The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association announced new comprehensive guidelines for evaluating blood pressure Monday, November 13 that will drastically increase the number of Americans who have hypertension.

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association announced new comprehensive guidelines for evaluating blood pressure Monday, November 13 that will drastically increase the number of Americans who have hypertension.

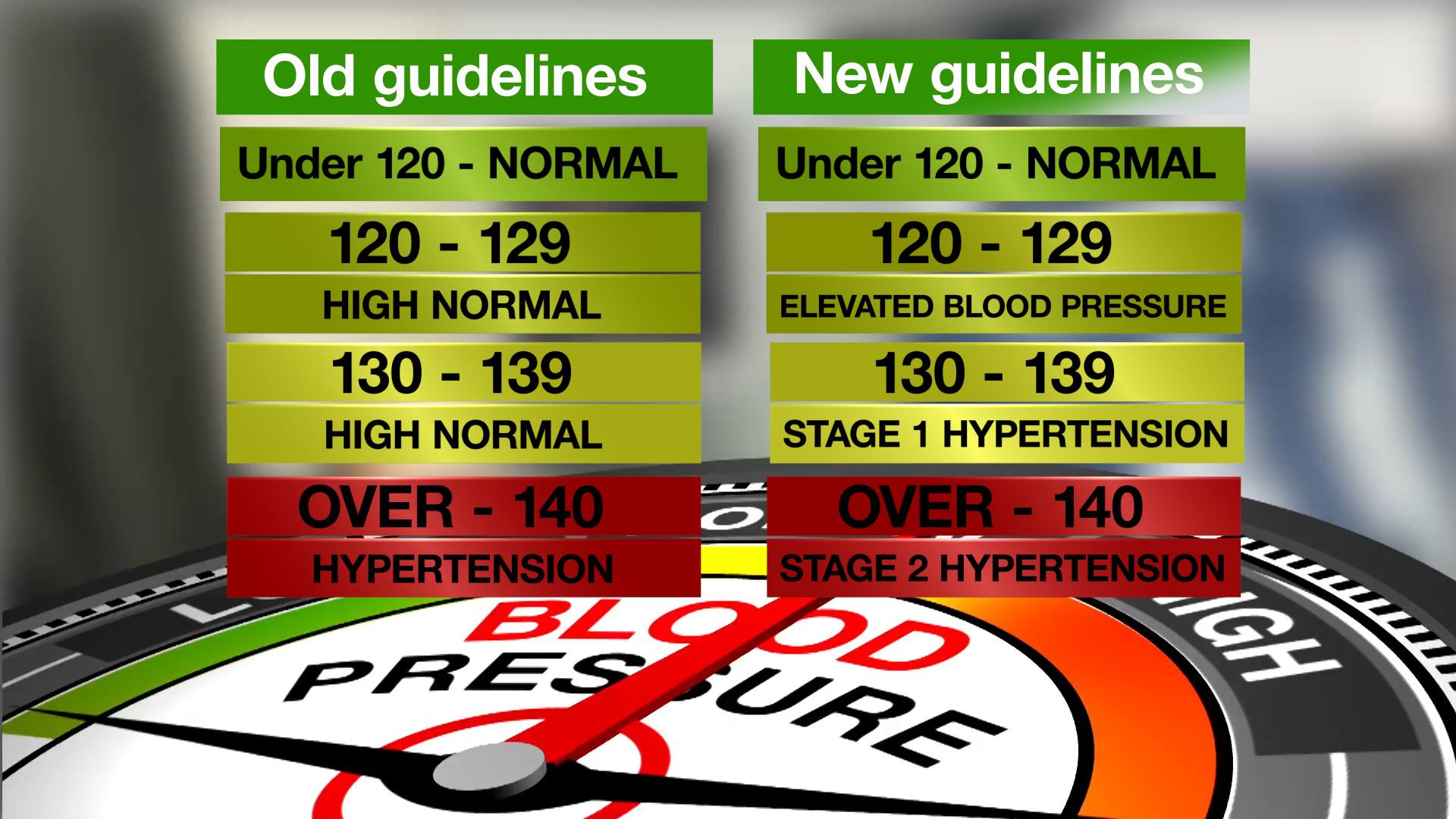

The committee that drafted the new guidelines lowered the blood pressure range of what is considered normal. That means people whose blood pressure used to be considered prehypertension, or high normal, will now be considered elevated blood pressure or stage 1 hypertension.

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association estimate that the change will affect more than 31 million Americans.

Watch: Dr. Sandra Taler discusses new blood pressure guidelines.

Journalists: Broadcast-quality sound bites and graphics are in the downloads.

Dr. Sandra Taler, a Mayo Clinic nephrologist, was a member of the Writing Committee that drafted the new guidelines. She says the committee took a data-driven approach based on recent studies to determine that it should lower target blood pressure figures.

“There are now enough studies to support lowering those targets and so the whole definition of high blood pressure has changed,” Dr. Taler says. “So, the change is above 120, and systolic – the systolic or the upper number is the key number that more of this is focused on – but 120 systolic and 80 diastolic would be the numbers that people want to know. If your blood pressure is at that level or lower, you have normal blood pressure.”

But the committee changed the guidelines when it comes to blood pressure levels above 120 systolic and 80 diastolic.

“The difference is if you’re between 120 and 129 and still 80 or lower on the bottom number but your upper number is 120 to 129, that’s now called elevated blood pressure,” Dr. Taler says. “It used to be high normal but still had the normal term in it. Now it’s elevated blood pressure. And so that will get people’s attention a little more that, hey, this isn’t normal.”

Dr. Taler says the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines will recommend people with elevated blood pressure begin making lifestyle changes, like exercising more, consuming less salt and consuming more potassium as part of an effort to lower their blood pressure.

But once people’s systolic blood pressure readings start reaching 130 and above, the new guidelines start calling for more drastic changes.

“The real difference starts at 130,” Dr. Taler says. “So, if you have a blood pressure of 130 to 139, that used to also be high normal (or prehypertension). Now, that’s stage 1 hypertension. So that is a change that’s really – you know, everyone always thought of 140 and 90, but now it’s 120 – well, 130 to 139 is stage 1 hypertension. So that’s going to be a big deal.”

But Dr. Taler says there is a little bit of nuance in this section of the new guidelines when it comes to how to treat people with stage 1 hypertension.

For those whose systolic blood pressure falls between 130 and 139, the committee is recommending health care providers evaluate a patient’s risk of cardiovascular events or death using an online risk calculator. The health care provider would plug numbers into the risk calculator representing the patient’s age, sex, blood pressure, cholesterol, whether they have diabetes, whether they smoke, and several other factors.

Based on how elevated the calculator shows the patient’s cardiovascular risk to be, health care providers will decide whether to prescribe the patient blood pressure-lowering medication or recommend they make lifestyle changes similar to those with elevated blood pressure.

“So if somebody has a blood pressure over 130 and over 80 and they have a cardiovascular risk that’s elevated – in that 10 percent or higher range – then, we would recommend they start medication at that stage 1 level,” Dr. Taler says. “If they don’t, if that risk is lower, then the recommendation will be lifestyle changes and so there will be more emphasis on starting those lifestyle changes and monitoring the blood pressure to see if it responds to those changes without necessarily going on medication.”

The new guidelines also change how systolic blood pressure readings of 140 and higher are classified.

“Then at 140 and higher and at 90 and higher, then it’s called stage 2,” Dr. Taler says. “Now, that used to be stage 1. So, people will say, oh, my – oh, my, you know, this is more severe and, so, that will be a more noticeable change as well, that 140 is now stage 2.”

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend patients who have stage 2 hypertension begin taking blood pressure-lowering medications in addition to lifestyle changes.

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association estimate that the changes in the guidelines will affect roughly 31.1 million Americans. Under the previous guidelines, 72.2 million people, or about 31.9 percent of the American adult population was classified as having hypertension.

Under the new guidelines, roughly 103.3 million people, or about 45.6 percent of American adults will have stage 1 or stage 2 hypertension. That’s an increase of 13.7 percent.

Dr. Taler says the previous comprehensive guidelines were released back in 2003. She thinks new and updated guidelines were overdue.

“Other groups have done guidelines but nothing comprehensive,” says Dr. Taler. “So first of all, this is the whole thing – everything from defining high blood pressure to how to evaluate, how to measure blood pressure, lifestyle changes that can help treat the blood pressure, lower it, drug therapy, how to choose drugs, what tests providers should do, all of that.”

Dr. Taler says past guidelines were based largely on observations and expert opinions. She says these new guidelines are based entirely on data from newer studies. The largest of those studies was a U.S. study called SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial), which was completed about two years ago.

“And the surprising finding in that study is – they randomized over 9,000 people to a blood pressure target of less than 140, which would be the standard at the time, or less than 120 millimeters mercury, which is quite a bit lower,” says Dr. Taler. “They found that the people in the lower target group had fewer cardiovascular events and a lower risk of dying and so that was really a big deal. And that changed the landscape so that we started to focus on, OK, we should be going lower.”

Using that conclusion, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Assocation committee based its guidelines on the idea that making efforts to lower blood pressure as soon as it started to rise above a systolic pressure level of 120, rather than waiting until Hypertension levels of 140 and above could greatly decrease the chances of people having cardiovascular events or dying.