-

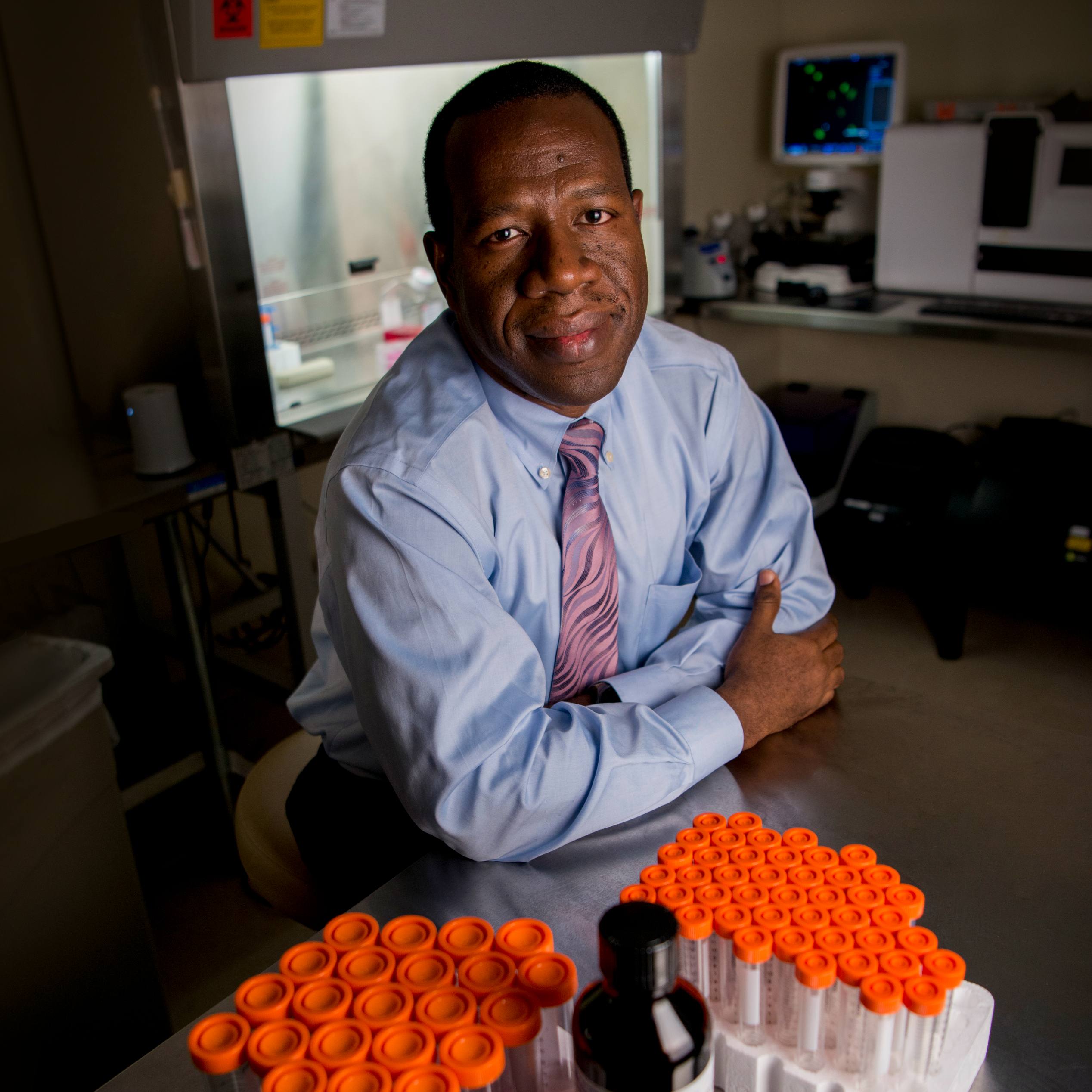

Dr. Fischer wants to improve the health of children everywhere

Philip (Phil) Fischer, M.D., says he’s always been interested in improving the health of children everywhere. He earned a diploma in tropical medicine and hygiene from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in England to enhance his ability to do so. He worked at a medical center in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo from 1985 to 1991.

Dr. Fischer has studied calcium and vitamin D deficiencies with rickets in Nigeria. His rickets research led to significant reductions in crippling bone disease in Nigeria, Bangladesh and other countries. His other research led to awareness of congenital malaria as a significant clinical problem in Africa, prevention and treatment of the disease in pregnant women, and improved child health.

In the last two decades while in the Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine at Mayo Clinic, Dr. Fischer also has focused attention on beriberi, a disease caused by vitamin B1, or thiamine, deficiency. Beriberi can affect metabolic,

neurologic, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal systems. The disease was largely eradicated in developed countries more than 70 years ago via dietary diversification and food fortification.

Dr. Fischer became aware of infants in Cambodia dying from what sounded like beriberi about 20 years ago when a nurse practitioner who lived in that country shared information when they met at conferences. She’d observed that

approximately 6% of babies in Cambodia died before their first birthday and that about half of those deaths seemed to be due to beriberi.

Dr. Fischer anticipates that the results will help prevent, diagnose and treat beriberi so the next generation of children will be healthier than the last.

“She was convinced that these babies had beriberi, and she saw them recover rapidly when she gave them injections of thiamine (vitamin B1),” says Dr. Fischer. “I had vague recollections of learning that thiamine deficiency causes beriberi, but I—along with most U.S.-trained pediatricians—assumed it was a problem for history books, not for babies in this century.”

Dr. Fischer and his colleague Mark Topazian, M.D., Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, visited Cambodia to see the phenomenon themselves. They designed a study that determined that children who appeared to have beriberi did indeed have a low blood level of thiamine. The study also revealed that seemingly healthy babies in the province also had low thiamine levels. All of the babies were thiamine-deficient. The team found that about two-thirds of infants hospitalized for breathing difficulties in another part of the country were thiamine deficient. But it was impossible to diagnose beriberi without a blood test, which wasn’t available in Southeast Asia in the early 2000s.

“We’d determined that thiamine deficiency was common in parts of Cambodia and that it was killing babies, but we didn’t know which of the sick babies would improve with thiamine,” says Dr. Fischer. “We had, however, learned that giving breastfeeding mothers oral thiamine supplements helped their babies get more thiamine. But there were no good systems to supplement at-risk mothers or fortify diets with thiamine. We were stymied about how to prevent beriberi at the population level.”

According to Dr. Fischer, thiamine deficiency is common in developing countries in babies of breastfeeding mothers who are thiamine-deprived, in large part, because a main staple of their diet is white rice. The thiamine in the husk of the rice is removed during processing.

In 2016, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation gathered physicians and scientists from around the world who were studying thiamine to help determine if thiamine deficiency deserved the foundation’s attention. Dr. Fischer was invited to participate in these meetings. As a result of the group’s findings, the Gates Foundation decided to invest in resolving thiamine deficiency and initiated projects including determining the extent of the problem around the world, how best to prevent it through fortification of foods, and how to choose and use blood tests to confirm it.

Dr. Fischer is part of a Gates Foundation-funded group determining how to diagnose thiamine deficiency in areas where thiamine blood tests aren’t available. This project is focused on a children’s hospital in Laos. Dr. Fischer has help from Mayo Clinic colleagues, including Casey Johnson, M.D., a resident in the Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, and medical student Kristin Cardiel Nunez, who has taken a year off from medical school to get a master’s degree.

Data collection for these projects ended in 2020, and Dr. Fischer anticipates that the results will help prevent, diagnose and treat beriberi so the next generation of children will be healthier than the last.

It’s been a 20-year journey, but we’re making progress. The scientific community is now aware that beriberi is a problem in other countries, and there is new awareness that beriberi also happens in North America.

Philip Fischer, M.D.

“We’ve learned that beriberi isn’t limited to Cambodia and Laos,” says Dr. Fischer. “We’ve teamed up with colleagues in India and Bhutan to find out what they’re seeing." Dr. Johnson has written a couple of review articles to educate medical professionals around the world about the problem of beriberi and solutions to thiamine deficiency.

“It’s been a 20-year journey, but we’re making progress. The scientific community is now aware that beriberi is a problem in other countries, and there is new awareness that beriberi also happens in North America. Within the next couple of years, we should have improved diagnostic methods and effective food-fortification strategies.”

In the meantime, in furtherance of his desire to help children around the world, Dr. Fischer has relocated to Sheikh Shakhbout Medical Center, a joint venture of Mayo Clinic and Abu Dhabi Health Services in the United Arab Emirates. He’ll serve as a pediatrician for at least three years and strive to impart the Mayo Model of Care to new colleagues in Abu Dhabi.

This article was originally published in Mayo Clinic's Alumni Magazine, Issue 2, 2021.