-

MS or not MS? Mayo Clinic Neuroimmunology Lab answers the question

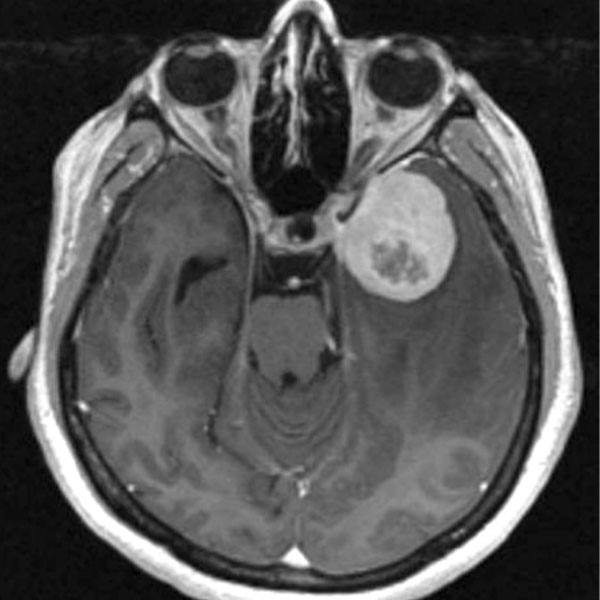

In 2017, Mayo Clinic launched a first-in-the-U.S. clinical test to help patients with some autoimmune disorders get the right diagnosis faster. The test defines a new form of inflammatory demyelinating disease, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) autoimmunity, which is distinct from multiple sclerosis (MS), with which it is commonly confused.

The test uses live cells to identify patients who are positive for an antibody to MOG. Mayo Clinic researchers have determined that patients who test positive for MOG antibodies usually don’t have classic MS, which has no biomarker. This is significant because, unless their disease is differentiated from MS, some patients have been treated with medications appropriate for MS but not for inflammatory demyelinating diseases such as neuromyelitis optica, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, optic neuritis and transverse myelitis. MS treatments have been reported to worsen the disease of patients with these other conditions. Correct and prompt diagnosis allows for early therapy with immunosuppressants rather than the disease-modifying agents used to treat MS.

From AQP4 to MOG-IgG

The new test allows serum detection of MOG-IgG (immunoglobulin), which targets a cell-surface protein present on oligodendrocytes in the brain. MOG-IgG is detected using a cell-based flow cytometry assay that measures a color signal transmitted by the IgG bound to MOG on living cells.

The AQP4 antibody, discovered at Mayo Clinic in 2004, was the first biomarker associated with inflammatory demyelinating diseases that could be used to distinguish MS from another neurodegenerative disease. Patients with AQP4 antibodies have an illness that resembles MS, but about 80 percent of them have been shown to have neuromyelitis optica.

The AQP4 antibody discovery led to redefining the diagnostic criteria — classifying neuromyelitis optica as a unique disease, not a variant of MS as previously thought. Having diagnostic-specific antibody tools allowed Mayo Clinic researchers to develop tests to help physicians rule out MS and for patients to get correct diagnoses in the early stages of disease.

Mayo Clinic now offers a comprehensive central nervous system demyelinating disease evaluation that includes both MOG antibody and AQP4 antibody tests. There is no overlap between the two antibodies in an individual patient. The combination of the two tests — AQP4 and MOG antibodies — allows for the most comprehensive evaluation for patients recently diagnosed with demyelinating diseases.

Both the MOG and AQP4 tests are available to Mayo Clinic patients and health care providers worldwide through Mayo Medical Laboratories, the global reference laboratory of Mayo Clinic.

“If a patient is positive for either, it tells the clinician something about the immunopathology of the disease and directs them toward a different type of treatment,” says neurologist Sean Pittock, M.D., co-director of Mayo Clinic’s Neuroimmunology Laboratory, and the Marilyn A. Park and Moon S. Park, M.D., Director of the Center for Multiple Sclerosis and Autoimmune Neurology. “We generally use immunosuppressant drugs to prevent attacks in both AQP4 and MOG-IgG-positive diseases. The traditional disease-modifying agents used to treat MS, such as interferon beta, may exacerbate these disorders, so correct and early diagnosis is important.”

Having diagnostic-specific antibody tools allowed Mayo Clinic researchers to develop tests to help physicians rule out MS and for patients to get correct diagnoses in the early stages of disease.

From antibody discovery to test development

This pioneering work emanates from Mayo Clinic’s Neuroimmunology Laboratory, part of the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology. The lab discovers antibodies and validates antibody tests to clarify differences among autoimmune diseases in a blossoming specialty led by Mayo Clinic. In fact, the specialty appellation was coined by Mayo Clinic.

The lab was founded in 1981 by Vanda Lennon, M.D., Ph.D., immunologist and the Dorothy A. Adair Professor. Dr. Lennon was instrumental in developing the field of autoimmune neurology and leading many of the laboratory’s discoveries. Today the lab is co-directed by Dr. Pittock, and Andrew McKeon, M.D. , M.B., B.Ch.

The Neuroimmunology Lab’s work includes:

- Developing novel biomarkers and packaging them into disease-specific profiles and categories (e.g,. autoimmune epilepsy, encephalopathy and autoimmune dysautonomia evaluations).

- Establishing an Autoimmune Neurology Clinic in 2006 to evaluate patients. The clinic is staffed by five neurologists focused on autoimmune disease.

- Starting drug trials based on biomarkers discovered at Mayo Clinic (e.g., eculizumab in neuromyelitis optica [NMO] and intravenous immunoglobulin [IVIg] in autoimmune epilepsy).

- Training the next leaders in the field through the first autoimmune neurology fellowship program in the U.S. — a program that has produced 14 autoimmune neurologists since 2006. Some have stayed at Mayo Clinic; others now lead similar programs in the U.S. and internationally.

- Discovering GFAP and MAP1b antibodies — novel biomarkers of encephalitis — in 2017.

- Developing first-in-U.S. test to detect antibodies to the MOG protein. Studies from Mayo Clinic indicate this disease is twice as common as AQP4-IgG-associated diseases and affects about

1 million people.

“Over the past decade, there has been an explosion, driven by technological advances, in the number of neural antibody biomarkers,” says Dr. Pittock. “These antibodies help physicians diagnose autoimmune neurological disorders, direct them toward specific cancer types and assist in therapeutic decision-making. As more antibodies become available to test, it is more challenging for general neurologists and physicians to keep up with this rapidly changing field.

“Our laboratory is committed to offering comprehensive, clinically relevant neural auto-antibody profiles to assist clinicians in providing optimal care to their patients, especially when an autoimmune etiology is in the differential diagnosis.”

This article originally appeared in Mayo Clinic Alumni Magazine, Issue 2, 2018.

###