-

Cardiovascular

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Congenital heart defect can affect health of mother and baby

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: My husband and I are hoping to start a family soon, but I have a congenital heart defect — a bicuspid aortic valve. I’m concerned how that will affect my pregnancy. What do I need to consider before getting pregnant? What are the risks?

ANSWER: A congenital heart defect can affect your health — and potentially the health of your baby — during pregnancy. But the presence of a congenital heart defect doesn’t necessarily mean you should not get pregnant.

A good first step for you would be to find a cardiologist who is board-certified in adult congenital heart disease and has experience in evaluating and managing heart patients considering pregnancy. He or she can review your current health and medical history, and talk with you about potential pregnancy risks and how you may be able to manage them. In addition, he or she can discuss with you the likelihood that your child will have a congenital heart defect.

Congenital heart defects — abnormalities in the structure of the heart that are present at birth — are common, affecting about 1 in 100 live births. Due to advances in care, most individuals born with congenital heart defects who may not have survived 40 years ago are now living and thriving as healthy, productive adults with families of their own.

For women with congenital heart defects — even those successfully treated when they were children — pregnancy can present health challenges. Pregnancy places extra stress on the heart and circulatory system. During pregnancy, a woman’s blood volume increases by 30 to 50 percent, the heart pumps more blood each minute, and the heart rate increases. Labor and delivery add to the heart’s workload. After delivery, it takes several weeks for the stresses on the heart to ease and heart function to return to normal.

When one of the heart valves is abnormal, as in your situation, it may be harder for the body to tolerate the increased blood flow associated with pregnancy. In some cases, there may be a higher risk of infection in the lining of the heart or in the heart valves during pregnancy.

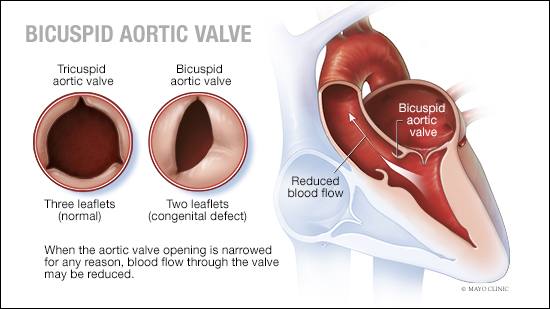

Women with a bicuspid aortic valve — in which the valve has only two leaflets rather than three — also may have dilatation of the ascending aorta, which can present unique concerns when pregnancy is being considered. That condition can be detected during an echocardiogram performed as part of your prepregnancy evaluation.

Research has shown that bicuspid aortic valves often run in families. That means you may need additional monitoring and ultrasound scans during pregnancy to check your baby’s heart valves as he or she develops.

To evaluate your risks and help you plan for pregnancy, consult with a physician who specializes in adults with congenital heart defects. Ideally, this would be someone with experience and expertise working with pregnant women who have heart disease — a subspecialty known as maternal cardiology. This physician should work closely with a maternal fetal medicine specialist, an obstetrician who is trained to evaluate and care for patients like you.

The health care organization you choose should have specialists in genetics and cardiac surgery — in addition to cardiology, obstetrics and pediatrics — who will work together to provide a full spectrum of care throughout pregnancy for you and your baby.

As you consider becoming pregnant, be aware, too, that some congenital heart defects can affect fertility. So that’s another topic to discuss with your cardiologist. If fertility is a concern, he or she can help you identify options and fertility specialists in your area, if needed.

Many women with congenital heart defects have successful pregnancies. But it’s important to understand your individual risks and to work with a health care team that’s well-equipped to deal with any complications that may arise during pregnancy. — Dr. Naser Ammash, Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota

****************************

Related Articles

- Women’s Wellness: Congenital heart disease and pregnancy published 2/21/19

- Sharing Mayo Clinic: A personalized approach to heart health published 7/15/18

- Mayo Clinic Radio: Congenital heart defects published 4/26/18

- Women’s Wellness: Know the risks of heart conditions and pregnancy published 3/1/18