-

Health & Wellness

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Medication may help slow progression of PBC

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I was diagnosed with primary biliary cirrhosis three months ago. I don’t have any symptoms yet but wonder what I should look for. Are there things I can do to slow its progression?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I was diagnosed with primary biliary cirrhosis three months ago. I don’t have any symptoms yet but wonder what I should look for. Are there things I can do to slow its progression?

ANSWER: Your situation is common. Most people diagnosed with primary biliary cirrhosis, or PBC, in its early stages do not have any symptoms. Many remain symptom-free for years. Medication is available that can slow the progression of the disease, making it less likely that you will develop symptoms soon.

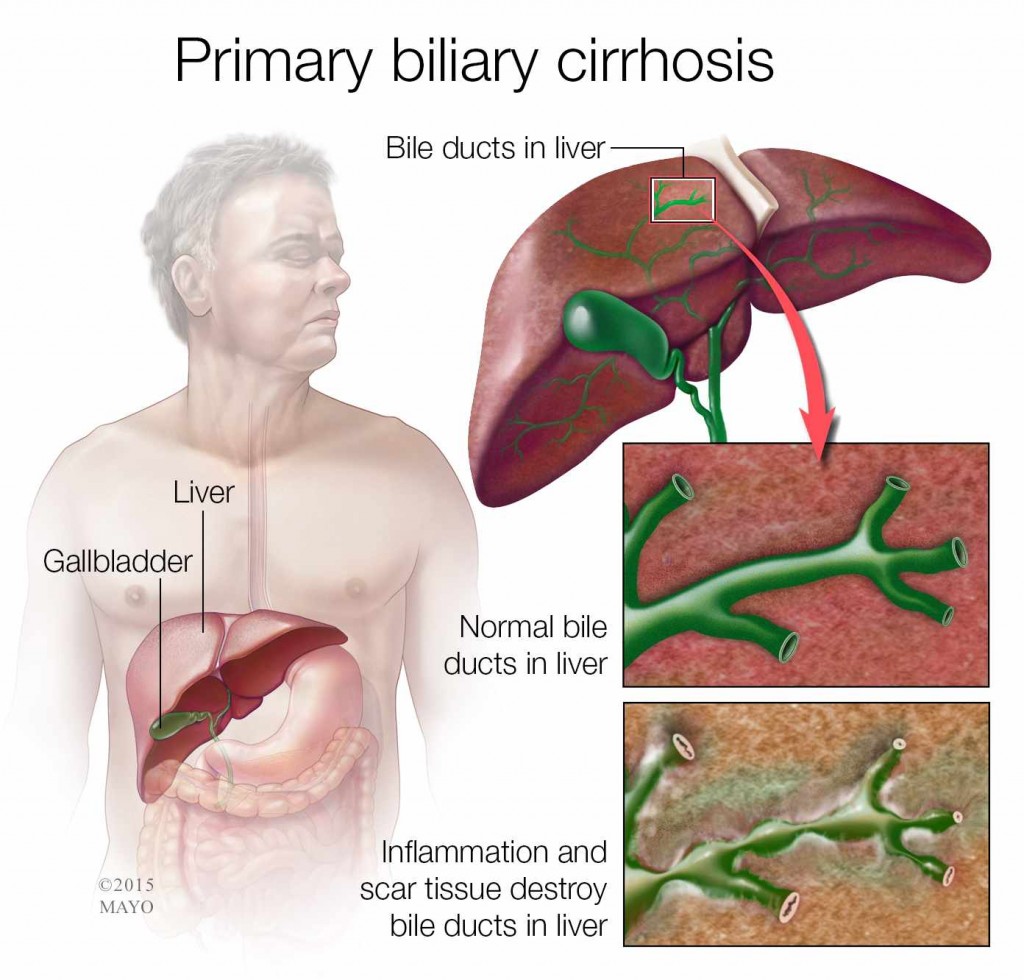

PBC is a disease in which the bile ducts in the liver become damaged. Bile, a fluid that your liver makes, plays a role in digesting food. It also helps your body get rid of worn-out red blood cells, cholesterol and toxins. When bile ducts don’t work the way they should, harmful substances can build up in your liver. In time, that may lead to irreversible scarring of your liver tissue.

PBC mainly affects women in their fifties. It isn’t clear what causes PBC, and in the disease’s early stages most people don’t know they have it. Many find out about PBC when results of a blood test done for another reason reveal that their liver enzyme levels are higher than normal. Additional blood tests usually confirm the diagnosis.

PBC is a slowly progressive disease. The disease often can be slowed further with a medication called ursodeoxycholic acid, or UDCA. Studies suggest that if UDCA is started in the early stages of the disease, it may extend life expectancy for people with PBC to the same point it would be if they did not have the disease. For the majority of people with PBC, this medication is all they need to substantially postpone PBC symptoms.

But even if you take UDCA, PBC symptoms may develop eventually. The most common symptoms are fatigue, weakness and itchy skin. Less common symptoms that usually appear after the disease has progressed significantly may include jaundice; bone, muscle and joint pain; fluid buildup; weak or brittle bones; and dry mouth and dry eyes, among others. A variety of therapies are available that can help keep these symptoms under control.

For a small number of people, UDCA is not effective in slowing the disease progression, and PBC eventually leads to liver failure. In those cases, a liver transplant typically is the only treatment option. Fortunately, transplants for PBC are much less common now than they used to be before UDCA became available. Research is underway to find additional treatment choices for those individuals who do not respond to UDCA.

Although uncommon, some people with the disorder have a family history of PBC. With that in mind, it is important for the women in your immediate family — your mother, sisters and daughters — to know about your PBC diagnosis, especially if they are middle-age. If results of blood tests show that they have elevated liver enzymes, they should be tested to check for PBC.

As you consider how to manage PBC over time, talk with your doctor about taking UDCA if you haven’t done so already. Also, set up a schedule for follow-up care. Regular checkups and blood tests allow your doctor to monitor your liver function and keep track of how quickly PBC is progressing. If you notice new or unusual symptoms at any time, contact your doctor right away. — Konstantinos Lazaridis, M.D., Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Related Articles