-

Cardiovascular

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Understanding and treating fibroelastomas

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I am an 83-year-old woman on warfarin because of atrial fibrillation, and I recently was diagnosed with a fibroelastoma. Could you give me a little information on what this is, including the treatment and prognosis?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I am an 83-year-old woman on warfarin because of atrial fibrillation, and I recently was diagnosed with a fibroelastoma. Could you give me a little information on what this is, including the treatment and prognosis?

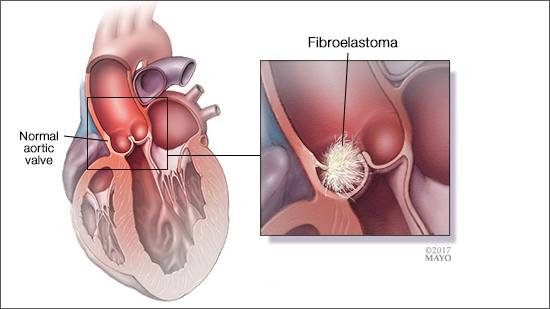

ANSWER: Fibroelastomas are formally known as papillary fibroelastomas, or PFEs, and are sometimes called cardiac papillomas. These small, noncancerous tumors develop in the heart — most often on one of the valves located between the heart chambers. Although they don’t involve cancer, these tumors still pose a health threat, because they can increase your risk of developing blood clots that could lead to a heart attack or stroke. Treatment typically involves surgery to remove the tumor. If that’s not possible due to other health considerations, then taking medication to lower the risk of blood clots is an option.

Tumors in the heart are rare, and they can be hard to diagnose accurately. Before you move forward with treatment, if your health care provider hasn’t already done so, it would be wise to confirm the diagnosis by ruling out other possible conditions that can mimic fibroelastomas.

For example, the diseases antiphospholipid syndrome and lupus can lead to heart valve masses that may appear to be fibroelastomas. Blood tests can rule out these conditions.

Also, what looks like a fibroelastoma on a standard echocardiogram, or EKG — an imaging test that shows the anatomy, structure and function of the heart — could actually be excess heart valve tissue or tissue that formed due to an infection that has healed. Another imaging exam called a transesophageal echocardiogram, or TEE, can allow your health care provider to get a more detailed look at the heart valves to help rule out these possibilities.

If it’s still hard to tell if the abnormality is a papillary fibroelastoma, your health care provider may recommend you continue taking the blood-thinning medication warfarin for six months to keep your risk for blood clots lowered. After that, the imaging exams can be repeated to see if the area in question has grown. If it’s the same size after six to 12 months, it’s less likely to be a fibroelastoma. If it has grown, then it is more likely to be a tumor.

To reduce the risk of blood clots and eliminate the possibility that the tumor could break off and cause other complications, it’s usually recommended that fibroelastomas be surgically removed. They often can be taken out without damaging the heart valve, but the procedure typically involves open-heart surgery. In some cases — particularly those in which the tumor is on the valve that’s between the chambers on the left side of the heart (the mitral valve) — a minimally invasive procedure that doesn’t involve opening the chest may be an option.

Once a papillary fibroelastoma is taken out, no further treatment usually is necessary. It’s rare for a fibroelastoma to redevelop after it’s been surgically removed, although it happens in approximately 2 percent of patients.

If your health care provider doesn’t recommend surgery for you due to your age, your overall health condition or other factors, then taking warfarin, aspirin or another medication to reduce your risk of blood clots may be necessary long term. In that situation, you also would need to have regular follow-up appointments that would include heart imaging exams to check your heart function and monitor your condition. — Dr. Kyle Klarich, Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota