This year's World AIDS Day will be commemorated on Dec. 1. It was 40 years ago in June that the first scientific report was made describing pneumocystis pneumonia, which later became known as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). The AIDS epidemic has claimed more than 36 million lives since the first cases were reported in 1981. AIDS is a chronic, potentially life-threatening condition caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). While more people can live with the virus that causes AIDS, there is no cure.

One question some have is how vaccines for COVID-19 were developed within two years while a vaccine for HIV remains unavailable. Dr. Andrew Badley, director of the HIV Immunology Laboratory at Mayo Clinic, says when it comes to HIV/AIDS, there are different challenges, including a myriad of mutations of HIV.

Watch: Dr. Andrew Badley talks about the impact of HIV research.

Journalists: Broadcast-quality sound bites with Dr. Badley are in the downloads at the end of the post. Please courtesy: "Andrew Badley, M.D. / Infectious Diseases/ Mayo Clinic."

"There are really two kinds of vaccines that we can talk about. One is a vaccine to prevent infection. Because HIV can infect cells through multiple different receptors, no vaccine has yet proven successful in preventing infections in humans. The other kind of vaccine is designed to treat the infection. In the setting of treating infection, because HIV targets the same immune cells that respond to the vaccine, by the time you get an infection, it wipes out your ability to respond to that vaccine. Also, the second challenge for a therapeutic vaccine is that like every virus including SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), the virus evolves over time. And in the world of HIV, countless different strains of HIV are floating around within an individual patient. So far, we've been unable to come up with a vaccine that is protective against all of them. That's why a therapeutic vaccine doesn't work today," Dr. Badley says.

The advances in the four decades of HIV/AIDS research enabled progress in COVID-19 research, including developing a vaccine, says Dr. Badley.

"The successes we've seen in the SARS CoV-2 pandemic are driven in a very large part by the decades of funding and decades of research that went into HIV. That includes how to make drugs, how to make vaccines, how to treat virus infections, how to monitor virus infections. All of those advances were made because of HIV research, and we're reaping the rewards ― both in HIV, which is a very treatable disease today, but also in terms of SARS CoV-2 in the pandemic."

Mayo Clinic HIV research

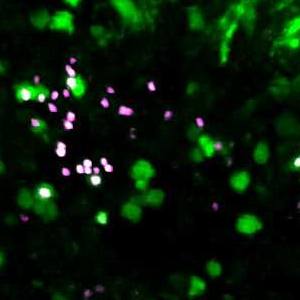

One of the research projects led by Dr. Badley uses the prime, shock and kill approach to cure HIV infection.

"Our approach to HIV has been first to study how it is that HIV kills the cells that it does kill. And we've spent years doing that, and we have some pretty good ideas on how that happens. Now we're trying to make it so that when HIV infects a cell, it kills every cell that it infects. And if we are successful then what has been accomplished is that we will have converted HIV into an influenza-like infection. We have developed a variety of pharmacologic approaches using drugs that are typically in the cancer arena to try to augment the death of those infected cells. We have two approaches to doing that. One is to use a drug that's used for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. It is a drug that blocks an anti-death protein. We know that when we infect cells with HIV in the presence of that drug, more cells die. We've shown that in a test tube, using cells from HIV infected patients. More recently we are using that same drug in animal model experiments and we ho[pe to finish and publish those experiments soon."

Another approach they have is with a drug that's used to treat multiple myeloma.

"It is a drug that blocks a pathway called the proteasome. And the proteasome is very important for a lot of the proteins involved in HIV replication, and in the survival of HIV-infected cells," says Dr. Badley. "We've shown in a test tube that this treatment causes more of the infected cells to die."

Dr. Badley says his team has completed a clinical trial on this approach in HIV-infected patients.

"We know that it's safe and well-tolerated, and the changes in the amount of virus-infected cells is reduced compared to historical cohorts. Now we hope to move toward a comparative trial where we see if it does something beneficial, compared to standard therapy alone."

While a vaccine for HIV/AIDS remains challenging, Dr. Badley is optimistic that HIV will one day be cured.

"I'm hopeful that these approaches will work," says Dr. Badley, "And very optimistic that HIV might be cured. And by cured, I mean HIV-infected patients no longer need to take pills to suppress the virus, and HIV is either gone or functionally gone from the body. Multiple groups around the world are working on multiple different approaches. Ours is one of them. I think that the final answer will be combining several of these approaches at the same time, and one day, we'll get to a functional cure or eradication of HIV."

Read more:

- Forty years of HIV/AIDS: Will the epidemic end?

- What people living with HIV need to know about COVID-19.

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Why you should be tested for HIV.

________________________________

For the safety of its patients, staff and visitors, Mayo Clinic has strict masking policies in place. Anyone shown without a mask was recorded prior to COVID-19 or recorded in an area not designated for patient care, where social distancing and other safety protocols were followed.