-

Featured News

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Treating plantar fasciitis

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I am in my 60s and active. Over the years, I have had plantar fasciitis off and on, but the most recent episode has lasted longer than usual, and physical therapy hasn't helped much. What are my options for treatment at this point?

ANSWER: Most people with plantar fasciitis improve with basic care steps or physical therapy. However, healing can be slow and require perseverance. Newer, nonsurgical therapy options are helping with hard-to-treat cases.

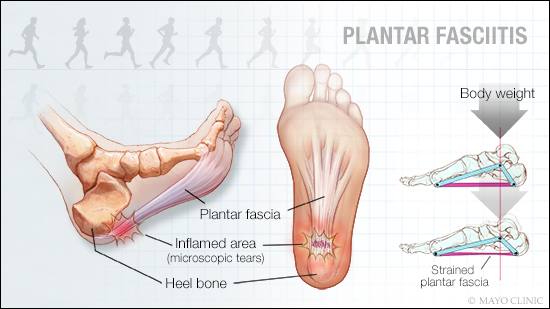

The plantar fascia is a fibrous band of tissue on the bottom of the foot. It connects the heel to the toes and supports the arch of your foot, acting as a shock absorber when you put pressure on your foot. Plantar fasciitis discomfort occurs at the bottom of your foot, typically near the heel bone. It can range from a dull sensation to piercing pain. Often, it comes on gradually and affects only one foot, though it can start suddenly and affect both feet.

Plantar fasciitis occurs when stress and strain cause microscopic tears in the fascia. There may be a temporary inflammatory reaction to the injury, but the true problem is degeneration of the fascia — not the inflammation.

The risk of plantar fasciitis is increased by factors that put extra strain on the feet, such as obesity; high-impact activities, such as running or dance aerobics; and certain faulty foot mechanics, such as flat feet, high arches or an abnormal walking pattern. Having a tight Achilles tendon or ankle muscles is also a risk factor. Risk rises if you suddenly increase your activity level, such as walking and standing a lot while on vacation. Going barefoot or wearing shoes with minimal support, particularly on hard surfaces, or routinely wearing high-heeled shoes also increases risk of injury.

To treat plantar fasciitis, the extra stress on the plantar fascia must be relieved, so that the tears can heel. For most people, these small tears can be treated successfully with physical therapy and special equipment that gives the foot extra support. A cortisone injection also may be considered.

But for some, this isn't enough, and finding a solution to the chronic pain and loss of function due to plantar fasciitis can be frustrating. Open surgery to remove the damaged tissue is an option, but recovery often is prolonged, and recurring pain is common.

If plantar fasciitis pain is disrupting your life and a thorough plan of care isn't leading to improvement after several months, newer, minimally invasive interventions can be effective.

Ultrasonic fasciotomy and debridement, a technology developed in part by Mayo Clinic doctors, uses ultrasound imaging to identify degenerated tissues and guide the entire procedure. Through a tiny incision, a needlelike surgical probe is inserted into the degenerated tissues. When activated, the probe tip vibrates rapidly, using ultrasonic energy to break up the damaged tissues, which then are suctioned away. The procedure usually takes only a few minutes, and the incision is closed with surgical tape.

Complications are uncommon. After about 10 days of rest or restricted weight-bearing, it's usually possible to return to your regular activities. However, physical therapy still may be needed, and it usually takes longer to get back to more strenuous activities.

Another treatment is called needle fasciotomy with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injection. Using ultrasound imaging and a thin probe, holes are poked in damaged and degenerated plantar fascia tissue. This is often followed by an injection of platelet-rich plasma into the fascia. Platelet-rich plasma is obtained from your own blood. Anti-inflammatory factors in platelet-rich plasma may help stimulate pain relief and healing in the area.

Talk with your health care provider to see if either of these treatments would be a good option for your situation. (adapted from Mayo Clinic Health Letter) — Dr. Arthur De Luigi, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona