-

Discovery’s Edge: Eyes gone bad

A clinician teams up with basic scientists to learn how toxic RNA short-circuits corneal cells

The eye’s outermost tissue, the cornea, is a bit more substantial than you might imagine. It’s made up of lots of types of cells and structural proteins, arranged in highly organized layers. At about 560 µm (1/45 of an inch), the cornea is transparent, but about as thick and bendy as a credit card. For clear vision, it must be free of cloudy areas, but disorders can roll over it like a storm — the most common being an inherited, degenerative disease called Fuchs' corneal dystrophy. Fuchs' (pronounced “fooks”) affects almost five percent of middle-aged patients with some variance across ethnicities. Most people remain symptom free, but many lose their vision altogether; Fuchs' accounts for more than 14,000 corneal transplantations in the U.S. annually.

On Mayo Clinic’s Rochester, Minn. campus, surgeon Keith Baratz, M.D., meets and treats Fuchs' patients almost every day. The disease slowly kills off the cells responsible for regulating the amount of fluid entering the cornea. As the cells die, the first symptom patients usually notice is blurred morning vision. This happens because when their eyes are shut as they sleep, fluid builds up in the cornea, causing it to swell. While their eyes are open over the course of the day, the excess fluid evaporates, so they usually see better by evening. But as the disease advances, the periods of swelling, impaired vision and pain last longer.

Currently, there is no treatment for Fuchs' other than transplant surgery for late-stage patients. Dr. Baratz wants to change that. He is working with two Mayo Clinic investigators — Michael Fautsch, Ph.D. and Eric Wieben, Ph.D. — to learn how the disease manifests. All three have embraced the problem passionately. “[Fuchs'] impacts reading and driving, then it gets harder to tell your knife from your fork, and to recognize the people you love,” explains Dr. Fautsch. Together these three researchers are clearing the way to controlling disease progression, and perhaps to preventing it altogether.

Currently, there is no treatment for Fuchs' other than transplant surgery for late-stage patients. Dr. Baratz wants to change that. He is working with two Mayo Clinic investigators — Michael Fautsch, Ph.D. and Eric Wieben, Ph.D. — to learn how the disease manifests. All three have embraced the problem passionately. “[Fuchs'] impacts reading and driving, then it gets harder to tell your knife from your fork, and to recognize the people you love,” explains Dr. Fautsch. Together these three researchers are clearing the way to controlling disease progression, and perhaps to preventing it altogether.

Finding the gene, building the team

It has long been clear that Fuchs' is an inherited disease. Typically, if you have it, and one of your parents had it, each of your children has about a 50-50 chance of being affected. Even so, the genetic basis for the majority of cases remained a mystery until about five years ago when Dr. Baratz began to compare the DNA of people who did and didn’t have the disease.

A gene is basically a stretch of molecules called nucleotides that code for a protein. Different versions of the same gene are called alleles. People inherit two alleles for most of their genes, one from each parent. Sometimes a single nucleotide — A, T, C or G — differs between people; this is called a single nucleotide polymorphism or SNP (pronounced “snip”).

In 2010, working together with Albert Edwards, M.D., Ph.D. (who was then at Mayo Clinic and is now in private practice in Eugene, Oregon), Dr. Baratz came across a SNP that was several times more common in his Fuchs' patients than in people without the disease. This SNP was located to a gene called transcription factor 4 (TCF4). (Transcription factors provide instructions for making proteins that, by binding to specific regions of DNA, help control the activity of other genes.) Drs. Baratz and Edwards were the first to identify TCF4 as the major contributor to adult-onset Fuchs' in most families. Their discovery began a flurry of new research worldwide, and provided a genetic marker that can be used to identify individuals with the disease.

As exciting as this result was, Dr. Baratz wanted to learn more; it is one thing to know what gene is affected, but quite another to figure out how the defect causes disease. So he took his results across the Rochester campus to Dr. Eric Wieben, head of the Medical Genome Facility - the part of Mayo's Center for Individualized Medicine that gives investigators access the latest genomics technologies.

"Eric's the main guy. I never expected that he'd take an interest," said Dr. Baratz.

"It was five years ago yesterday when Keith first showed up in my office," said Dr. Wieben. "His story was unusual in a couple of ways. Most genetic diseases are incredibly rare — this one's incredibly common. And the strength of his [result] was pretty much unheard of."

Genetic diseases vary in incidence across the globe and by ethnic group, and most affect only one person in thousands or even millions. Fuchs' is a couple of orders of magnitude more common, with about five out of every hundred Caucasians experiencing symptoms by midlife.

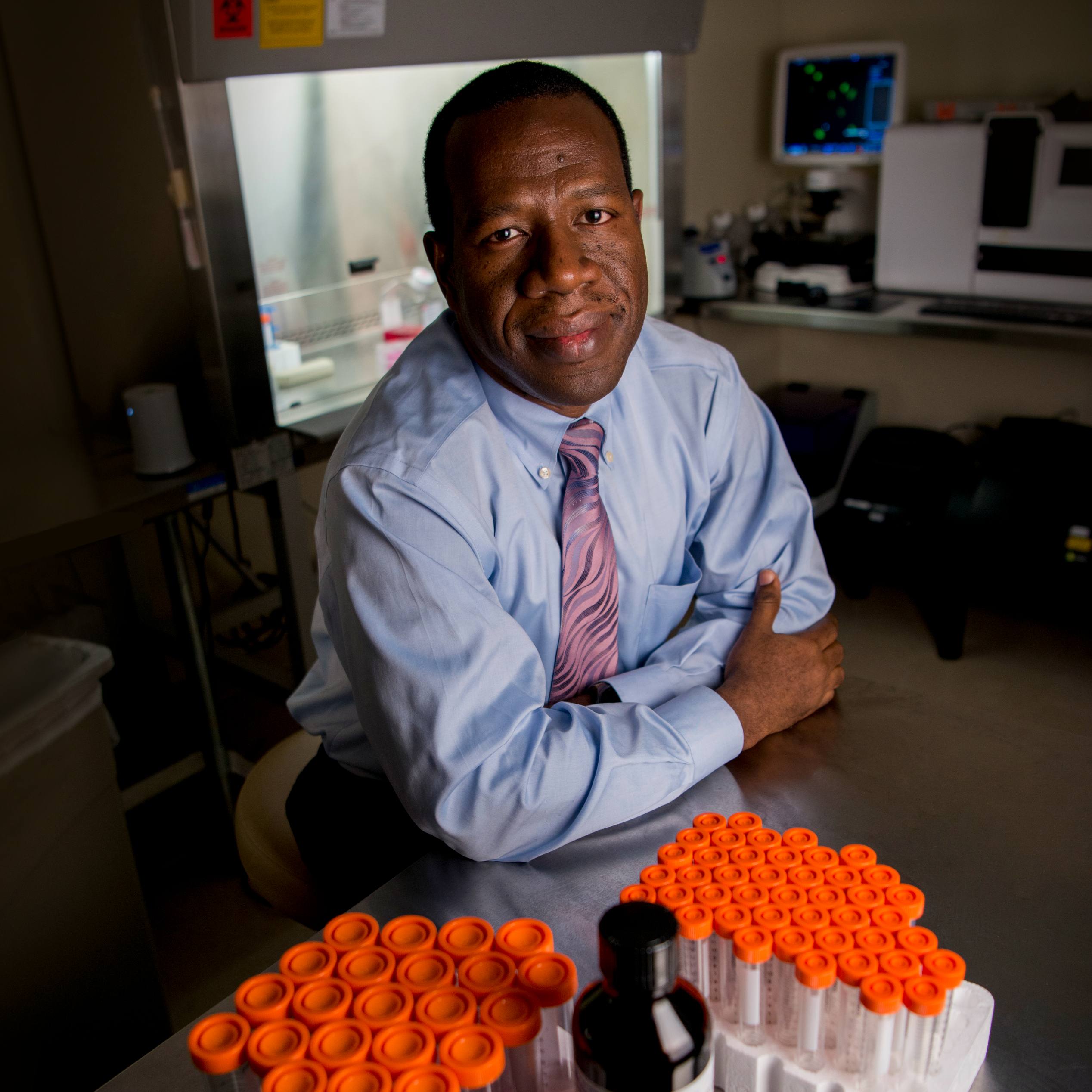

Needless to say, Dr. Wieben was all in, and the two decided that a third member was needed on their team — Dr. Mike Fautsch, who had been Wieben’s graduate student many years ago, now brought another area of expertise to the table. “I do the molecule-based assays, and Mike does the cell-based assays; Keith has the samples and we have the technology to test them," explained Dr. Wieben.

Under the microscope: why corneal cells?

“I got involved,” continued Dr. Fautsch, who specializes in studying eye tissues and cells in culture in his laboratory, “because I could go a step beyond the genetic data by looking at cells from normal and from Fuchs' patients. One of the things we want to understand is, why is this mutation affecting only the corneal cells and not the other cells in the body?”

The answer, he says, may be oxidative stress — the burden placed on the cells of our bodies by the constant production of free radicals, which are made during the normal course of metabolism and as a result of other pressures that the environment brings to bear. In this case, that pressure is the ultraviolet radiation hitting your corneas during, say, an afternoon sledding with the children, or a chat over the hedge with your neighbor. (Another reason to wear a wide-brimmed hat during the bright hours of the day, even in winter.)

UV exposure is a well-understood environmental stress factor that generates free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are harmful to cells. Since the cornea is the first target of UV-light entering the eye, it is especially susceptible to damage from ROS. It is not only exposed regularly to sunlight, but also to atmospheric oxygen, mainly dioxygen, which produces ROS.

The cornea makes its own antioxidants to scavenge reactive oxygen, but certain diseases — including Fuchs' — are marked by increased levels of oxidative stress markers, indicating that oxidative stress may play an important role in their development and progression.

Toxic RNA

By 2012 Drs. Baratz and Wieben had pinpointed the Fuchs' mutation to an intron (a noncoding section of DNA that’s spliced out before a gene is translated into a protein) within the TCF4 gene (PLoS One). Typically, a mutation in an intron can keep a gene from being transcribed at all, or it can dramatically change the protein that’s made. In this case, the change is a set of three nucleotides (specifically, CTG) that’s reiterated (CTG CTG CTG etc). This is called a trinucleotide repeat. If a gene has only a few repeats, its DNA can usually still be copied accurately, but when there are a lot of them, problems occur. Generally, the larger the expansion, the more liable it is to cause disease and to increase disease severity through generations in a family.

The trinucleotide repeat expansion in TCF4 that they found turned out to be the specific genetic defect that leads to adult-onset Fuchs' in most families. In a healthy person, there may be 15-25 CTG repeats in TCF4, whereas in a person with Fuchs', there may be ten to 100 times that many (i.e. 2000 repeats). That's a devastating change.

Drs. Baratz and Wieben now also work closely with Joel Gottesfeld, Ph.D., a senior investigator at Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, who saw their publication about the three base-pair expansion and became intensely interested, given that he'd been studying neurological and neuromuscular diseases caused by similar repeat expansions (e.g. Friedreich’s ataxia, myotonic dystrophy and Huntington’s disease). In 2015, Drs. Wieben, Baratz, Gottesfeld and their research teams published results (J. Biol. Chem.) demonstrating that the expansion in TCF4 creates a problem called RNA toxicity. Normally, the RNA transcripts of the TCF4 gene are meant to deliver a message from the gene in the cell’s nucleus to the protein expression system in its cytoplasm. But the RNA copies (transcripts) of the bad DNA are so long that the cellular machinery doesn’t recognize them and transport them like it’s supposed to. Instead, the transcripts are bound up by proteins to form little chunky obstructions called RNA foci that stay in the nucleus, eventually mucking up the expression of other genes as well.

In Dr. Fautsch’s corneal cell cultures, he can actually stain for and see these RNA foci, and test for conditions that accelerate or decelerate their formation. Drs. Gottesfeld and Fautsch are developing a continuous cell line for cell-based assays, making it easier to study Fuchs' and to test drug candidates in the laboratory. One of their goals is to find a drug that may be able to slow disease progression and improve patients’ quality of life. They are also looking at aspects of regenerative medicine, including stem cell therapy, that might eventually be able to stop progression altogether.

Through the Medical Genome Facility, Dr. Wieben is testing large libraries of biological molecules to understand the differences between Fuchs' and healthy corneal cells by checking out where, when and at what level different genes are being expressed and proteins made. He’s generating millions of data points and collaborating with a virtual army of biostatisticians to help make sense of them.

Tuesday morning coffee club

Dr. Baratz, Fautsch and Wieben meet almost weekly. "It's how we start our Tuesday mornings," explained Dr Wieben. "We discuss progress and holdups, and what things to push." They also decide together where the corneal samples provided by Dr. Baratz's patients will go — to Dr. Fautsch's laboratory to develop cell lines to study the physiology of Fuchs and to test drug candidates, to Dr. Gottesfeld's laboratory to feed into the development of stem cell therapy, or to Dr. Wieben's facility for gene expression profiling. "It's the most fun I've had in the 32 years I've been at Mayo, working on this project," says Wieben.

“It’s a collaboration between a clinician and basic scientists,” explains Dr. Fautsch, “the kind of success story Mayo prides itself on.”

When this all began, explains Dr. Baratz, "I wasn't all that interested in genetics. But now I want to figure it out to the end, all the way through the biochemical pathways and then to realistic options to treat patients."

For Dr. Baratz, it starts and ends with his relationship with patients. "I'm their Doc," he says.

- Megan McKenzie, November 2016