-

Featured News

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Why are kidney stones so painful?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: How do doctors decide on the best treatment for kidney stones? When I had a calcium stone, my doctor gave me medication and told me to drink plenty of water until it passed. When my mother had one, she went through a procedure to break up the stone. Why the difference? Also, what makes these stones so painful?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: How do doctors decide on the best treatment for kidney stones? When I had a calcium stone, my doctor gave me medication and told me to drink plenty of water until it passed. When my mother had one, she went through a procedure to break up the stone. Why the difference? Also, what makes these stones so painful?

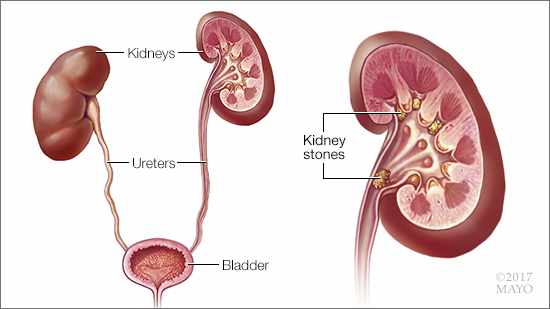

ANSWER: Treatment for kidney stones depends on a stone’s size, type and location. As in your case, extra fluids and medication may be all that’s needed for some small stones. Other treatment may be necessary when a stone is larger. The pain associated with kidney stones usually is the result of spasms triggered by a stone stuck in the ureter, coupled with pressure in the kidney from urine backup.

Kidney stones form from minerals and acid salts. About 85 percent of kidney stones are calcium-based, typically calcium oxalate. Less common are uric acid stones, struvite stones and cystine stones. Doctors use blood and urine tests to find out what kind of stones are present. If you have passed a stone, a laboratory analysis also can reveal the makeup of the stone.

Many uric acid and cystine stones can be dissolved by taking medication and drinking extra fluids. Calcium-based stones are different, because they don’t dissolve. You have to get them to pass through your urinary system or have them removed.

Drinking extra water can help flush out the urinary system, making it easier for a small stone to pass. Medication to relax the muscles in your ureter — the tube that connects your kidney to your bladder — also can help a stone pass more quickly and with less pain.

Kidney stones often can be quite painful. There are several reasons for that. First, the ureter is small and inflexible, so it can’t stretch to accommodate a stone. Second, when a stone gets into the ureter, the ureter reacts by clamping down on the stone in an attempt to squeeze it out. Those spasms can lead to significant pain. Third, if the stone is blocking the ureter, urine backs up into the kidney, causing pressure within the kidney.

People often describe kidney stone pain as flank pain that starts under the rib cage and goes down toward the testicles in men or the labia in women. To ease pain, health care providers often recommend over-the-counter pain relievers for those who are waiting for a kidney stone to pass. Sometimes, narcotics also are prescribed.

Stones that are too large to pass through the urinary tract on their own or stones that are causing other problems, such as bleeding, kidney damage or urinary tract infections, usually require more invasive treatment.

One procedure that can break up a kidney stone is called extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, or ESWL. It uses sound waves to create strong vibrations that break the stones into tiny pieces. Those pieces then pass out of the body in urine.

Another option to remove a stone in the ureter or kidney is a procedure in which a thin, lighted tube, called a ureteroscope, equipped with a camera is passed through the urethra and bladder to the ureter. Once the stone is located, special tools can snare the stone or break it into pieces that pass in the urine.

If a stone is particularly large, minimally invasive surgery may be necessary. A procedure called percutaneous nephrolithotomy involves surgically removing a kidney stone using small telescopes and instruments inserted through a small half-inch incision in the back.

Because you have a history of kidney stones, if you haven’t already done so, talk with your health care provider about strategies you can use to help prevent stones in the future. In many cases, dietary changes, an increase in fluids and, sometimes, medication can help reduce the risk of kidney stones. — Dr. David E. Patterson, Urology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota