-

Cardiovascular

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Understanding and managing familial hypercholesterolemia

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: What is familial hypercholesterolemia? Is that just another way of talking about high cholesterol? How is it diagnosed?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: What is familial hypercholesterolemia? Is that just another way of talking about high cholesterol? How is it diagnosed?

ANSWER: Familial hypercholesterolemia is not the same as a typical case of high cholesterol. Familial hypercholesterolemia is an inherited condition that affects the way the body processes cholesterol. It results in high cholesterol in the blood and significantly raises the risk of a heart attack or stroke. Familial hypercholesterolemia can be detected with a genetic test. Once it’s identified, it often can be effectively treated.

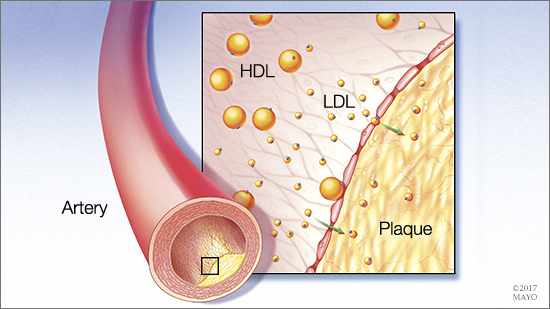

Cholesterol is a waxy substance that’s found in the fats in blood. While the body needs some cholesterol to build healthy cells, having too much cholesterol can cause health problems. In people who have familial hypercholesterolemia, a defective gene prevents the body from removing from the blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol — known as LDL (sometimes referred to as the “bad” cholesterol). Because of the extra cholesterol, plaque builds up in the arteries, causing them to narrow and increasing the likelihood of a heart attack or a stroke.

The gene mutation that causes familial hypercholesterolemia is passed from parent to child. Children with familial hypercholesterolemia inherit a defective copy of the gene from one parent. In most cases, they have one affected gene and one normal gene. In rare cases, a person inherits an affected copy of the gene from both parents. That leads to a much more severe form of the disease.

Familial hypercholesterolemia is a relatively common genetic condition. About 5 percent of the general population has high cholesterol as defined by LDL cholesterol greater than 190 milligrams per deciliter of blood. Of that group, about 5 to 7 percent have familial hypercholesterolemia.

Familial hypercholesterolemia can be serious and life-threatening. It typically does not cause any symptoms. If left untreated, it can lead to sudden cardiac death due to a heart attack, often before the age of 50. Because of the potentially devastating nature of this disease, it’s crucial that it is identified and treated early. Unfortunately, many people with familial hypercholesterolemia don’t know they have it. Current estimates are that only about 10 percent of those affected by the disease have been diagnosed.

Identifying who should be tested for familial hypercholesterolemia can be difficult, and there is some disagreement among researchers and physicians regarding screening guidelines. What everyone agrees on, though, is that when a person is diagnosed with familial hypercholesterolemia, all of the members of that individual’s family should be tested for the familial hypercholesterolemia gene mutation, too, particularly first-degree relatives — children, parents and siblings.

Diagnosing familial hypercholesterolemia involves a cholesterol check, called a lipid panel or a lipid profile, as well as a genetic test. As is common at most health care facilities, Mayo Clinic strongly recommends that patients meet with a genetic counselor before undergoing any genetic testing. The counselor can explain what the test involves and what it means, as well as the possible implications of the test results.

Once familial hypercholesterolemia has been diagnosed, treatment typically includes taking medication to lower LDL cholesterol. Adopting positive lifestyle choices, such as eating a low-fat diet, exercising and maintaining a healthy body weight, is always a good way to help ensure heart health and is recommended for people who have familial hypercholesterolemia. In most cases, though, lifestyle changes alone aren’t enough to lower LDL cholesterol to healthy levels in people who have familial hypercholesterolemia.

If you are concerned about the possibility of familial hypercholesterolemia in your family, especially if you have a family member who experienced a heart attack or stroke before age 50, talk to your health care provider about your risk factors for the condition and whether you should be tested for it. — Dr. Iftikhar Kullo, Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota