-

Research

Meet Lisa Schimmenti: Searching for drug therapies to treat hearing loss

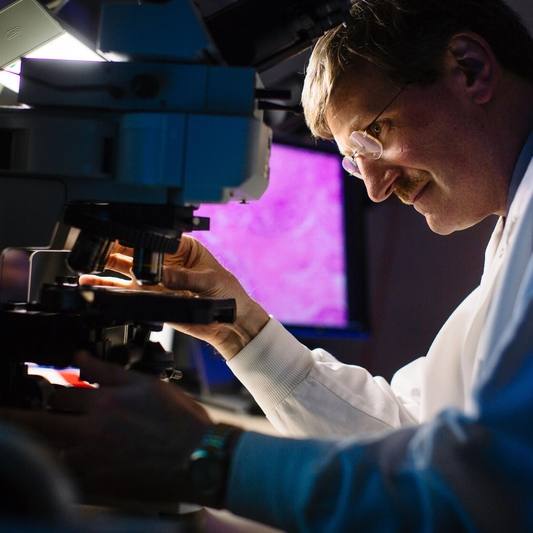

Lisa Schimmenti, M.D. has always been fascinated with Helen Keller and all she accomplished, in spite of being blind and deaf from a very young age. As the newly appointed chair of Mayo Clinic’s Department of Clinical Genomics and a medical geneticist, Dr. Schimmenti cares for patients with similar conditions.

In her clinical practice, she sees children and adults with Usher syndrome, a rare genetic condition that causes deafness or profound hearing loss at birth and blindness by the time a child turns five. With support from the Center for Individualized Medicine and the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Dr. Schimmenti is using zebrafish to search for drug therapies that could help restore hearing for these patients.

During her career, she’s seen how genomic discoveries have uncovered the causes of many rare diseases and led to the development of new targeted treatments for many more common diseases like cancer and heart disease. Now in her new role overseeing the Department of Clinical Genomics, Dr. Schimmenti is working to extend genomics medicine across all specialties at Mayo Clinic.

“Our clinical geneticists and genetic counselors are collaborating with all departments to facilitate the use of the latest genomic testing technologies to help improve care for all patients.” – Lisa Schimmenti, M.D.

“Our clinical geneticists and genetic counselors are collaborating with all departments to facilitate the use of the latest genomic testing technologies to help improve care for all patients,” says Dr. Schimmenti.

Here’s a closer look at how she’s using the latest genomics tools in her own research to uncover a treatment for hearing loss.

Restoring hearing to boost language development

For newborns diagnosed with Usher syndrome, the only current treatments available for hearing loss are devices such as hearing aids or cochlear implants. However, cochlear implants cannot be implanted until an infant is 12 months old and many infants do not benefit from a hearing aid alone.

“If we can identify a drug to improve hearing, we can help newborns hear sooner, at a time when language development is so critical. They may then be able to use a hearing aid while awaiting a cochlear implant,” says Dr. Schimmenti.

Zebrafish – the perfect model for drug discovery

Dr. Schimmenti and her team are using zebrafish, a type of freshwater fish, to test drug compounds to improve hearing.

“We are able to use zebrafish to model the conditions that we see in the clinic because they share 70 percent of their genes with humans. The same gene that causes Usher syndrome in humans also causes the syndrome in zebrafish,” says Dr. Schimmenti.

The research team tests different therapies by putting the medication into the water. They then measure changes in the hair cells on the zebrafish, which are an important link in the sensory process for hearing, to identify any changes.

The team’s early research results are promising. The next step is to test therapies that have been shown to improve hearing in mouse models.

“While we are early in the research process, the prospect of finding a drug to bypass some of the genetic defects in the sensory process that are causing deafness is very exciting. It’s possible that these therapies could also be applied to treat hearing loss caused by other conditions. For example, some cancer treatments can cause nerve damage and hearing loss. The implications of these discoveries could eventually be far reaching." – Dr. Schimmenti

“While we are early in the research process, the prospect of finding a drug to bypass some of the genetic defects in the sensory process that are causing deafness is very exciting. It’s possible that these therapies could also be applied to treat hearing loss caused by other conditions. For example, some cancer treatments can cause nerve damage and hearing loss. The implications of these discoveries could eventually be far reaching,” says Dr. Schimmenti.

A passion for genetics

Dr. Schimmenti became interested in genetics early in her medical training. However, she chose a different path before returning to genetics as the focus of her career.

“During my pediatrics training at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, I saw many young patients with severe hearing loss and was surrounded by outstanding mentors who were working to uncover the genetic causes of these conditions. But at the time, the Human Genome Project, the first mapping of an entire human genome, had not been completed. Genomic discovery was in the early stages, so I chose to pursue a fellowship in critical care at Yale University rather than continue in genetics,” says Dr. Schimmenti.

As progress in genomic discovery continued and genetic variants linked to hearing loss were identified. Dr. Schimmenti decided to return to her true passion – working in the lab to uncover new therapies for the patients with rare genetic diseases that she cared for in the clinic.

She returned to University of Minnesota to complete her genetics fellowship and begin her work using zebrafish to better understand the genetic and molecular processes driving hearing loss.

And she’s never looked back.

“It’s exciting to use genomics to search for a drug that could treat hearing loss and make a real difference for patients. At the same time, I am excited to collaborate with all medical specialties across Mayo Clinic to see how we can extend genomics services to all patients and enhance individualized care for many conditions,” says Dr. Schimmenti.

Learn more about individualized medicine

For more information on the Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine, visit our blog, Facebook, LinkedIn or Twitter at @MayoClinicCIM.

See highlights from Individualizing Medicine: Advancing Care Through Genomics, which was held Sept. 12-13 in Rochester, Minnesota:

- CIM CON day 1 – Precision cancer care: ‘So much power’

- CIM Con day two: Unlocking the mystery of rare diseases

- CIMCON18 — how genomics discovery is transforming individualized care and the path forward