did a study so that we could find more cases in the lab based on assessing all of our stored samples.

Because when we look down the microscope at mouse brain tissue, we can see a GABA-A-R staining pattern that we saw in JoAnne’s samples. And then we're able to say, 'Well, how many other samples do we have that look just like JoAnne's?'"

The study, done in collaboration with Oxford University and the German company Euroimmun, pulled together a list of patients who, like JoAnne, were confirmed to have GABA-A receptor antibodies. Dr. McKeon's Neuroimmunology Laboratory then worked with Euroimmun to collect more commercially available GABA-A receptor slides with which to validate the test, and thus move it from a research environment to a clinical test. That’s where Eati Basal, Ph.D., a senior developer in the Neuroimmunology Laboratory, came in. "I tested serum and CSF from 190 healthy individuals and 132 patients with other neurological diseases," Dr. Basal says. "All control samples were negative on the cell binding assay. After validation we found this test to be 100% sensitive and specific.

"Identifying such antibodies helps doctors differentiate autoimmune encephalitis from other neurological conditions like infectious or metabolic encephalopathies, where treatment approaches differ."

Luck was on her side

JoAnne is now off all her medications and after a six-month leave, back to the environmental consultant job she's had for the past 20 years. Her anxiety is gone, and she’s back to enjoying life and raising her 16-year-old son. She considers herself fortunate to have been at her mother’s house when her symptoms peaked.

"I have recovered completely, and I'm very lucky that I was diagnosed early,” she says. “And to have a mother like mine, a nurse practitioner who knew what to do, who didn’t let them do a brain biopsy on me. She sent me to Mayo Clinic."

For more information on GABA-A receptor antibody testing from Mayo Clinic Laboratories, visit news.mayocliniclabs.com/neurology/autoimmune-neurology/encephalopathy.

This article first published on the Mayo Clinic Laboratories blog.