-

Improving Access to Deep-Seated Brain Tumors

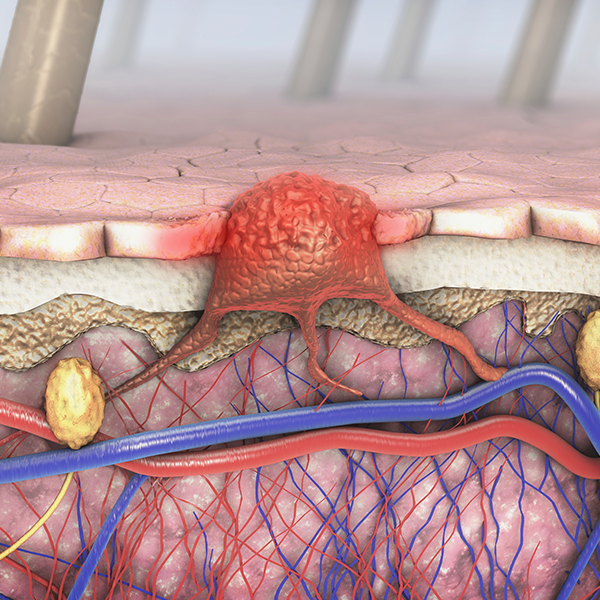

When it comes to treating tumors deep in the brain, such as those near the thalamus and basal ganglia, surgery has long presented a significant challenge. The traditional methods of accessing these tumors can pose risk to the surrounding healthy brain tissue. That’s why patients with deep-seated, aggressive tumors, like gliomas, sometimes have to forgo the surgical removal of the mass before chemotherapy and radiation.

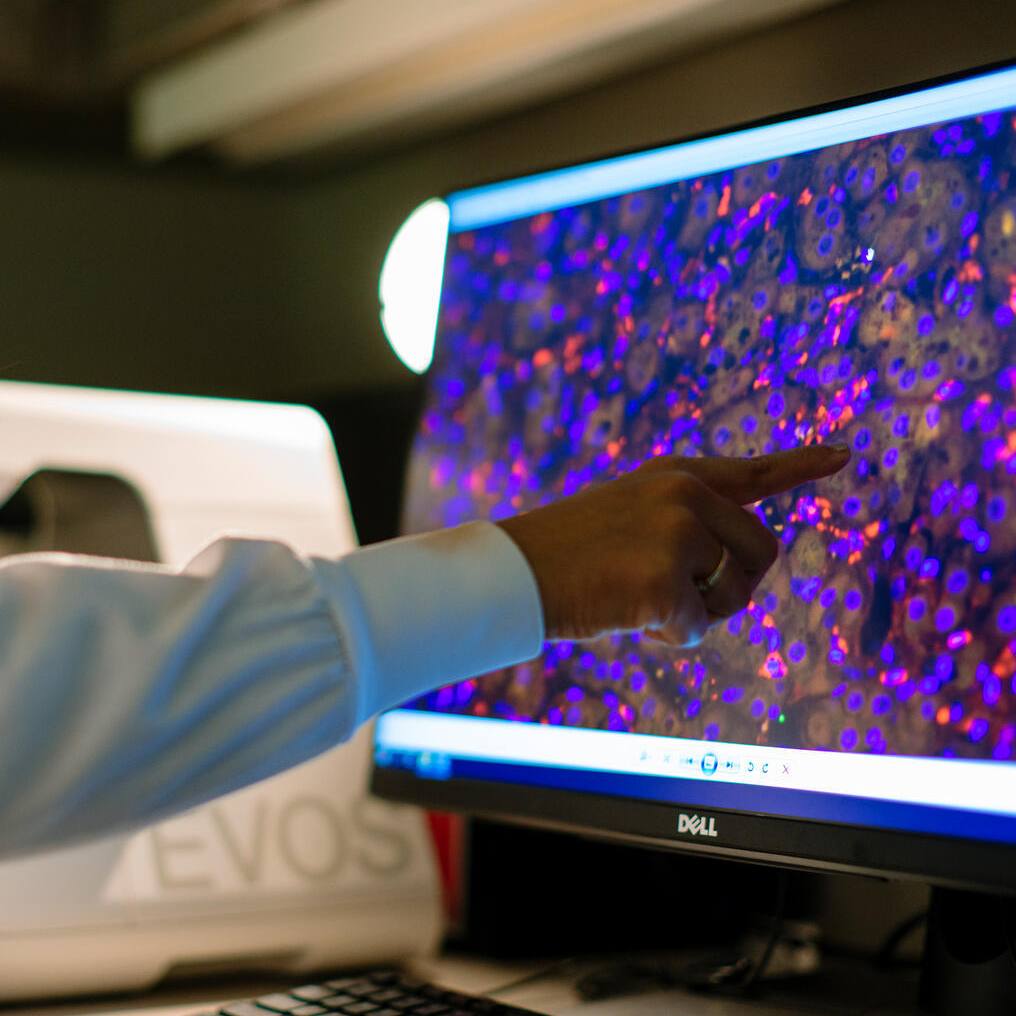

In a study published in Journal of Neurological Surgery Part A, neurosurgeon Kaisorn Chaichana, M.D., has found deep-seated gliomas can be removed in the operating room, using a new type of retractor that enables surgical tools to approach the tumor without damaging other brain structures. “With the traditional approach, surgeons might only biopsy deep-seated tumors because they don’t want to cause collateral damage associated with accessing and removing the tumor,” says Dr. Chaichana, on Mayo Clinic’s campus in Florida. “We’ve now found we can resect these tumors with minimal damage.”

The new approach doesn’t involve the standard metal, spatula-like retractors used to keep the folds and curves of healthy brain tissue out of the way. Instead, a “tubular retractor” made of flexible, plastic tubing the width of a dime can be eased through the white matter of the brain. Surgery begins with a small opening in the skull, resulting in minimal blood loss. With a camera hovering over the top of the tube, the surgical tools are threaded through the retractor to the site of the tumor. “The surgeon has to be comfortable working in a very narrow corridor. But the tube doesn’t damage the healthy brain tissue, it just displaces it,” Dr. Chaichana explains. “Then, when the surgery is over, the tissue just moves back into place.”

The tubular retractor had been used to remove intracranial hemorrhages, but had never been tested in the treatment of brain tumors until Dr. Chaichana began studying whether it might ease biopsies of deep-seated high-grade gliomas. When those procedures were successful, he began testing the same minimally invasive approach to remove tumors. Because the tube causes little damage, he adds, tumors that grow back can likely be approached surgically a second time through the same route. However, his goal is to minimize the chance of recurrence by removing as much tumor as possible during a first surgery.

Dr. Chaichana intends to continue advancing the use of the tubular retractor, determining whether it can be applied to the removal of additional masses, such as metastatic brain tumors. But the tool offers a new approach for an unmet patient need. “We now have the opportunity to remove deep-seated high-grade gliomas which may offer patients better outcomes,” he says.