-

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Acoustic neuroma — to treat or not to treat?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I was diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma last year. My doctor says I likely won't need treatment. But I know others who have had the same condition and had surgery to remove the tumor. Why would I not need any treatment?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I was diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma last year. My doctor says I likely won't need treatment. But I know others who have had the same condition and had surgery to remove the tumor. Why would I not need any treatment?

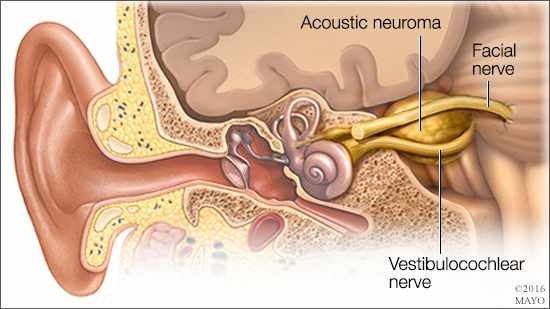

ANSWER: An acoustic neuroma, more accurately called a vestibular schwannoma, is a benign tumor that grows on the balance and hearing nerves. These nerves twine together to form the vestibulocochlear nerve, which runs from your inner ear to your brain. Hearing loss due to an acoustic neuroma often occurs predominantly on one side only. For many years, doctors thought surgical removal was the best treatment. Then, in the mid-1980s, stereotactic radiosurgery, such as Gamma knife radiosurgery, was shown to be safe and effective. Increasingly, doctors are concluding that, in some cases, no treatment may be just as good as or better than active intervention in the long run.

An acoustic neuroma arises from the cells (Schwann cells) that make up the insulation surrounding the vestibulocochlear nerve. What causes these cells to overgrow and form a tumor isn’t certain, but it may be related to sporadic genetic defects. Acoustic neuromas are uncommon and usually are diagnosed between ages 30 and 60. In rare cases, the overgrowth may be caused by an inherited disorder, called neurofibromatosis type 2.

Most acoustic neuromas grow very slowly, although the growth rate is different for each person and may vary from year to year. Some acoustic neuromas stop growing, and a few even spontaneously get smaller. The tumor doesn’t invade the brain but may push against it as it enlarges.

Signs and symptoms typically include loss of hearing in one ear, ringing in the ear (tinnitus) and unsteadiness while walking. Occasionally, facial numbness or tingling may occur. Rarely, large tumors may press on your brainstem, threatening vital functions. A tumor can prevent the normal flow of fluid between your brain and spinal cord so that fluid builds up in your head — a condition caused hydrocephalus.

Diagnosis can be a challenge because early signs and symptoms may be attributed to more familiar causes, such as aging or noise exposure. If an acoustic neuroma is suspected, such as when a hearing test reveals loss predominantly in one ear, the next step is to undergo imaging — typically an MRI — to look for evidence of a tumor on the vestibulocochlear nerve. Increasingly, acoustic neuromas are being discovered as incidental findings when people undergo an MRI scan for unrelated reasons, such as chronic headache, multiple sclerosis or even during surveillance imaging for another unrelated tumor.

Treatment varies depending on the size and growth of the acoustic neuroma, symptoms, and your personal preferences. Options include:

- Monitoring — If you have a small acoustic neuroma that isn’t growing or is growing slowly and causes few or no signs or symptoms, your doctor may decide to monitor it. It sounds like this is what your doctor has recommended for your situation. Recent studies indicate that more than half of small tumors don’t grow after diagnosis, and a small percentage even shrink. Monitoring involves regular imaging and hearing tests, usually every six to 12 months. The main risk of monitoring is tumor growth and progressive hearing loss.

- Stereotactic radiosurgery — This approach may be used if the acoustic neuroma is growing or causing signs and symptoms. In this procedure, doctors deliver a highly precise, single dose of radiation to the tumor. The procedure’s success rate at stopping tumor growth is usually greater than 90 percent. Although the risk is small, stereotactic radiosurgery can damage nearby balance, hearing and facial nerves, worsening symptoms or creating new ones.

- Open surgery — Surgical removal typically is recommended when the tumor is large or growing rapidly. This involves removing the tumor through the inner ear or through a window in your skull. If it can be removed without injuring the nerves, your hearing may be preserved. Surgery risks include nerve damage and worsening of symptoms. In general, the larger the tumor, the greater the chances of your hearing, balance and facial nerves being affected. Other complications may include a persistent headache.

Research is ongoing to compare the three treatment strategies. But, based on long-term data, there appears to be surprisingly little difference in outcome no matter which treatment is chosen for smaller tumors. Talk to your doctor to make sure you are being monitored appropriately for your situation. (adapted from Mayo Clinic Health Letter) — Dr. Michael Link, Neurologic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota