-

Featured News

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Protecting yourself from Lyme disease

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: Each summer, some friends and I spend a week camping in a wilderness area in northern Minnesota. When we got back this year, a member of our group was diagnosed with Lyme disease. As we get ready to go next time, what should we do to protect ourselves from Lyme disease?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: Each summer, some friends and I spend a week camping in a wilderness area in northern Minnesota. When we got back this year, a member of our group was diagnosed with Lyme disease. As we get ready to go next time, what should we do to protect ourselves from Lyme disease?

ANSWER: Lyme disease is a common illness spread by ticks that tend to live in long grasses, bushes, shrubs and forested areas, particularly in the Midwest and Northeast U.S. Spending a week in a northern wilderness does raise your risk for contracting Lyme disease. Unfortunately, there is no longer a vaccine for prevention of Lyme disease. But there are steps you can take to prevent it.

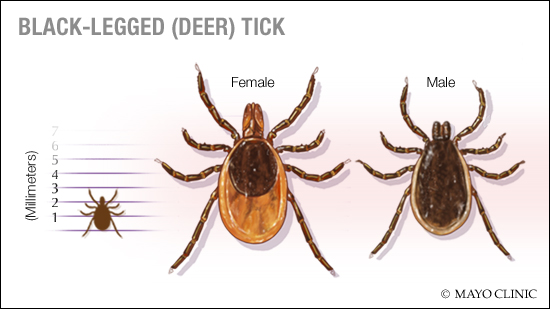

Lyme disease is caused by specific strains of bacteria. Black-legged ticks, also known as deer ticks, which feed on the blood of animals and humans, can carry the bacteria and spread it when they feed.

Deer ticks attach easily to bare skin. One of the most effective ways to deter ticks is to wear clothing that covers your arms and legs, including long-sleeve shirts and long pants tucked into socks, along with a hat. As you pack for your trip, choose light-colored clothing. It allows you to more easily see the dark-colored ticks and remove them before they can reach your skin.

Footwear makes a difference, too. Ticks can attach to bare skin on your feet and then work their way underneath your clothing, making them hard to notice. Wear closed-toe shoes with socks. Avoid sandals or other open-toe footwear that leaves skin exposed.

If you prefer to be in shorts or short-sleeve shirts during your trip, then it's important to consistently wear tick repellent. To keep ticks away, the repellent you use should have a 20 percent or higher concentration of DEET.

Another insect repellent called permethrin can be used on your clothing. It doesn't just repel ticks, it kills them. Permethrin should not be applied directly to the skin. You can spray permethrin on clothing in advance so it has time to dry before you wear it, or you can buy clothing that already has permethrin embedded in the fabric.

During your trip, regularly check for ticks. If you notice a tick that's attached to your skin, take it off as soon as possible. The best way to do that is to use tweezers. Pinch down by the head where it’s attached to the skin. Don't squeeze, crush or twist it. Pull the tick straight out using consistent pressure.

If the tick is significantly swollen, that means it has been feeding for some time. Generally, a tick must be attached for 36 hours or more before it can transmit the bacteria that cause Lyme disease. If you find a swollen tick on your skin during your camping trip, contact your health care provider as soon as you get home. He or she may recommend you take an oral antibiotic to prevent Lyme disease.

Symptoms of early-stage Lyme disease include a flu-like illness that usually involves aches and pain. Some people develop a fever, but others do not. The hallmark symptom, though, is a bull's-eye rash at the spot where the tick attached. The rash appears in up to 80 percent of people with Lyme disease. It's normal for a small bump to develop after a tick bite. If over several days, however, the redness expands to form a rash with a red outer ring surrounding a clear area, then you will need medical attention and antibiotic treatment. Make sure your health care provider knows you've recently spent time outdoors in an area prone to ticks.

Treatment for Lyme disease usually involves a short course of oral antibiotics. If treated in its early stages, Lyme disease can be effectively treated without any long-term problems. — Dr. Gregory Poland, General Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota

****************************

Related Articles

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Will there be a Lyme disease vaccine for humans? published 9/18/18

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Tips to best remove ticks published 7/4/18

- Mayo Clinic Minute: What are the ABCs of avoiding ticks? published 5/21/18

- Uptick in vector-borne illnesses in US and what it means to you published 5/3/18