-

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Testing for the breast cancer gene

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: At my last mammogram, I asked my doctor if I could be tested for the breast cancer gene. She didn’t think it was necessary even though I have an aunt who had breast cancer. How do doctors decide who should be tested? Why shouldn’t all women be tested?

ANSWER: Genetic testing for the gene mutations associated with breast cancer, called BRCA1 and BRCA2, is offered to people who are likely to have inherited one of the mutations, based on their personal and family medical history. There are other newer genetic tests that may be available, too, depending on a person’s family cancer history.

BRCA gene mutations are uncommon. Affecting only about one percent of the population, they are responsible for approximately 5 to 10 percent of breast cancers. Because of their rarity, testing everyone for them isn’t necessary or recommended. If you’re concerned you might have one of these mutations, ask your doctor to help you assess your overall risk.

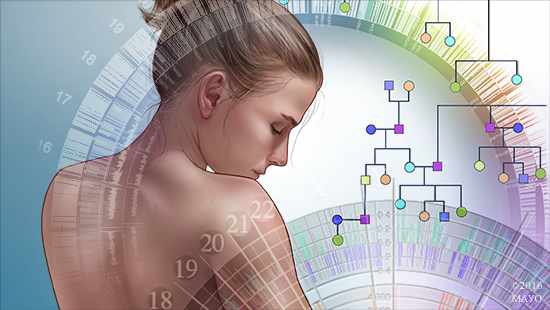

The first step in determining the possibility of a BRCA mutation is gathering a comprehensive family history. Your doctor would want to know if anyone in your family has had breast cancer or other types of cancer. If you have a first-degree relative with the disease — a parent, sibling or child — that has more of an impact on your risk than other relatives who have breast cancer, such as aunts or cousins. If you have a male relative with breast cancer, that could raise your risk more significantly, too.

The age a relative was diagnosed with cancer also makes a difference. People who have a BRCA gene mutation tend to develop breast cancer at a younger age than people who do not. If someone in your family had breast cancer before 50, that may increase the possibility a genetic mutation could be involved.

Typically, a family with BRCA will show a pattern of breast cancer that affects multiple family members over several generations diagnosed with breast cancer at young ages. But other cancer diagnoses should be reviewed, too. Ovarian, pancreatic or prostate cancer at a young age also could point to a hereditary predisposition to breast cancer.

If your family history suggests the possibility of a BRCA gene mutation, consider meeting with a genetic counselor before you make any decisions about testing. A genetic counselor can use your family history to calculate the family’s risk of hereditary breast cancer more specifically. He or she can help you fully understand the pros and cons of genetic testing. A genetic counselor also can offer guidance on the ideal individuals in the family to be tested first.

If genetic testing is recommended for you, you decide to have it done, and you learn that you do have a BRCA gene mutation, your risk for breast cancer would be much higher than normal. In women without BRCA, the odds of getting breast cancer are 1 in 8. For people with a BRCA mutation, lifetime risk for breast cancer ranges from 50 to 80 percent. With that in mind, women who carry the mutation should be referred to a breast health specialist or breast center to determine how often they should be screened for breast cancer and review possible medical and surgical treatment options that are available to them, based on their individual circumstances.

Keep in mind that, for most people, the likelihood of having a BRCA gene mutation is low ― even when a family member has had breast cancer. The vast majority of breast cancers are not inherited. It is important, however, for all women to be screened for breast cancer regularly. How often you need breast cancer screening tests should be based on your personal medical history, family history and preferences. Talk to your doctor about the schedule that best fits your needs. — Dr. Sandhya Pruthi, Breast Diagnostic Clinic, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota