-

Science Saturday: The art and science of never giving up

In March 2020, at the start of the pandemic, Anya Magnuson's own health was in crisis. The 21-year-old Minnesotan had already endured four brain surgeries, 35 lumbar punctures and about 11 weeks of hospitalization. At various times during the preceding 28 months, she was treated for fungal meningitis, an inflammatory disease known as neurosarcoidosis, and finally a rare blood cancer called Erdheim-Chester disease.

None of the treatments her doctors had prescribed worked; in many cases, they made her condition worse. Her vision was failing. She lost feeling in her feet and could no longer walk. Her headaches were so brutal that after one 13-hour episode of vomiting and writhing in pain, she cried out, "Why can't anyone fix me?"

Ronald Go, M.D., a Mayo Clinic hematologist, and Jithma Abeykoon, M.D., a Mayo Clinic hematology-oncology fellow, two members of the large, interdisciplinary team treating Anya, began to question her diagnosis of Erdheim-Chester disease. They wondered whether they should biopsy her spinal cord again. A neurologist consulting on the case thought it would be too risky to perform the procedure in her current state.

While they debated the next steps, the world outside was shutting down. Within Mayo, only surgeries deemed to be "emergency" or "lifesaving" were permitted. Her case was a mystery, and it wasn't clear if a biopsy would provide any answers or just cause more pain.

"It was a really dark time," says Colleen Kelly, Anya's mother.

The early days

Anya is exceptional. In high school, she was a National Merit Scholar, editor of her yearbook and an all-conference volleyball player. She became fluent in Spanish while working alongside international students at a Twin Cities amusement park, eventually testing out of four semesters of the subject.

"She was very driven academically but driven to the beat of her own drum," says Colleen.

The headaches began in November 2017 during her second year at Arizona State University in Phoenix. She felt like her head was going to explode. She went to the emergency department, but her symptoms were dismissed as migraines. Her next symptom emerged in early December while she was home for the holidays. She told her mom that her hand was in the wrong place.

"That's when I knew something more serious was wrong," says Colleen.

The next night Colleen stayed up late, "madly" Googling Anya's symptoms: headaches, blind spots, numbness. It was right after "idiopathic intercranial hypertension" — unexplained high pressure around the brain — came up in her search results that she heard her daughter trip and fall upstairs. She took her to the hospital right away.

Anya spent three weeks in and out of the hospital, making little to no progress. But then she started seeing Johanna Beebe, M.D., a neuro-ophthalmologist who had done her residency at Mayo Clinic.

"We still consider her to be the first person who basically saved Anya's life," says Colleen.

Dr. Beebe spent the Friday afternoon before Christmas writing up Anya's entire medical record and calling her old mentor in the hope of getting Anya admitted to Mayo Clinic.

Her safe space

At Mayo, it was another three weeks of testing to try to figure out what was going on. At that point, the doctors charged with her care still didn't have answers, but they knew they had to do something to relieve the dangerously high pressure on Anya's brain.

In January 2018, they inserted a shunt and performed a craniotomy and brain biopsy, which was inconclusive. With little else to go on, they presumed that she had fungal meningitis and put her on the potent antifungal medication amphotericin.

During the months that followed, Anya endured an infection, emergency surgery, a different shunt, and another brain surgery. Yet she pushed on, traveling to Oklahoma for a photojournalism internship; Phoenix to resume her studies at Arizona State University; and Lima, Peru, for a reporting trip. By the time she returned home from college in May 2019, she had developed another new symptom: numbness in her feet and toes, making it hard to walk. Eoin Flanagan, M.B., B.Ch., a Mayo Clinic neurologist, suspected neurosarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease that affects the nervous system. But positron emission tomography scans revealed strange dark masses along her lower spine.

"It was horrifying," says Colleen. "You do not need to be a doctor to see it and think: Oh my God, that's awful. Whatever that is, it is not good."

The doctors biopsied one of those masses and sent its DNA for sequencing. Though the sequencing wasn't informative, the biopsy itself was. Anya's tumors were chocked full of white blood cells known as histiocytes, a hallmark of Erdheim-Chester disease.

The finding was a surprise. Erdheim-Chester disease typically affects middle-aged men. Even then, it is exceedingly rare. Less than 2,000 cases had ever been reported. Dr. Go said in his 13 years as a community hematologist-oncologist, he had not seen a single case. Until Anya.

The doctors prescribed the off-label use of a targeted drug called cobimetinib, which had been shown to help some patients with Erdheim-Chester disease. However, in Anya's case, it was ineffective and came with debilitating side effects. Next, they tried the immunotherapy drug interferon to stimulate her body to fight the cancer. That backfired, sending her into a downward spiral.

Her headaches became so excruciating she had to leave school. Colleen flew to Arizona to get her, bringing her home in a wheelchair with a gallon-size bag of pain medications in her purse. Back at Mayo, they tried six rounds of the chemotherapy drug methotrexate. The side effects were manageable, but her disease kept progressing.

Through it all, Colleen says she and Anya considered Mayo to be her safe space.

"Even when things were really bad, every time I drove her down there, I thought: 'She's at Mayo. It's going to be OK because they aren't going to give up.'"

One More Try

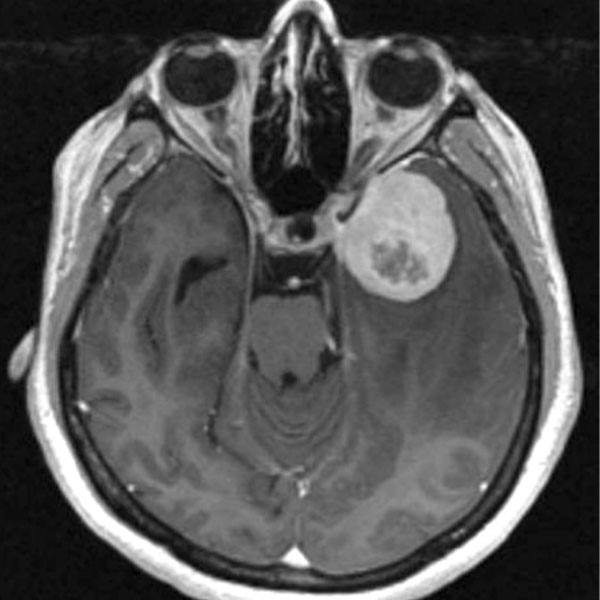

By March 2020, Anya was running out of options. In addition to the tumors in her lower spine, her positron emission tomography scan now showed suspicious activity in her upper spine. Doctors were concerned that she would be paralyzed soon.

They did another biopsy, which Karen Rech, M.D., a Mayo Clinic hematopathologist confirmed was consistent with the diagnosis of Erdheim-Chester disease. In addition, they sent off DNA from her tumor for another round of sequencing. As before, the sequencing failed to turn up any clearly pathogenic mutations. However, the report listed a "variant of unknown significance" — a genetic change whose impact on disease is unclear — in a gene called CSF1R.

"The variant had never been reported anywhere in the world," says Dr. Abeykoon.

Luckily, he was already familiar with CSF1R. The previous day, Dr. Abeykoon had treated one of his patients in the sarcoma clinic with pexidartinib, a CSF1R inhibitor that had been approved for a rare joint tumor known as tenosynovial giant cell tumor. There was a drug that could potentially treat Anya's cancer. But first, the researchers needed to determine whether the CSF1R variant of unknown significance found in her tumor was in fact significant.

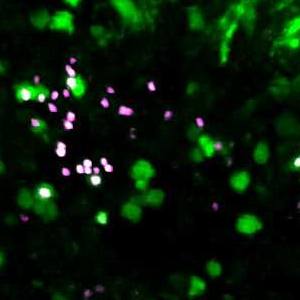

CSF1R is part of a family of genes that code for proteins known as colony-stimulating factors, named for their ability to stimulate the growth of entire colonies of cells in laboratory dishes. Mutations that activate genes like CSF1R have been shown to send cells growing out of control, fueling the development of tumors.

Dr. Abeykoon asked Terra Lasho, Ph.D., a Mayo Clinic molecular biologist, to investigate whether Anya's mutation was activating.

She mapped the sequence and found that the mutation disrupted a part of the CSF1R protein known as the "autoinhibitory region," which keeps the protein's activity in check. The disruption short-circuited the protein's ability to shut itself down, forcing it into a state of perpetual activity.

"I knew it was an activating mutation," said Dr. Lasho, "so I emailed him back right away and told him we have to pursue this."

But when Dr. Abeykoon applied for Anya's insurance company to cover pexidartinib, which inactivates CSF1R, he was promptly rejected. No one had ever used the drug to treat blood cancer before, and the insurers wanted to see evidence that it would work.

He tried to convince them again. And again. Finally, on the fourth try, he got someone from the insurance company on the phone and said, "If this was your daughter, and she was going to die in a month, what would you do?" They offered to insure the drug for a three-month trial.

A path forward

Anya started taking the medication right away. Within weeks, she had regained her vision and her ability to walk. Three months later, a positron emission tomography scan indicated that the dark masses running up and down her spine had completely melted away. An MRI also showed no signs of disease.

Dr. Abeykoon recalls being "excited, cautiously excited" when he told Anya and Colleen that the treatment was working. Colleen remembers having no reaction to the news, as she and her daughter sat stone-faced, side by side. Things had been so bad for so long.

"You have to realize that is how she and the entire family have survived is by basically not getting too upset when things are awful. But at the same time, you kind of steel yourself from getting too happy (when there's reason to hope)," says Colleen. "It took a really long time to even begin to accept and believe that there was a path forward for a future."

Unlike the relentless side effects that Anya experienced with previous medications, this one only had one apparent downside: It turned her hair white.

As her health returned, Anya said yes to everything, possessed with the desire to make up for lost time. She got a master's degree in communications, earning her undergraduate and graduate degrees (in sickness and during a pandemic). She dyed her hair red, made new friends, traveled and worked three jobs.

The next challenge

So it seemed, Anya could finally resume her highly active life and pursue her career goals. Yet despite her apparent cancer remission, her biggest challenge was about to occur.

Last October, Anya was walking across the street with a small group of friends after their shift at a Minneapolis restaurant when the driver of an SUV hit her, throwing her more than 30 feet. The crash shattered her pelvis, broke her leg in three places, cracked her eye socket and fractured two bones at the base of her skull. It also left her with a traumatic brain injury.

She spent 28 days in the hospital and was off the cancer drug the entire time, prompting concerns that her tumors might return. Just as no one had ever used this drug to treat her cancer before, no one had ever stopped it so abruptly.

Anya returned to Mayo Clinic for a follow-up appointment in March. Though her bones had all healed, she was still adjusting to the realities of life with a traumatic brain injury. The looming question was whether she would have to deal with her recovery while also battling a resurgence of her cancer. She hadn't noticed any of her old symptoms resurfacing. By every indication, she appears to have remained cancer-free.

Anya is making slow but steady progress on regaining her abilities from the brain injury. The same determination and spirit that carried her through her cancer odyssey is now helping her meet the difficulties of this latest challenge.

As for the cancer, Dr. Go feels remarkably lucky at the outcome. He and other cancer researchers often search for a disease-causing mutation in their hardest-to-treat patients but never find one. They might find a mutation only to discover there is no off-the-shelf drug available to target it. And because many cancers are caused not by a single "driver" mutation but several, they might knock one mutation down only to have another step up to fuel the cancer.

"So, you have to be lucky on many levels," says Dr. Go.

Given all the challenges this individualized medicine approach entails, the story of Anya's success has taken on even more meaning.

"You might say our team helped her, but she really helped us," says Dr. Lasho. "Her success motivates us to keep going and to push the science forward."

Recently, Mayo began treating another patient, a young woman who was even worse off than Anya. Two months after taking pexidartinib, she went from being bedridden to walking again. She and Colleen have begun texting back and forth, as she, too, benefits and learns from Anya's story, even as it continues to unfold.

"It's not just that Mayo saved her life," says Colleen. "They saved her life using a way that didn't exist before they came up with it."

- Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., May 3, 2022