DEAR MAYO CLINIC: My mother had a stroke six months ago. Her mobility has returned to near normal. She can read and understands others when they speak. But she has a lot of difficulty talking, often struggling to find the words she wants to say. She’s frustrated but refuses to go to speech therapy. She doesn’t think it will do any good. What does speech therapy after a stroke involve? Could it help someone like my mother?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: My mother had a stroke six months ago. Her mobility has returned to near normal. She can read and understands others when they speak. But she has a lot of difficulty talking, often struggling to find the words she wants to say. She’s frustrated but refuses to go to speech therapy. She doesn’t think it will do any good. What does speech therapy after a stroke involve? Could it help someone like my mother?

ANSWER: The overall effectiveness of speech therapy for people who have communication difficulties after a stroke largely depends on the area of the brain the stroke affected and the severity of the brain damage. Generally, speech therapy can help those whose speech is affected by a stroke.

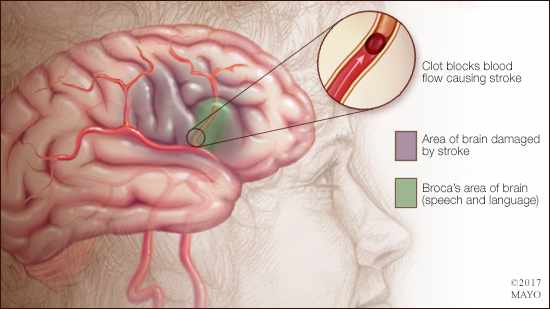

The most common type of stroke is an ischemic stroke, in which the blood supply to part of the brain is reduced significantly or cut off. As a result, brain tissue can’t get the oxygen and nutrients it needs. Within minutes, brain cells start to die. The brain damage caused by a stroke can lead to a variety of disabilities, including problems with speech and language.

The medical term to describe some of the communication problems that happen due to a stroke is "aphasia." There are several kinds of aphasia. The one you describe in your mother’s situation sounds like nonfluent, or Broca’s, aphasia. It occurs when a stroke damages the language network in the left frontal area of the brain. People with nonfluent aphasia typically can understand what others say, but they have trouble forming complete sentences and putting together the words they want to use.

Nonfluent aphasia, which can be a significant barrier to clear communication, often leads to frustration. Working with a speech-language pathologist can help. The goal of speech and language therapy for aphasia is to improve communication by restoring as much language as possible, teaching how to compensate for lost language skills, and learning other methods of communicating

Speech-language pathologists (sometimes called speech therapists) use a variety of techniques to improve communication. After initial evaluation by a speech-language pathologist, rehabilitation may include working one on one with a speech-language pathologist and participating in groups with others who have aphasia. The group setting can be particularly helpful, because it offers a low-stress environment where people can practice communication skills, such as starting a conversation, speaking in turn and clarifying misunderstandings.

A speech-language pathologist also can direct your mother to resources she can use outside of speech-language therapy sessions, such as computer programs and mobile apps that aid in relearning words and sounds. Props and communication aids, such as pictures, notecards with common phrases, and a small pad of paper and pen, often are encouraged as part of speech-language rehabilitation and can improve a person’s ability to convey his or her thoughts.

You, other family members, and friends also can help your mother rebuild her communication abilities. Consistently include her in conversations. Give her plenty of time to talk. Don’t finish her sentences for her or correct errors. Keep distractions to a minimum by turning off the TV and other electronic devices while you talk. Allow time for relaxed conversation.

Recovering language skills can be a slow process. With patience and persistence, however, most people can make significant progress, even if they don’t completely return to the level of function they had before a stroke. It is important to seek treatment for aphasia, because, if left untreated, communication barriers can lead to embarrassment, relationship problems and, in some cases, depression.

Encourage your mother to make an appointment with her health care provider to discuss speech-language therapy and help her find a speech-language pathologist who has experience working with people who have had a stroke. — Dr. Robert D. Brown, Jr., Neurology, and Dr. Heather Clark, Speech Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota