-

Featured News

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Some activities increase the risk of ACL injury

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I’m a 25-year-old woman, and I recently tore my ACL playing basketball. My doctor says I don’t need surgery and recommends physical rehabilitation instead. Can rehab completely fix the problem, so I can stay active? I love playing basketball and skiing. I don’t want to give them up, but I don’t want to wreck my knee either.

ANSWER: Surgery isn’t always necessary to treat an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear. Physical rehabilitation can strengthen the muscles around the joint and, in some cases, allow a return to physical activity. But, that’s usually true only if your activity does not involve aggressive cut and pivot movements, or jumping and high impact. The activities you mention, however, raise your risk for knee instability if you choose not to have your ACL repaired surgically.

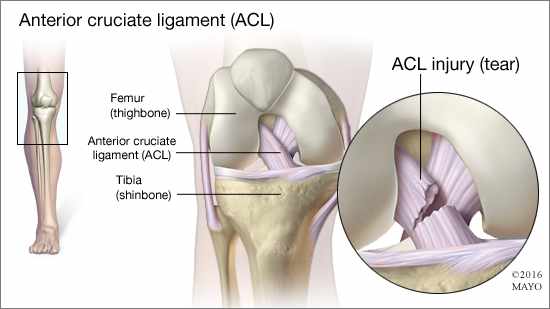

Ligaments are strong bands of tissue that connect one bone to another. Your ACL is one of two ligaments that cross in the middle of the knee and connect your thighbone, or femur, to your shinbone, or tibia. The ACL helps to keep your knee joint stable

When the ACL is torn, it usually causes knee pain and swelling. After an ACL injury, you also may feel instability in the knee or feel that the knee is "giving way" when you turn quickly or pivot. Often, a “pop” is heard or felt. ACL injuries frequently happen as a result of suddenly stopping, changing directions or pivoting. Sports that put you at risk of an ACL injury include basketball, singles tennis, football, volleyball and soccer. Downhill skiing also puts you at risk, because the length of a ski, combined with the rigidity of ski boots, places considerable force on your knee.

The purpose of treatment for an ACL injury is to reduce pain and swelling, restore normal knee movement, strengthen the muscles around the joint and allow a return to activity. For some people, this can be achieved with physical rehabilitation alone. If one of the menisci — the cushioning cartilage in the knee joint — is also torn, however, that can increase knee instability, making surgery the best option. It is worthwhile to note, too, that an ACL tear raises your risk of developing arthritis in your knee joint later in life. Studies show that risk to be similar whether or not you have surgical reconstruction.

Rehabilitation often involves working with a physical therapist to learn exercises that strengthen your leg muscles, as well as the muscles in your hips, pelvis and lower abdomen. Increasing muscle strength helps stabilize your knee joint, making it less susceptible to further injury.

To lower your risk of another ACL tear, a physical therapist should assess your movement patterns when you jump, land, pivot and change directions. Often, this will include a video analysis of how you land from a jump. Improving your movement patterns with corrective exercises can go a long way toward protecting against ACL injuries.

As you go back to your activities, having the proper gear also can help lower your risk of injury. Wear appropriate footwear when you play basketball. When you go downhill skiing, adjust your bindings correctly, so your skis will release when you fall. Some people wear a knee brace after an ACL injury, especially if they have not had surgical reconstruction. Research has shown, however, that wearing a brace does not appear to prevent or reduce the risk of an ACL injury.

If you continue to have episodes of knee instability despite physical rehabilitation or if you want to return to activities that place your knee at higher risk for further injury, consider ACL reconstruction surgery. Because a torn ACL can't be sewn back together, surgery involves replacing the torn ligament with a piece of tissue (i.e., a portion of your patellar or hamstring tendons) called a graft.

Talk to your doctor and your physical therapist about your sports and activity desires after your ACL injury. They can help you create a treatment plan that fits your goals and gives you the best odds for a safe return to activity. — Dr. Edward Laskowski, Sports Medicine Center, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota