Coughing. That is the sound that awoke Jennifer McDougal on the morning on Dec. 28, 2010. Her husband, Rodney, was in the bathroom preparing for work, and coughing. Suddenly, he collapsed.

Coughing. That is the sound that awoke Jennifer McDougal on the morning on Dec. 28, 2010. Her husband, Rodney, was in the bathroom preparing for work, and coughing. Suddenly, he collapsed.

Rodney, then 42, had a history of hypertension, so Jennifer immediately took his blood pressure. It measured 230/100 — dangerously high. “I didn’t know what was happening. One minute he was fine, the next he was out,” says Jennifer.

Paramedics transported McDougal to a local hospital near their home in Fleming Island, Fla., where medical staff determined he was suffering from an intraventricular stroke — a form of hemorrhagic stroke marked by a sudden bleed into the ventricular system of the brain, often as a result of hypertension. There is no drug to treat the condition, which accounts for about 5 or 6 percent of all brain strokes and is one of the most deadly.

Hearing the news, Jennifer was rightfully scared. “It never occurred to me he was having a stroke,” she says. What she didn’t know was that, McDougal, a self-described workaholic insurance broker by day and volunteer football coach by night, had neglected to refill his blood pressure medication. It was determined later that pressure buildup in his arteries caused one of the vessels to burst.

McDougal was airlifted to Mayo Clinic’s Comprehensive Stroke Center in Jacksonville, Fla., one of four centers in the southeastern United States participating in a national clinical trial to test the first potential treatment for this type of stroke.

Limited treatment options

With a hemorrhagic stroke, blood pools into the brain cavity. But, ultimately, a clot forms that causes additional oxygen deprivation, resulting in irreversible outcomes. “In the past, the only thing we’ve been able to do is stick a catheter in the brain to relieve the pressure and just wait for the clot to dissolve, but it often takes weeks,” says Mayo Clinic critical care neurologist William Freeman, M.D.

The CLEAR III study is comparing two clot-dissolving methods: treatment with a very small amount of the drug recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) vs. a saline irrigation method that “flushes out” blood clots.

“The drug tPA revolutionized the treatment of ischemic stroke, where a blood vessel supplying the brain becomes blocked,” says Dr. Freeman. “When administered within four hours after symptoms appear, tPA can minimize brain damage due to stroke. We hope to find out if tPA, if given within 72 hours of stroke onset, can also expedite recovery for hemorrhagic stroke patients and provide a better outcome.”

When Dr. Freeman shared the information about the study with Jennifer, she paused — but only momentarily. “I had to make a decision quickly because time was of an essence. But I knew how Rodney felt about studies. He had said once, ‘I don’t ever want to be on a trial.’”

Clinical trial offers hope

But, says Jennifer, her husband couldn’t foresee the dire choices in front of her. “I saw the condition my husband was in, and I had so much faith in Dr. Freeman as he explained this to me. This was life or death,” she says.

She agreed to the trial, and McDougal was treated with tPA. Hopeful, Jennifer gathered with the couple’s two children, friends and family. Within a few days, their prayers were answered as McDougal began responding to the therapy. When he awoke, however, he had no recollection of what had occurred.

“I woke up and saw all these get well cards and was trying to figure out where I was,” he says. “I didn’t know I was in the hospital or what happened.”

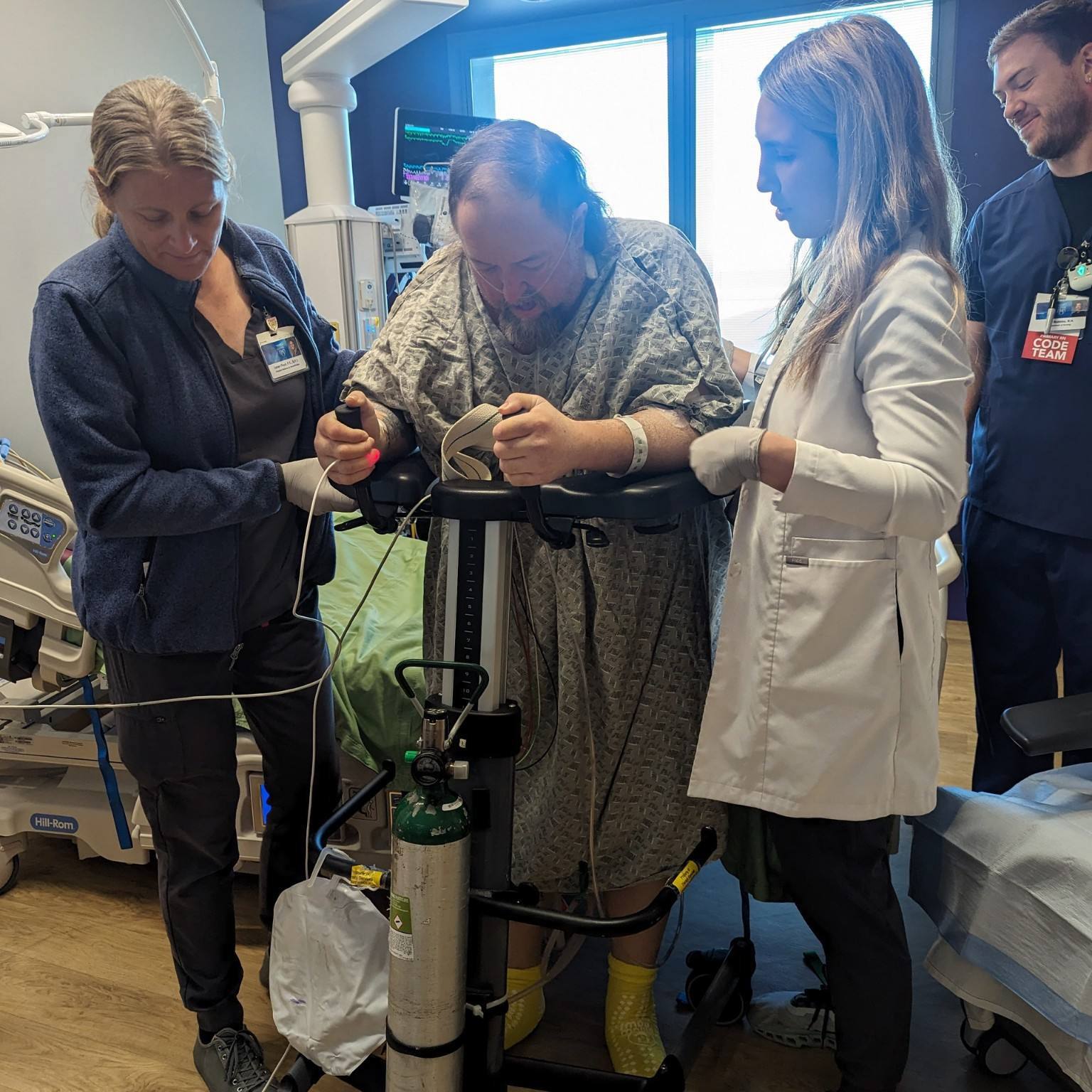

Doctors told Jennifer that as a result of the stroke, McDougal could be paralyzed, have speech problems or trouble walking. Today, more than a year later, he still has no memory of the stroke, but no other complications. “I’m feeling great. No problems, no side effects,” he says. His wife notes one change, though. “He’s calmer now,” says Jennifer. And he is more diligent about his medication, too.

“Of course, I text him, I call him, our daughter calls him, we always remind him,” says Jennifer.

And McDougal now embraces the opportunity to talk about research and clinical studies. “I never understood what research and trials were all about until now,” he says. “I am so thankful that this opportunity was offered to us. I definitely recommend research and trials because it’s an opportunity to not only get the help needed but also down the road could help save someone else’s life.”

Dr. Freeman continues to be amazed by McDougal’s recovery and says he is hopeful about the future of the tPA therapy. Preliminary study data is positive, with death rates declining. “If the CLEAR study continues to show significant improvement in patient outcomes, it could transform the future care of intraventricular hemorrhagic stroke care the same way tPA changed ischemic stroke therapy in the 1990s,” he says.

The article comes from our Sharing Mayo Clinic print publication.

Related Diseases

Related Departments

Related Articles