-

Discovery Science

Spatial biology puts potential disease targets in their place

"Location, location, location" may be a familiar mantra in real estate, but in the world of biology, it's proving just as essential. Spatial biology is a rapidly evolving field that maps the precise location of molecules within cells and tissues. It is changing the way biomedical research is conducted, spurring advances in our understanding of health and disease.

"Spatial biology allows us to study how the local environment influences cellular interactions and behavior," says Tamas Ordog, M.D., professor of physiology at Mayo Clinic and director of the Spatial Multiomics Core. "In all honesty, you can hardly find a problem in biology and medicine that is not a spatial problem."

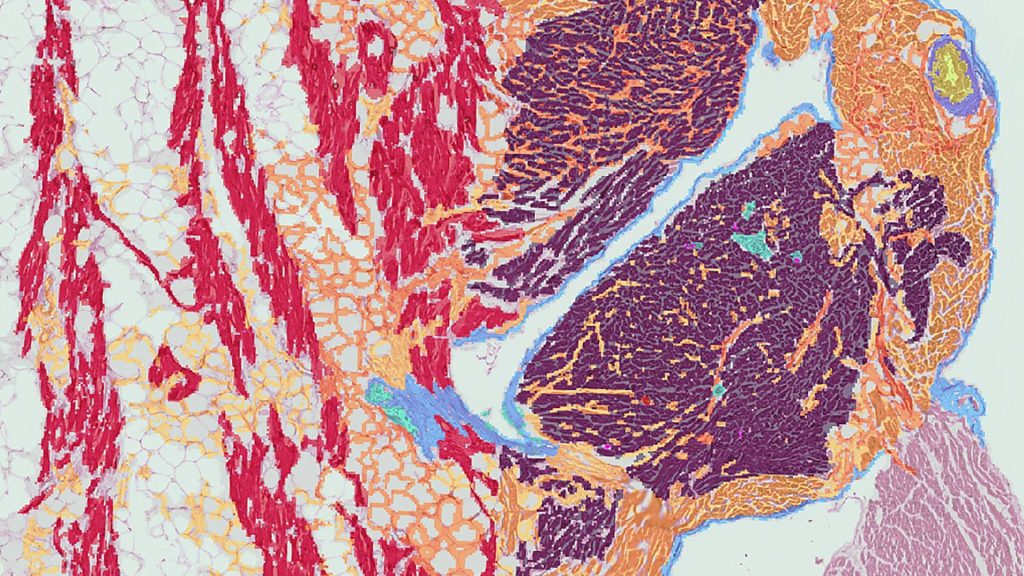

Unlike traditional methods that analyze biological samples in bulk or as single cells, spatial biology uses sophisticated techniques to study molecules in their natural context. The approach marries old-school histology methods involving stains and microscopy with modern-day tools like sequencing and mass spectrometry.

For example, researchers can attach unique molecular "barcodes" to specific targets, such as RNA or proteins, while preserving their position within the architecture of the tissue. They then use high-resolution fluorescent microscopy to "read out" the barcodes to identify the tagged molecules at their location.

Alternatively, they can incorporate location barcodes into the "libraries" of molecules collected from the histological specimens, allowing the simultaneous detection of the targeted RNA or proteins and their location by sequencing. They then decode the barcodes associated with the molecules and combine that information with the spatial data to create maps showing how the molecules are spread across the tissue.

Dr. Ordog says he and his team often refer to their work as "spatial multi-omics" because it integrates multiple layers of "omics" data (such as genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics and proteomics) with spatial information.

"Soon, we will be able to generate an insane amount of information within a very short time with the technologies out there," he says.

This information — which charts where specific molecules are located and how they interact in space — gives scientists a much more detailed, dynamic view of biology. It's particularly transformative in studying diseases like cancer, where the tumor microenvironment plays a key role in disease progression and treatment response.

"Cancer is often a mass of tissue, and the cells that sit inside can behave quite differently depending on whether the tumor is infiltrated by immune cells or only surrounded by them," says Dr. Ordog. "Spatial biology can help us interrogate these interactions."

This emerging discipline can also help researchers tease apart the multiple cell types that make up atherosclerotic plaques, a key feature in the development of cardiovascular disease. And, in the case of Dr. Ordog's own research, it can give insight into how cell-to-cell interactions give rise to diabetic complications of the gastrointestinal tract.

"In diabetes, metabolic dysfunction influences various regulatory cells in the muscle layer of the gut," he says. "We can use spatial biology to assess which cells are more prone to metabolic damage than others."

By revealing how cellular environments shape various biological processes, Dr. Ordog says spatial biology can contribute to the understanding of disease and lead to more precise, personalized medical treatments.

"We can apply these sophisticated discovery techniques to routine patient samples, and in this way shorten the time it takes to translate basic research findings into advances in clinical care," he says.