Howard Snitzer will be the first to tell you he’s a lucky man.

“I just wish I’d won the lottery instead,” he says, jokingly. But Snitzer knows his good fortune netted him something much more valuable: his life.

Snitzer, a 54-year-old chef, miraculously survived a cardiac arrest thanks to a flawless and unrelenting response from nearly two dozen emergency personnel, including many volunteer first responders. The group took turns performing CPR on Snitzer for 96 minutes, more than 30 minutes longer than previously documented out-of-hospital cardiac arrest durations.

Snitzer’s story begins one cold evening in January, when he headed to Don’s Foods in rural Goodhue, Minn., to buy a tank of propane for his grill. But Snitzer never made it inside. Instead, he experienced cardiac arrest and fell to the ground on the sidewalk just outside the store.

Veteran first responders

Here’s where his luck starts to change. From inside Don’s, clerk Carol Skrypek and shopper Candace Koehn saw Snitzer fall. Skrypek immediately called 911. Brothers Roy and Al Lodermeier — veteran first responders — came running from their auto shop across the street.

Al Lodermeier and Koehn, a CPR-trained corrections officer, began performing CPR, while Roy Lodermeier went to the Goodhue firehouse to get a rescue truck and gear. Soon, volunteer firefighters, police, and rescue squads from the neighboring towns of Zumbrota and Red Wing arrived.

After 34 minutes, a Mayo One flight crew landed at the scene and was stunned to see the long line of rescuers taking turns performing CPR.

“Everything had gone right before we arrived,” says Bruce Goodman, a flight paramedic. But as the minutes ticked by, he began to lose hope.

“We couldn’t get Mr. Snitzer out of v-fib,” says Goodman. “V-fib” — ventricular fibrillation — is an abnormal heart rhythm that prevents the heart from pumping blood. Electrical shocks from a defibrillator can sometimes correct the rhythm. So can certain medications. Snitzer’s rescuers tried both, shocking him 11 times and pumping numerous drugs into his system. Still, the abnormal rhythm persisted.

Goodman called Roger White, M.D., an anesthesiologist at Mayo Clinic and a world-renowned expert in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest intervention, four times as they worked on Snitzer.

By the last call, “I was pretty discouraged,” says Dr.White. “We were right against the wall.”

A calculated risk

Finally, Dr. White advised a calculated overdose of the heart drug amiodarone, followed by another shock with the defibrillator. The combination worked.

Goodman wasn’t sure that was a good thing.

“I thought we’d revived someone who in my opinion couldn’t survive what he’d been through,” says Goodman. “He’d been down an hour and a half. The likelihood of him walking out of the hospital with any kind of life in my mind was zero.”

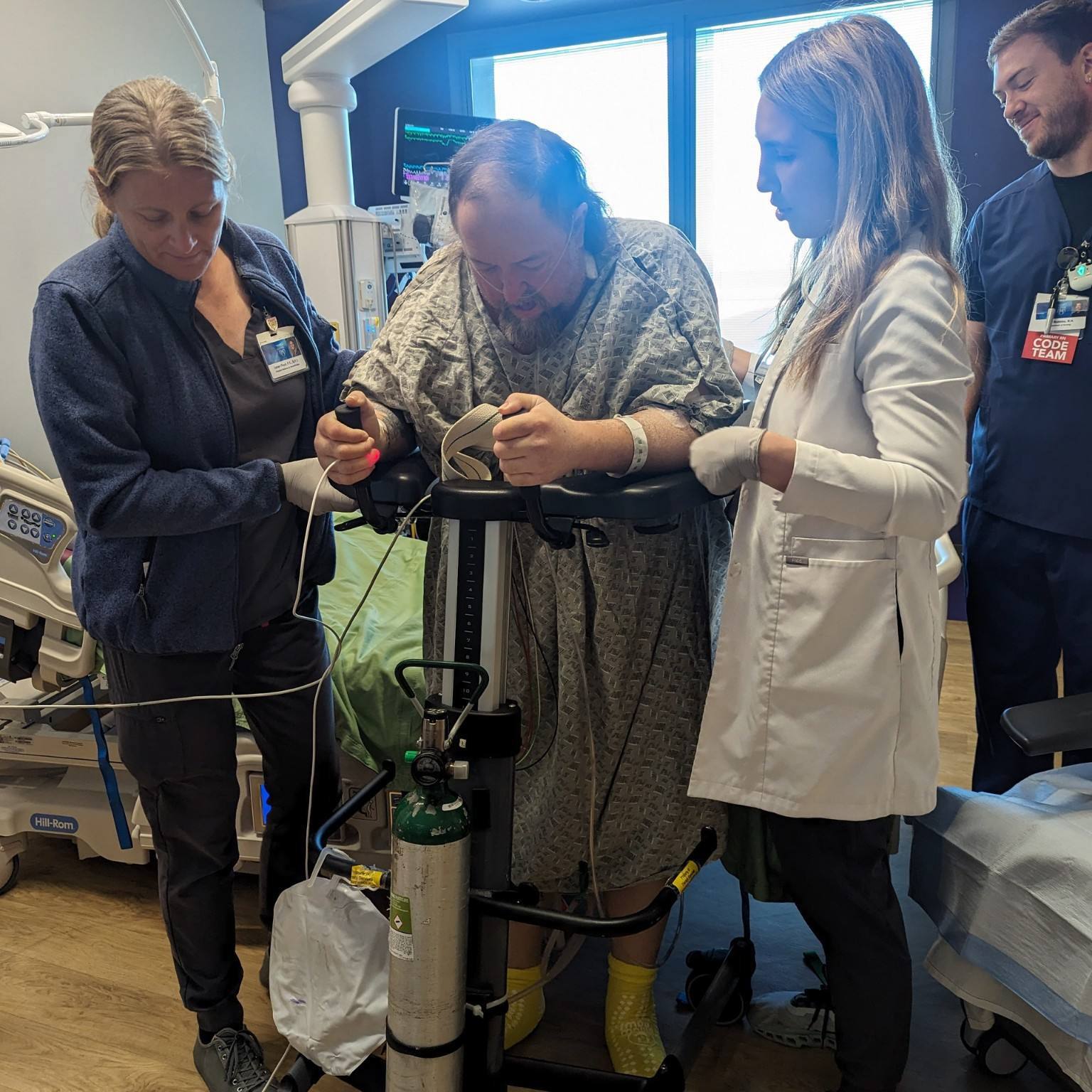

A few days later, Goodman followed up on his patient, expecting to find out that Snitzer had died. Instead, he had a room number at Saint Marys Hospital on Mayo Clinic’s Rochester campus. Goodman and the rest of the Mayo One crew visited Snitzer.

“I expected he’d be weak, sitting in his room,” says Goodman. “But he was sitting out in a visitor’s lounge with his brother. He stood up and greeted us when we came.”

That visit marked the first time Snitzer heard the remarkable story of his rescue. “I sat there with my jaw in my lap,” he says. “The first thing I said was, ‘Why didn’t you stop?’”

Dr. White says several factors contributed to the team’s persistence.

Tool to measure blood flow “The cardiac arrest was witnessed, and we knew that high-quality CPR had been started almost immediately after the event,” says Dr. White. “During the resuscitation, Mr. Snitzer was showing visible signs of life, including raising his arms. And we also had data that confirmed blood was flowing through his lungs to his brain.”

That data was supplied by a capnograph, an instrument that measures how much blood is flowing through the lungs and, thereby, to other organs. It’s frequently used to monitor patients in operating rooms, but is not commonly used by emergency personnel when treating cardiac arrest.

“The effort was successful in large part because of capnography, which informed us that if we persisted, it was conceivable we’d have a survivor on our hands,” says Dr. White. “This case shows the value of using real-time technology like capnography, which can confirm the effectiveness of CPR.”

It also demonstrates the value of CPR.

“The initial intervention was key to his survival, hands down,” says Goodman. “The equipment and interventions we as paramedics bring to the table are great, but we’d never have had a chance to use them if someone hadn’t been getting oxygen to Mr. Snitzer’s brain right away with CPR.”

Though he doesn’t relish the spotlight, Snitzer continues to tell his story as a way to help spread the word about CPR.

“After surviving this, I’m still trying to figure out what my purpose is,” he says. “I know I want to help whoever I can, and to do something meaningful. Hopefully telling my story will give a new jolt to CPR.”

Related Diseases

Related Departments

Related Articles