-

Research

Growing mini-organs to find new treatments for complex disease

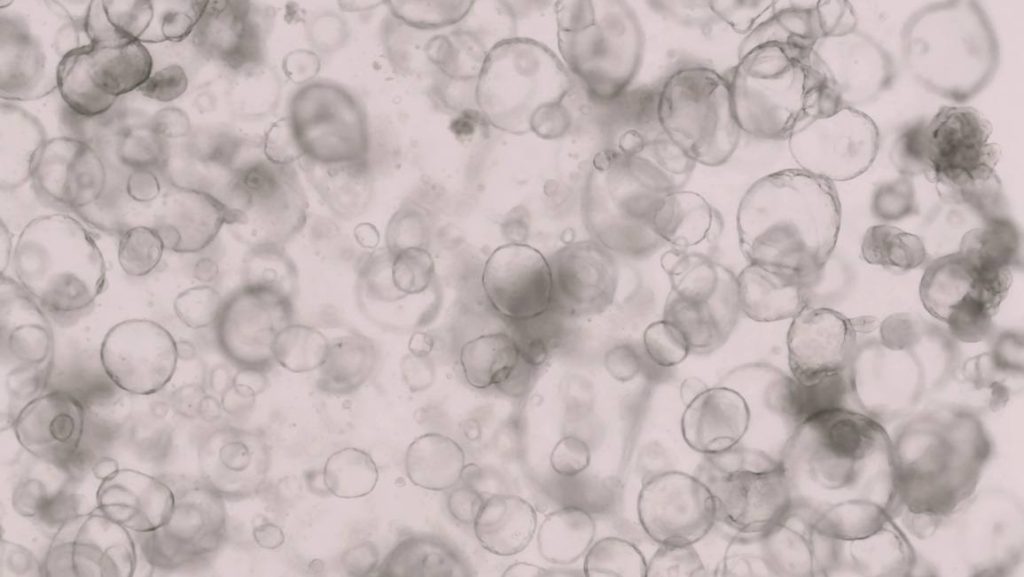

Mayo Clinic investigators are growing three-dimensional human intestines in a dish to track disease and find new cures for complex conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease. These mini organs function like human intestines with the ability to process metabolites that convert food into energy on a cellular level and secrete mucus that protects against bacteria. These 3D mini intestines in a dish, known as "organoids," provide a unique platform for studying the intricacies of the human gut.

Cells that cluster into the 3D intestinal organoids are grown from a small amount of human intestinal tissue containing epithelial stem cells, taken from a person via a biopsy or surgery. Epithelial cells provide a protective barrier on skin, glands and internal organs and have shown potential for healing and regeneration. Brooke Druliner, Ph.D., leads this team science research.

Charles Howe, Ph.D., directs the Office of Core Shared Services and is working with Dr. Druliner and others across the Mayo Clinic to build the infrastructure in support of organoid-based research and translation.

"Thanks to these advancements, we are closer than ever to being able to create a "patient-in-a-dish" platform," he says. "Intestines in a dish are an example of how this new research tool will help us better understand inflammatory reactions in gastrointestinal-tract diseases. Our hope is this could lead to new drug targets and treatments."

A growing health problem

Inflammatory bowel disease is a growing worldwide health problem that affects approximately 3 million people in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control. It encompasses a group of inflammatory conditions that affect the digestive system such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease include abdominal pain and diarrhea but vary widely from one person to the next, posing a challenge in finding successful treatments. Immunotherapies are commonly prescribed but are effective only 40% of the time, and few patients experience lasting relief.

Intestinal organoids provide a new, humanlike tool for tracking inflammatory bowel disease.

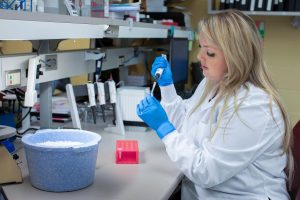

"A combination of animal and human models is more effective for our research. Intestinal organoids have the potential to allow us to screen drugs for toxicity and monitor effectiveness before the drug is tested in a clinical trial," says Dr. Druliner.

A Mayo Clinic research team including Dr. Druliner and William Faubion, Jr., M.D., a gastroenterologist-researcher and medical director for Mayo Clinic's Center for Regenerative Biotherapeutics, is using these intestinal organoids to recreate features of inflammatory bowel disease.

Their robust research with intestinal organoids is bolstered in part by the more than 4,000 patients that come to Mayo Clinic every year with inflammatory bowel disease. Consenting patients donate tissue to a specialized biobank, and that tissue is matched with immune cells from the same patient. Those tissues and cells are used to create individualized 3D mini-intestines, with the goal of using these models for testing therapies tailored to the specific patient's individual disease.

"Our goal is to use our models to identify inflammatory bowel disease subtypes with predictable outcomes, including response to therapy or risk of disease progression," says Dr. Druliner.

Revolutionizing research

The broader vision is to one day expand 3D organoids from a variety of organs, preserve them and use them to track disease and screen drugs for a wide range of conditions including cancer, epilepsy, heart disease and dementia.

"We think this has the potential to revolutionize the way we approach disease research. We hope to save time and resources and avoid development of therapies that fail upon translation into patients," says Dr. Howe. "Understanding which treatments show potential for success in human organoids could dramatically accelerate the rate of new therapies for patients with unmet needs."

A long-term goal would be to not only use the intestinal organoids for drug identification but also as a source of tissue regeneration to heal disease.

The researchers have partnered with the Center for Regenerative Biotherapeutics to discuss the potential for biomanufacturing these mini organs in the future and how to establish quality control, reproducibility and scalability.

Challenges to overcome

The organoid research team already has overcome many challenges, including understanding ways to identify and collect fresh tissue to grow the organoids, and how to test if they accurately mimic the function of their original organ. Researchers are currently trying to address issues of quality control and validation to ensure the mini organs are accurate representations of a patient's individual disease. Another goal is to include more diverse cells such as immune cells, neurons or vasculature cells in these mini organs.

This research was initially made possible by Mayo Clinic's Cells2Cures initiative and Mayo Clinic’s Center for Regenerative Biotherapeutics. It is now funded in part by an Organoid Biomanufacturing for Transforming Healthcare grant from the Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics, which is working towards establishing a joint Mayo Clinic – University of Minnesota Organoid Center. Learn more about this grant and the principal investigators from the University of Minnesota on the Minnesota Partnership website.

Related resources:

- Mayo Clinic ‘mini-brain’ study reveals possible key link to autism spectrum disorder

- Minnesota Partnership awards five collaborative research grants for 2023