-

Featured News

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Primary sclerosing cholangitis

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: What causes primary sclerosing cholangitis? How long does it take for it to progress?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: What causes primary sclerosing cholangitis? How long does it take for it to progress?

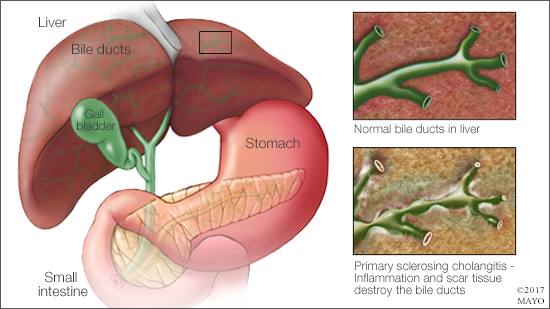

ANSWER: Primary sclerosing cholangitis, or PSC, is a chronic inflammatory disease of the bile ducts that may lead to severe liver damage and liver failure. PSC also can be associated with an increased risk of cancers in the liver, gallbladder, bile ducts and colon. The length of time it takes for the disease to progress can vary significantly. Unfortunately, there’s currently no effective medical therapy for PSC. Many people with end-stage liver disease due to PSC are considered for a liver transplant.

Bile ducts are the structures through which bile flows from the liver to the intestines. Bile helps the body absorb nutrients and other elements from food, and helps maintain the nutritional balance within the body. With PSC, “cholangitis” refers to inflammation of the bile ducts. “Sclerosing” describes the hardening and scarring of the bile ducts resulting from chronic inflammation.

The structure of the bile ducts resembles a tree. A single bile duct outside the liver connects to the small intestine. That duct branches into two main ducts (left and right hepatic ducts). From those two ducts, a series of branches form. Those branches become smaller and smaller as they go farther into the liver. PSC can affect small, medium or large bile ducts.

The cause of PSC is unclear. A combination of genetic predisposition and immune system factors could be involved. The immune system reaction associated with PSC may be triggered by exposure to one or more substances in a person’s environment in people who are genetically predisposed to the disease. People who have inflammatory bowel disease are susceptible to developing PSC.

Signs and symptoms of advanced PSC include yellowing of the eyes or skin (jaundice), itching, abdominal pain, leg swelling and infection. Today, the disease often is caught before these symptoms appear, based on results from routine blood tests that may suggest liver problems. A special imaging exam of the bile ducts, called a cholangiography, typically is used to definitively diagnose PSC. Inflammatory bowel disease, which can be asymptomatic, is present in 70 to 80 percent of patients with PSC. Therefore, a colonoscopy is recommended after diagnosing PSC to screen for inflammatory bowel disease. The most common symptom of inflammatory bowel disease is diarrhea.

There is no medical treatment that can slow the progression of PSC. Instead, treatment focuses on decreasing symptoms using a combination of medical therapies and procedures. For example, itching can be treated with various medications, such as oral powders that bind to bile in the intestines. Balloon dilation and stent placement using specialized endoscopic procedures may be used to open blockages in the larger bile ducts. Periodic pictures of the liver and blood tests to screen for tumors of the liver, gallbladder or bile ducts may be recommended to detect such complications early. Similarly, if inflammatory bowel disease is present, annual colonoscopies typically are recommended to screen for any precancerous or cancerous colon lesions.

Lifestyle changes can help manage PSC, too. Avoiding alcohol; quitting smoking; maintaining a healthy weight; eating a healthy diet that includes fruits, vegetables and whole grains; and getting vaccinated against hepatitis A and hepatitis B may help preserve liver function.

Some people with PSC progress and need a transplant soon after diagnosis. However, many carry the disease for decades without it showing any significant progression or symptoms. People with end-stage liver disease or a select group of individuals with early-stage bile duct tumors may benefit from a liver transplant. However, the average length of time from a PSC diagnosis to needing a transplant is 21 years. Most individuals with PSC do not develop bile duct tumors. And only a subset of patients will require a transplant. Development of effective medical therapies, improved techniques to detect disease related complications, and methods to better predict outcomes are key areas under active investigation. — Dr. John Eaton, Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota