-

Featured News

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Umbilical hernias in infants

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: My 2-month-old granddaughter’s belly button is very large and sticks out well beyond her tummy. What might cause this? Should we be concerned? Will it get smaller over time? It doesn’t seem to bother her, but I wonder if she should be seen by her doctor to have it checked anyway.

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: My 2-month-old granddaughter’s belly button is very large and sticks out well beyond her tummy. What might cause this? Should we be concerned? Will it get smaller over time? It doesn’t seem to bother her, but I wonder if she should be seen by her doctor to have it checked anyway.

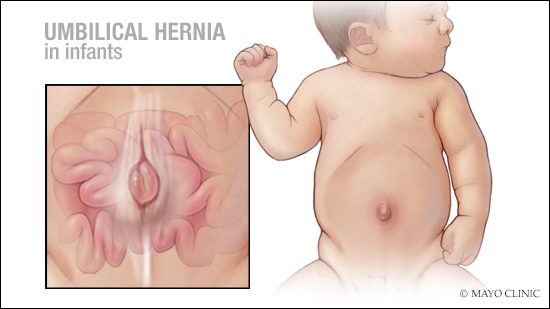

ANSWER: The condition you describe sounds like an umbilical hernia. It’s a fairly common condition among infants. In most cases, these hernias don’t cause any problems, and they often go away on their own over time. In some circumstances, surgery may be necessary to correct an umbilical hernia. Rarely, umbilical hernias can cause complications that require emergency medical care.

Before a baby is born, the umbilical cord passes into the abdomen through a small opening in the abdominal muscles. After birth, the opening in those muscles usually closes. An umbilical hernia develops when the abdominal muscles don’t close tightly over that opening, and part of the small intestine slides out through it, creating a soft bulge of tissue around the navel.

The size of these hernias can vary considerably, from the size of a pea to that of a small plum. Some may only be noticeable when the baby coughs, cries or strains.

Parents who suspect that their child has an umbilical hernia should have the infant evaluated by a health care provider. Umbilical hernias usually can easily be identified with a physical exam. In some cases, a health care provider may recommend an imaging exam, such as a CT scan or an abdominal ultrasound, to check for potential complications or underlying problems.

Most umbilical hernias are harmless and don’t require treatment. In children who develop an umbilical hernia before the age of 6 months, the hernia often goes away by the time the child is 3 or 4.

Although complications involving umbilical hernias are rare, they can happen. If the tissue that’s sticking out through the abdominal muscle opening becomes trapped (sometime referred to as “incarcerated”), blood flow to that tissue may be reduced. That can cause pain and tissue damage. If the blood supply to the trapped tissue becomes cut off completely, that may lead to tissue death — a condition called gangrene — and could trigger a serious infection that requires emergency care.

If a child who has an umbilical hernia has the following symptoms, seek emergency care right away: pain in the area of the hernia; tenderness, swelling or discoloration of the hernia; an inability to easily push in the hernia tissue; and vomiting or constipation. These symptoms may signal that a portion of the intestine has become trapped in the hernia.

If tissue becomes trapped within an umbilical hernia, surgery often is necessary. During the procedure, a surgeon makes a small incision near the hernia. The herniated tissue is repositioned in its proper place within the abdomen, and the abdominal muscles are stitched closed to prevent the hernia from coming back. This surgery also may be necessary if an umbilical hernia becomes painful, if it does not show any noticeable decrease in size by the time a child is 2, or if it doesn’t disappear by the time a child is 5.

There are some myths about ways to treat umbilical hernias, such as taping a coin over the hernia to hold it in. This isn’t necessary as the hernia doesn’t need to be covered by anything other than clothing. It also doesn’t need to be pushed on or forcefully pushed in. The only natural treatment is time, and if an umbilical hernia doesn’t eventually resolve on its own, a pediatric surgeon can help.

In most cases, though, surgery is not needed. Umbilical hernias typically are painless, and they get smaller as a child grows. Most are gone completely by the time a child reaches her or his fifth birthday. — Dr. Jason Homme, Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota