-

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Understanding nearsightedness in children

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: My son is nearsighted and has been wearing glasses for three years. He’s now 10 and his prescription has gotten steadily worse. His optometrist says that it’s not uncommon for kids to need a new prescription every six to eight months, but I’m concerned. Should I take my son to an ophthalmologist for a full evaluation?

ANSWER: Your son’s changing eyesight sounds like it is within the normal range for a child his age. Unless he has other symptoms or other health problems that could affect his eyesight, it is unlikely that he needs a consultation with an ophthalmologist at this time.

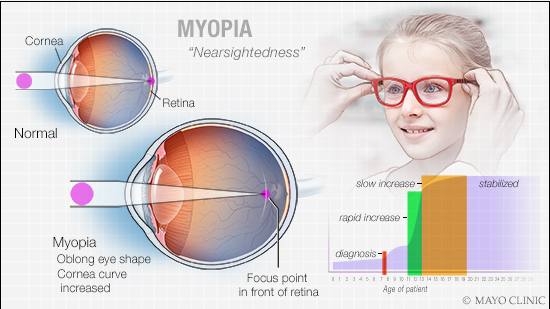

Nearsightedness, or myopia, is a condition in which you can see objects that are near to you clearly, but objects farther away are blurry. Nearsightedness happens when the cornea — the clear front surface of your eye — is curved too much or when your eye is longer than normal. That causes light coming into your eye to be focused in front of the retina at the back of your eye instead of directly on the retina. The result is blurry vision.

Many children develop nearsightedness during the early elementary school years, often around ages 7 or 8. The condition usually worsens throughout the teen years as a child grows. An increase in nearsightedness often is most rapid during early adolescence, around ages 11 to 13. It tends to slow and then stabilize by the late teens or early 20s.

It is uncommon for changing eyesight to be a symptom of another underlying medical condition. Some rare genetic disorders may be associated with nearsightedness. But in almost all cases, those conditions have other signs and symptoms that would accompany the vision changes.

Nearsightedness typically does not lead to other eye conditions or raise a child’s risk for additional eye problems, except in rare situations, such as the development of extreme nearsightedness.

Fortunately, nearsightedness can be corrected with eyeglasses or contact lenses. To keep a child’s prescription up to date, it is important to have regular eye exams. This is especially true during the years when eyesight is changing quickly. Timely exams can detect vision changes promptly so the prescription can be adjusted when needed.

Nearsightedness also can be treated with laser surgery of the cornea, but that approach generally is not recommended for children. Recent research has suggested that using eyedrops with the medication atropine may slow the progression of nearsightedness. Health care providers in the U.S. now use atropine for moderate levels of nearsightedness.

Although your son’s situation does not sound like it is out of the ordinary, have a detailed conversation with his eye care provider. Talk to your son’s optometrist about your concerns. Get more information about exactly how quickly your son’s prescription is changing and where that falls within the normal range. If you have any questions, ask.

If you still are worried or have additional concerns after that conversation, then it may be time to seek a second opinion or consider another provider for your son. An eye care professional trained and experienced in evaluating children — either an optometrist or an ophthalmologist — should be able to provide a thorough eye exam and offer clear information about a child’s eye health. — Dr. Brian Mohney, Ophthalmology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota