-

Mayo Clinic Q and A: No proven way to prevent celiac disease

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: Is there anything I can do now to prevent my 1-year-old from getting celiac disease?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: Is there anything I can do now to prevent my 1-year-old from getting celiac disease?

ANSWER: At this time, there is no proven way to prevent celiac disease. But if your child is considered to be at high risk for the disease due to family or medical history, there may be some steps you can take to lower that risk or to identify the disease early. If your child isn’t in a high-risk category, there’s no need to be concerned, as the possibility he or she will develop celiac disease is low.

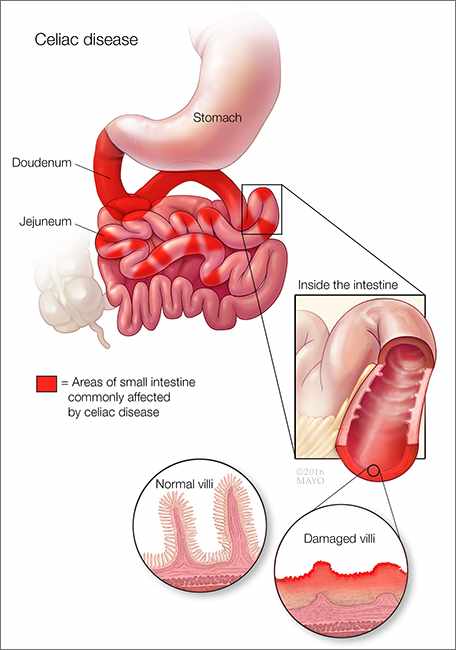

Celiac disease is an immune reaction to eating gluten — a protein found in wheat, barley and rye. For people with celiac disease, eating gluten triggers an immune response in the small intestine. Over time, that response damages the lining of the small intestine and prevents it from being able to absorb some nutrients. The intestinal damage can lead to diarrhea, fatigue, weight loss, bloating and anemia. In children, celiac disease also can affect their growth and development.

Anyone can get celiac disease, but it is much more common in people who have a family history of the disease or who have a medical condition that predisposes them to celiac disease. For example, the prevalence of celiac disease in the U.S. is about 1 percent for people who don’t have any risk factors for it. If a child has a parent or sibling with celiac disease, that number rises to around 5 to 10 percent. Some autoimmune disorders, such as Type 1 diabetes and certain thyroid conditions, also are associated with a higher risk of celiac disease. Genetic disorders, including trisomy 21 and Turner syndrome, can raise a child’s risk, too.

Anyone can get celiac disease, but it is much more common in people who have a family history of the disease or who have a medical condition that predisposes them to celiac disease. For example, the prevalence of celiac disease in the U.S. is about 1 percent for people who don’t have any risk factors for it. If a child has a parent or sibling with celiac disease, that number rises to around 5 to 10 percent. Some autoimmune disorders, such as Type 1 diabetes and certain thyroid conditions, also are associated with a higher risk of celiac disease. Genetic disorders, including trisomy 21 and Turner syndrome, can raise a child’s risk, too.

Two studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2015 showed that the timing of gluten introduction into the diet of children at higher risk didn’t lower the incidence of celiac disease. The studies found that delayed introduction of gluten actually may increase the risk. Some research suggests that the amount of gluten at the time it is introduced into a child’s diet may play a role, but there is no clear data on what is the right amount.

Based on those findings, the current recommendation is for parents of children at high risk for celiac disease to follow the guidelines issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics, or AAP, for food introduction.

If you have a family history of celiac disease, you could have your child tested to see if she or he has the permissive genotype for celiac disease, known as HLA DQ2/8. If the child doesn’t have it, you don’t need to worry about celiac disease.

If the child has that genotype, you should still introduce foods, including those that contain gluten, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. Then, you could consider having the child screened for celiac disease three to five years after gluten introduction — or sooner if you notice symptoms that could be related to celiac disease.

If you’re concerned about celiac disease, talk to your child’s health care provider. He or she can answer your questions and provide more information on the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for when to introduce new foods into your child’s diet. — Dr. Imad Absah, Pediatric Gastroenterology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota

Related Articles