-

More Than the Sum of Its Parts

A state-funded partnership between Mayo Clinic and the University of Minnesota has upped the ante in high-stakes biomedical research.

Stephen Brimijoin, Ph.D., a Mayo Clinic pharmacologist, discovered a surprising similarity between cocaine addiction and weight control.

He was using an enzyme mutated to break down cocaine faster. So, at least in mice and rats, a normally lethal dose of the drug is swept out of the bloodstream before it can reach the brain and cause euphoria, addiction or death. His hope is that the treatment might someday do the same for human addicts.

The elevated activity of this enzyme, known as butyrylcholinesterase, also decreased levels and effects of ghrelin, the hormone that causes hunger pangs. That discovery kicked off a new project exploring therapy to suppress hunger, treat human obesity and aid lifelong weight management.

Both projects, with Marilyn Carroll, Ph.D., a University of Minnesota psychiatrist, were undertaken with grants from the Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics, a state-funded research collaboration that supports joint Mayo-University research projects. The partnership grants provided a “stepping stone” to start the research and later attract greater outside funding, says Dr. Brimijoin.

“We certainly have benefitted by the Minnesota Partnership, which has helped us jump-start some high-risk ideas that turned out wonderfully. It would have been far harder to get it to happen if we hadn’t had this partnership funding to get us launched.”

The cocaine research later received a $5 million award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The obesity project continues under the Minnesota Partnership grant.

Dr. Brimijoin isn’t alone. Since the Minnesota Partnership was formed in 2003, it has provided state funding to Mayo and University of Minnesota researchers for more than 126 projects. That research has led to 50 patent filings, five issued patents and seven new licensed technologies.

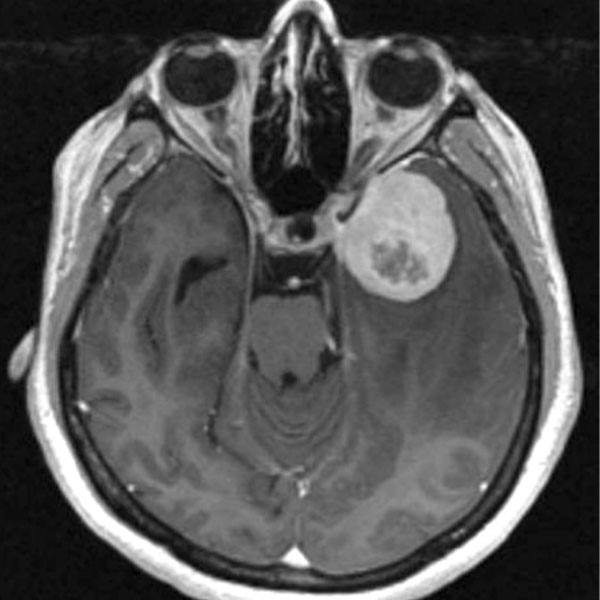

The first four projects funded by the partnership focused on atherosclerosis, prostate cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and diabetes and obesity. Since then, the range of projects has grown to include research on colon and pancreatic cancer, mesothelioma, brain tumors, drug addiction, transplant rejection, autoimmune diseases and infection prevention. Grants also have funded research on better pesticides for soybean aphids and a mobile lab in a truck to conduct obesity studies around the state.

“When there are things that are in the larger biotechnology sphere that aren’t necessarily medical genomics, we’re open to supporting those, as well, if they have a real connection to problems that are important in Minnesota,” says Eric Wieben, Ph.D., the Minnesota Partnership program director for Mayo.

Much of the program’s impact has occurred downstream. Projects begun with partnership funding have won 569 external grants, translating to more than $175 million from federal grant-making agencies, including more than $136 million from the National Institutes of Health. The NIH estimates that every $1 million it awards creates at least 16 jobs to support that research.

Partnership projects also have attracted some $15 million in philanthropic giving, $5 million in private industry investment, and more than $20 million in additional grants for infrastructure, such as facilities and equipment. That’s not bad, considering the partnership dollars allocated over 14 years total just over $132 million.

The Partnership has helped Mayo and the University combine forces to compete with the largest medical centers in the country to win research grants and make new discoveries in medical research and clinical care.

“Joining our forces together really emphasized the strengths we have in Minnesota,” says Mark Paller, M.D., senior associate dean of University of Minnesota Medical School. He notes that Mayo and the university have strong national reputations in medical research but says the partnership lifted their combined research efforts into the top five institutions in the country.

Origins

The Minnesota Partnership got its start as a spur-of-the-moment idea. Hugh Smith, M.D., former chair of the Mayo Clinic Rochester Board of Governors and founding member of what is now Mayo Clinic Health System, had just received a budget request from Mayo’s research group. They wanted to expand into the burgeoning field of genomics — reading the human genetic code to diagnose illness, predict disease, and fashion cures.

“It was clear we needed some space, and it was clear we needed some very, very expensive equipment,” Dr. Smith recalls. “Our databases were going to explode by factors of thousands. I was taken aback by all of these dollars and what we needed to do.”

Shortly after, at a meeting in the Twin Cities, Dr. Smith found himself seated next to Frank Cerra, M.D., the executive vice president and director of health sciences at the University of Minnesota. The two entities often competed for residents, fellows and patients, but, as they introduced themselves and shook hands, Dr. Smith recalls thinking, “Gosh, there’s got to be a way we might not compete but get together.”

So he said, “Frank, at the break, is there any chance you could talk?”

From that impromptu conversation, Drs. Smith and Cerra began meeting at a roadside diner to sketch out a plan — literally on napkins at first — for a cooperative research program. They rounded up support, first from Bob Bruininks, then president of the University of Minnesota, and later Gov.-elect Tim Pawlenty. And, to make sure their cooperative venture could win approval of federal grant-making agencies, they also met with Minnesota’s congressional delegation in Washington, D.C., and leaders of the NIH. Everyone was on board.

Gov.-elect Pawlenty was particularly supportive but warned that the state was still climbing out of a recession. In response, Drs. Smith and Cerra scaled back their request for state funds and proposed that Mayo and the university each put up $1 million and the state match it. “We put skin in the game, and all the state government has to do is match it. Pawlenty said, ‘I’ll do it.’” recalls Dr. Smith.

Dr. Smith says that he and Dr. Cerra agreed on two important principles from the start. First, only the best science would be funded. No grants would be based on politics. Second, no grants would be awarded to projects that could be done by either institution alone. To ensure that research is truly collaborative, eligible projects must have a principal investigator from Mayo and the university.

“That’s something that both Hugh Smith and Frank Cerra knew would ensure that this was more than just a paper collaboration activity,” says Dr. Wieben. “It’s worked out surprisingly well. It really has. It’s done good things for cross-fertilization between the two institutions in general.”

And Hugh Smith got the genomics infrastructure his researchers wanted. The Minnesota Legislature eventually appropriated $21.7 million to build a genomics research facility atop Mayo’s Vincent Stabile Building in Rochester for use by researchers under the auspices of the Minnesota Partnership.

Why it Works

The partnership made sense because Mayo and the university bring different strengths to the table.

“The whole was greater than the sum of the parts,” says Tucker LeBien, M.D., the partnership program director for the university. "If you looked at the research strengths of Mayo and the research strengths of the university, you could see where there were a lot of opportunities for real collaboration to pursue problems that quite frankly couldn’t be pursued at one institution or the other alone."

First of all, he says, the university could provide deep expertise in very basic genetics and biochemistry, as well as tremendous expertise in engineering. Mayo, on the other hand, had extraordinary clinical investigative infrastructure, databases and access to patient populations that the university could only dream about.

And then there’s the money.

“We give out really substantial awards, typically more than $1 million per project over two years,” says Dr. LeBien. “There’s no other internal grant program ─ either here or at Mayo ─ that even comes close to that level of support.”

Translational Products

An early goal of the partnership was the development of commercial products, such as medical devices and drugs. That effort has taken on new importance over the past several years with the creation of the Translational Product Development Fund administered by the partnership. It’s a separate source of state grant money to make new medical developments attractive to commercial investors. Awards can be as large as $400,000 over two years.

“It’s not funding to perform basic biomedical research. There are other funds within the partnership to do that,” says Andrew Badley, M.D., director of Mayo’s Office of Translation to Practice and coordinator of the Translational Product Development Fund. Instead, he says the projects they fund are to create a prototype of a new device, test a new device, optimize a drug candidate, test a drug candidate and enhance the commercialization potential of those products.”

And improving patient care is a goal everyone can get behind. Even in an era of hyper-partisan politics, politicians of all stripes have recognized the success of a partnership between the two biggest medical research institutions in the state. The Minnesota Legislature has incorporated the partnership into the state budget, reliably providing an average of $8.5 million a year for research grants.

“I think the Minnesota Legislature can be quite partisan from time to time, but everybody likes a feel-good story," says Dr. Wieben. "This is helping to keep Mayo and the university very competitive in this high-budget, fast-moving field.”

"What’s not to like?" he adds.

- Greg Breining, July 2018