-

Construction worker rapidly loses ability to walk – Mayo Clinic researchers discover the cause

José Villalta prided himself on providing for his wife and son, first by working construction jobs and then by canning vegetables at Faribault Foods. He was known for being strong and capable, with dark eyes and an easy smile. But in his early 40s that changed, and quickly. "I don't feel the same," he told his wife, Sylvie. His muscles, once one of his defining features, grew progressively weaker. He had trouble walking. Within months, he had to use a cane, then a wheelchair, to get around.

Doctors told him to take more vitamins. They tried acupuncture and electroshock therapy. A specialist biopsied a piece of his leg muscle but could not determine the cause of his deteriorating health. By the time he made his way to Mayo Clinic, he could no longer muster the strength to lift his arms or even hold up his head. "He was like a puppet," says Sylvie.

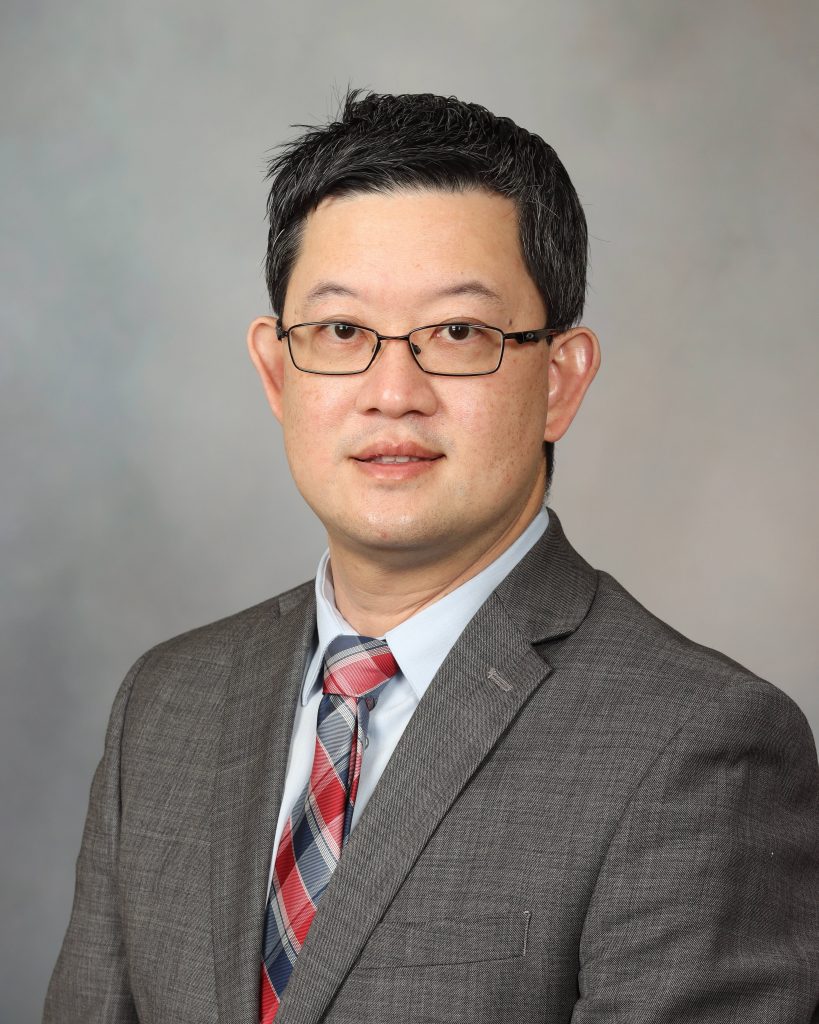

Ashley Santilli, M.D., the clinical fellow at Mayo Clinic assigned to his case, told the family not to lose hope. "She was really persistent," recalls Sylvie. "She said 'We will get to the bottom of this — we will figure out what's wrong.'"

Integrated know-how

At the time, Dr. Santilli was training under Teerin Liewluck, M.D., a neurologist who had trained under the late Andrew Engel, M.D., a pioneer of muscle disease research. Over nearly six decades at Mayo Clinic, Dr. Engel discovered several new neuromuscular disorders and identified the underlying mechanisms of many others.

"One thing he always told me was that he was still learning, even after all those years," says Dr. Liewluck. "He taught me that I need to keep an open mind, because there's always new things to learn and discover."

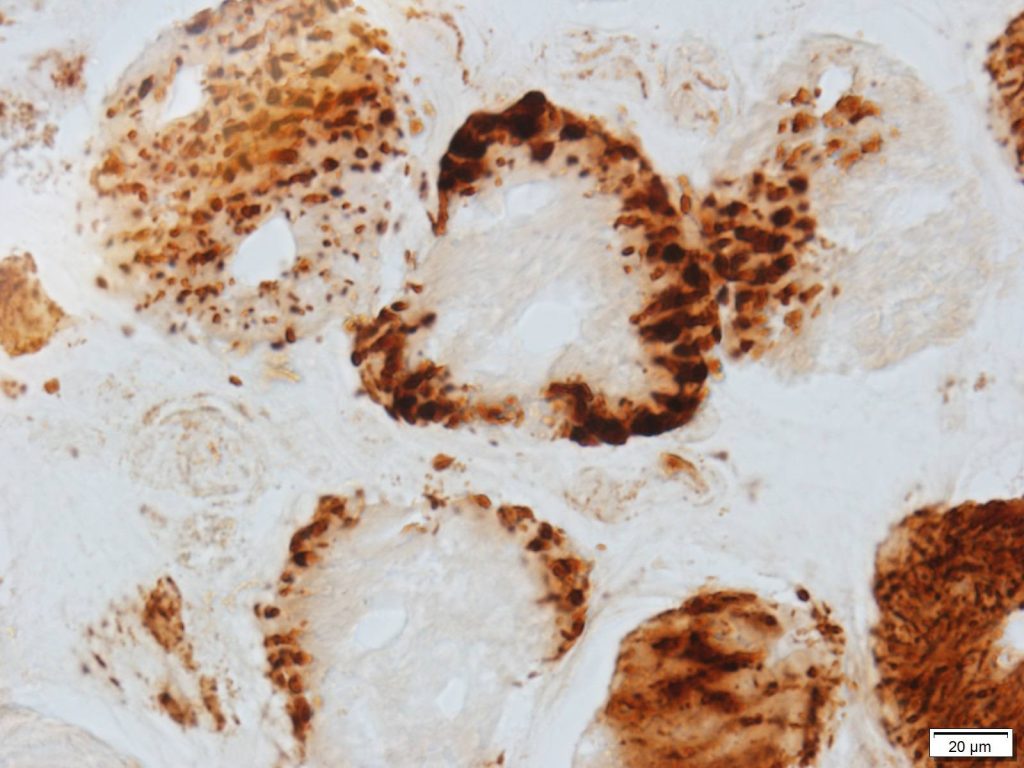

Because Villalta's mysterious illness arose rapidly and later in life, Dr. Liewluck thought the cause was probably not genetic. Congenital muscle diseases typically emerge slowly in early childhood. But when he looked at Villalta's muscle biopsy under the microscope, he was surprised to see abnormally large mitochondria, the energy-producing structures often called the "powerhouses of the cell." Giant mitochondria (also known as megaconia) are associated with a type of congenital muscular dystrophy caused by mutations in a gene called CHKB.

To make sure they were not missing a new presentation of this incurable condition, the team requested genetic testing, which confirmed that Villalta did not harbor any suspicious CHKB variants. So they returned to the biopsy in search of more clues.

"The unique thing about neuromuscular medicine at Mayo is we get specific training in diagnostic tests, like biopsy interpretation and EMG," says Dr. Santilli, referring to electromyography, a test that measures muscle response to nerve stimulation. "You get to be the whole provider for a particular patient, instead of relying on other specialists to help us interpret those tests."

A new disease

Villalta's case gave Dr. Liewluck a sense of déjà vu. He recalled another patient, years earlier, who was part of a study on a severe form of muscle inflammation. That patient's biopsy also was marked by giant mitochondria. The patient's story was only pieced together later: an adult who developed muscle weakness, but whose illness was complicated by an underlying cancer. Treated by another physician, the patient initially improved with immunotherapy, but ultimately the cancer claimed her life.

To better understand Villalta's muscle disease, the researchers performed a series of special stains on his biopsy, each revealing various aspects of muscle structure and pathology. In addition to the unusually large mitochondria within his muscle fibers, they found evidence of inflammation, indicating an autoimmune process was at play. The team believed that Villalta's immune system was mistakenly attacking his muscles. If they were right, then immunotherapy might help him regain his strength.

"We couldn't guarantee or predict the outcome," says Dr. Liewluck.

They told Villalta that he would be the first patient they treated with this new disease, which they called immune-mediated megaconial myopathy (IMMM). They treated him aggressively with regular rounds of intravenous immunoglobulin and steroids. And he got better.

Before treatment, Villalta's levels of creatine kinase, a blood biomarker commonly used to monitor muscle damage, were sky high. With treatment, those levels dropped back within the normal range, suggesting that his overactive immune system had been put in check. More importantly, Villalta felt stronger and required less assistance, showering on his own, tinkering in his garage — even driving himself to rehab.

"To be able to help him, even in a small way, to get back some of that independence that he lost, to get back to doing things that he wants to be doing, was amazing...That is 100% why I went into medicine."

Ashley Santilli, M.D.

Unfortunately, Villalta's illness may have gone too long without treatment to allow a full recovery. Chronic inflammation and repeated muscle damage can gradually lead to the replacement of healthy muscle tissue with fat and scar tissue.

"That gives you evidence that you need to catch these cases earlier," says Dr. Liewluck.

Earlier answers

The team turned to the Mayo Clinic Muscle Pathology database to see if they could find other patients with this new disease within recent years. They identified two more patients, who shared the same distinctive features — profound muscle weakness in adulthood, strikingly enlarged mitochondria, inflammatory reaction in muscle tissue and elevated creatine kinase levels. Working in collaboration with an outside institute, they uncovered a third case. Along with Villalta and the case from the prior research study, the count had risen to five. Villalta and the two newer patients, all of whom received immunotherapy, responded well to treatment.

Now, Dr. Liewluck is delving deep into Mayo Clinic's extensive muscle tissue repository, combing through biopsies that span not just recent years, but decades, in search of other overlooked cases — patients who may have had IMMM long before it was recognized as a distinct entity.

"I actually think there might be many more than we know," says Dr. Santilli.

Interestingly, all the patients they have identified thus far have also had some form of pancreatic disease, such as pancreatic cancer or pancreatitis. Though the link is not entirely clear, the pancreas expresses high levels of choline kinase beta, the same protein that is disrupted in CHKB-related muscular dystrophy. Dr. Liewluck is collaborating with neuroimmunologist Div Dubey, M.B.B.S., to try to identify the antibody that triggers the immune attack, ultimately causing disease.

Once they find that autoantibody, they can test for it in the blood to diagnose more patients with IMMM. For now, they will have to rely on their expert review of muscle biopsies combined with clinical observations.

Though Villalta is not back to his old self, he is happy that his case has already helped others. And he is making the most of the strength he has.

By last spring, Villalta had recovered enough to travel to his home country of El Salvador. His family helped him take a walk on the beach and watched over him as he swam in the ocean. Until recently, it was more than he thought was possible.