DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I was diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus three months ago and was given some diet instructions, including eliminating alcohol and caffeine. Why is this necessary? Is it still possible for me to have an occasional alcoholic drink? Is decaffeinated coffee OK?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I was diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus three months ago and was given some diet instructions, including eliminating alcohol and caffeine. Why is this necessary? Is it still possible for me to have an occasional alcoholic drink? Is decaffeinated coffee OK?

ANSWER: One of the main goals for the management of Barrett’s esophagus is controlling esophageal reflux. The diet guidelines you were given often can help control reflux and reduce its symptoms. But if symptoms don’t bother you when you have those foods or beverages, then you may not need to avoid them completely.

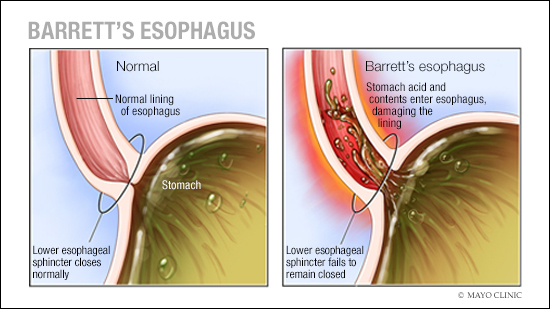

In Barrett’s esophagus, part of the normal tissue in the tube connecting your mouth and stomach — the esophagus — is replaced by tissue similar to the intestinal lining. Barrett’s esophagus is caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD. Everyone who develops Barrett’s esophagus has, or has had, GERD. But not everyone experiences symptoms. In some people, the symptoms of reflux are readily apparent. They include heartburn, regurgitation, throat clearing, hoarseness, nausea or indigestion. But some people with Barrett’s esophagus don’t have reflux symptoms. Or they may have them for some time, but the symptoms go away.

The reason for lack of symptoms in some people is due, in part, to the way Barrett’s esophagus develops. The medical definition of Barrett’s esophagus is intestinal metaplasia of the esophagus. That means the normal cells of the esophagus, called “squamous cells,” are replaced by intestinal cells. “Metaplasia” means the replacement of one cell by another cell. When metaplasia happens, the first type of cell usually is more vulnerable to injury than the type of cell that replaces it.

In Barrett’s esophagus, the body decides to, in effect, wallpaper the esophagus with intestinal cells. This decision is due to GERD. The intestines are located just beyond the stomach, and the stomach produces a significant amount of acid. Some of the excess acid from the stomach passes into the intestine, and the intestinal cells aren’t irritated by it. So when intestinal cells replace squamous cells in Barrett’s esophagus, acid reflux isn’t as damaging to the esophagus. Because intestinal cells are more resistant to acid, some people with Barrett’s esophagus do not feel the effects of the reflux.

In people with Barrett’s esophagus who are affected by reflux symptoms, the symptoms may be triggered by certain foods, especially spicy, citric or hot foods, as well as other stimuli, such as alcohol and coffee. These foods and beverages have a tendency to cause symptoms because they reduce pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter, and that allows more acid to come into the esophagus. They also may act as an irritant, and they can affect the way the stomach empties, both of which can lead to symptoms.

The severity and frequency of symptoms caused by diet varies quite a bit from one person to another. For example, whereas coffee may predictably cause reflux symptoms in some people, in others, it causes no symptoms at all. And in some cases, if certain diet choices cause symptoms before the patient is treated with an acid-suppressing medication, symptoms may go away with those medications. The most common medicines used to suppress acid are proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers.

When certain foods and beverages cause reflux symptoms, it would be wise to avoid them or use them sparingly. If they do not cause symptoms, or if acid-suppressing medications prevent symptoms, then it’s likely that you don’t need to completely eliminate those foods and beverages from your diet, and you may use them in moderation.

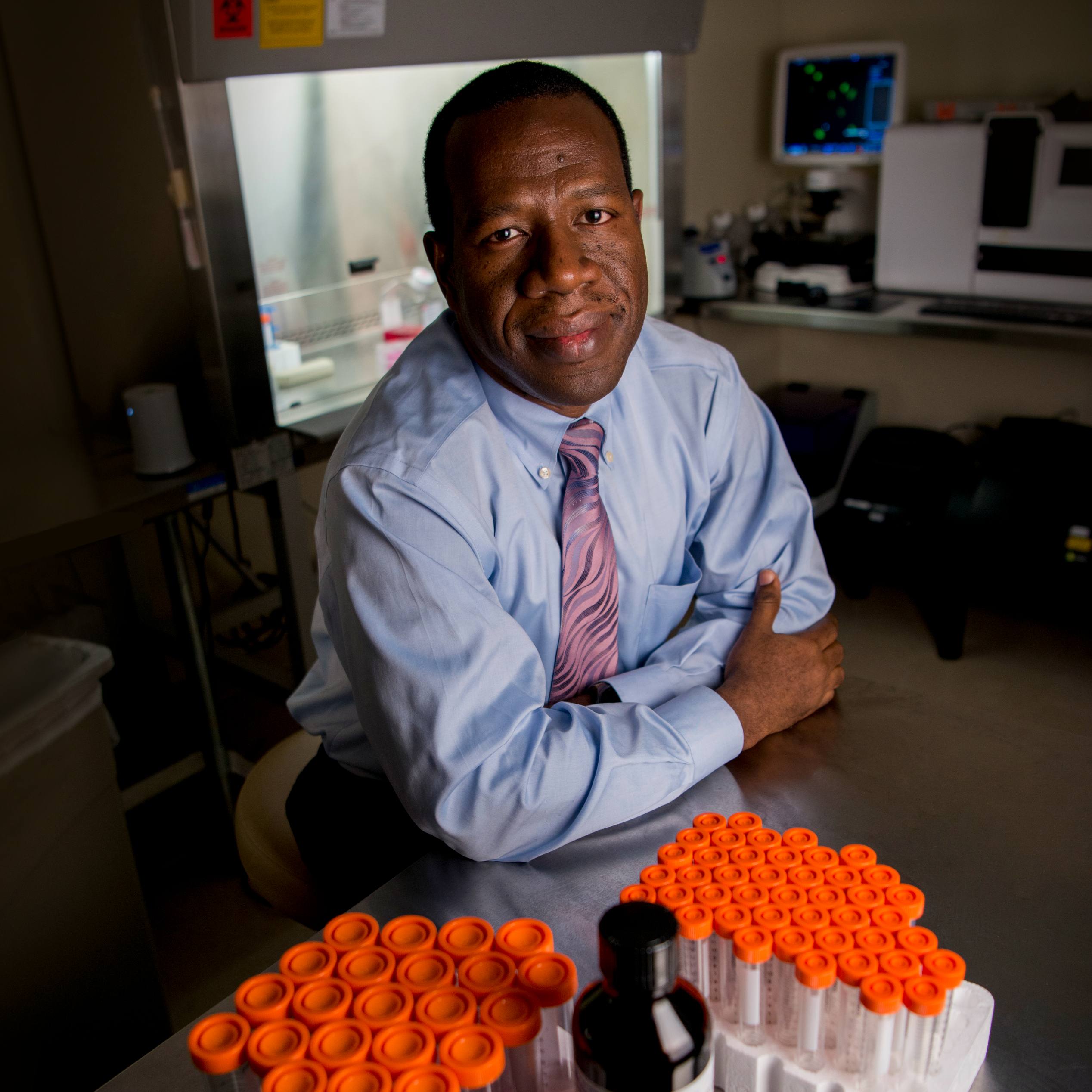

Before you decide which foods and beverages to avoid — or not — due to Barrett’s esophagus, check with your health care provider to make sure that your choices are a good fit for your health overall. — Dr. David Fleischer, Gastroenterology, Scottsdale, Arizona