-

Featured News

New therapy improving lives of patients with neuroendocrine tumors

For some patients neuroendocrine tumors lead to diarrhea or pain, while others will have no symptoms and the tumors are only discovered during an imaging exam for another issue. But now a new treatment option is available to help manage these symptoms.

Watch: New therapy improving lives of patients with neuroendocrine tumors.

Journalists: Broadcast-quality video (3:52) is in the downloads at the end of this post. Please "Courtesy: Mayo Clinic News Network." Read the script.

It started subtly. There was no sign anything was amiss — just some itching and rashes developing on both of Jay Elsten’s legs.

A trip to his primary care physician in 2012 led to an initial diagnosis of hepatitis, a prescription for antibiotics and a recommendation to call again if Elsten were not feeling better in a few days.

“Well, in three days I couldn’t keep anything down. I’d lost 40 pounds in a week, and [my doctor] said to go to the ER,” Elsten says.

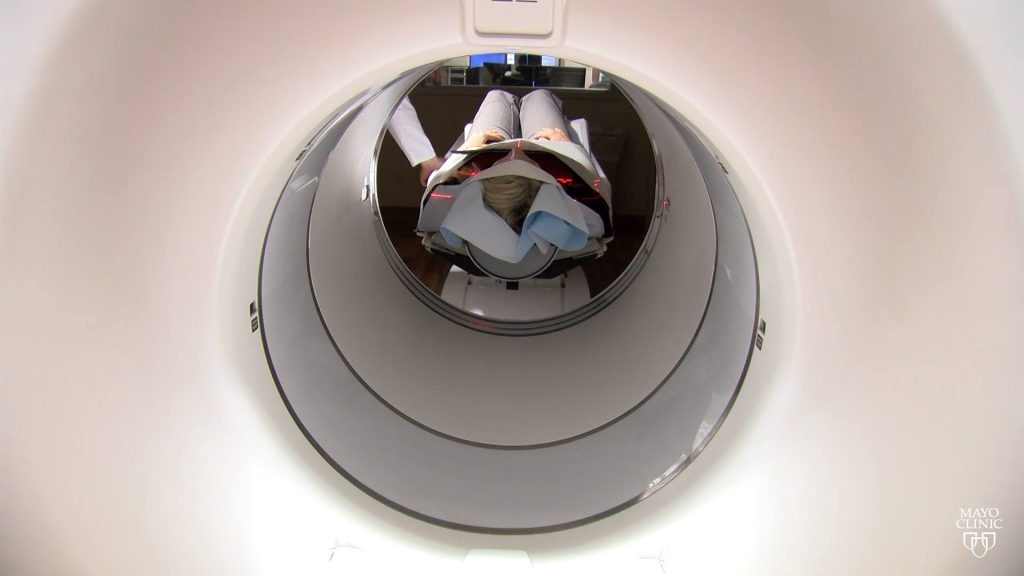

This led to more tests, including a CT scan, and the location of a tumor on his pancreas — either adenocarcinoma or neuroendocrine — and a decision of where to go next.

“It was too rare what I had. [My doctor] gave me three choices,” Elsten says. “The business I was in before, I had dealings with people in Dodge Center [Minnesota], so I knew people up here. And I thought, ‘I’ll go to Mayo because if I get in trouble, I know people up there that can help my wife.’”

A biopsy at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, revealed that Elsten had a neuroendocrine tumor in his pancreas.

“Neuroendocrine tumors are really a collection of tumors that can arise anywhere, essentially, in the body,” says Dr. Thorvardur Halfdanarson, a Mayo Clinic medical oncologist. “Not only can they arise anywhere in the body, but they behave very differently from one person to the next.”

The tumors’ presentation in patients is so unique that some will experience diarrhea or pain from the tumors, while others will have no symptoms and the tumors are discovered during an imaging exam for something else, Dr. Halfdanarson says. Some tumors are slow-growing, others are aggressive.

Neuroendocrine tumors can secrete hormones, which are the source of many of the symptoms that patients experience, Dr. Halfdanarson says.

He adds, “They are still a big enigma, and for the most common ones, the small bowel neuroendocrine tumors, we really don’t have a good understanding why people get them.”

Treatment options vary, as well, with surgery, chemotherapy and nuclear medicine therapy among the options.

Once he had a diagnosis, Elsten had clarity. “I was here to fight it from the beginning and it’s what I intend on doing,” he says.

“You know, I want to see my kids graduate. I want to walk my daughter down the aisle. You know, I intend on staying around for a long time,” adds Elsten, who is married and has two children.

And it has been a battle.

A multidisciplinary team comprising medical oncology, gastroenterology, pulmonary medicine, surgery, radiology (especially nuclear medicine) and pathology has supported Elsten through each round.

“The care plan never changes. Where other places, you get a new doctor, they’ve got a different idea,” Elsten says. “They decided from the beginning what they were going to do, and that’s the same plan that we’ve carried out through the whole seven years.”

His medical oncology team started him on chemotherapy, which shrank the cancer and gave him two years without issues. And then the cancer had spread to his liver. This time, chemotherapy was not effective in bringing his neuroendocrine tumors in check, and another option was needed.

In January 2018, the right treatment was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for clinical use in treating gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: lutetium Lu 177 dotatate, a peptide receptor radionuclide therapy, also called PRRT.

“It’s kind of a ‘Trojan horse,’” says Dr. Geoffrey Johnson, chair of the Division of Nuclear Medicine, adding that the dotatate binds to receptors on the cancer cells and the lutetium radiates the cells, killing them.

“PRRT … is a therapy using a radioactive compound that sticks to the neuroendocrine tumor cells,” Dr. Halfdanarson says. “There are three components to it. There is what’s called a somatostatin analog, which binds to the receptors of the tumor cells, and then there is therapeutic radionuclide or radioactive molecule, which is therapeutic. And then there is almost like a glue that binds these things together.

“So we inject this into a vein that circulates around the body, and it sticks to the tumor cells that express the somatostatin receptors … and then this radiation molecule sits right on the tumor cell and kills the tumors cells with radiation,” he says.

The Division of Nuclear Medicine, part of the Department of Radiology, is a key player in diagnosing neuroendocrine tumors through PET imaging, and is part of the nuclear medicine therapy program, preparing and administering the radioactive drugs.

PET imaging, with gallium Ga 68 dotatate, identified Elsten as an ideal candidate for lutetium Lu 177 dotatate. Patients receive four doses, each eight weeks apart, with checkups about a month after each infusion. For most patients, improvement in symptom management comes after the second dose, Dr. Halfdanarson says.

Elsten says Mayo Clinic has given him added years — which has opened the door to new therapies.

“The longer I can push this disease off, things change. You know, there are new treatments. There are all kinds of things, and [lutetium Lu 177 dotatate] is something that didn’t exist seven years ago here whenever I was first diagnosed,” he says.

And for Elsten, the effects of this new treatment were almost immediate. Though his response was atypical, he says he is grateful.

“Dr. Halfdanarson told me before I got the first treatment, he said, ‘Don’t expect immediate results. It usually takes two rounds before we see anything.’ And it was just amazing,” Elsten says. “Within three or four days, the diarrhea stopped. It had shocked the tumor enough … it quit producing that hormone, and within a week I was back to normal. It was simply amazing.”

Rachel Eiring, a medical oncology physician assistant, has been part of Elsten’s care team during his lutetium Lu 177 dotatate treatments, and was surprised at the results after the first infusion.

“I think what’s absolutely remarkable about his story is the huge improvement in his quality of life,” she says. “He went from … being in and out of the hospital, more days in the hospital than not, because of severe diarrhea and electrolyte abnormalities … to being able to do the things that he wanted. So that was really kind of exciting to see somebody have such a big impact following just his first treatment.”

“It’s been a great experience up here,” Elsten says. “When I was in the hospital in Joplin with all this, there was a patient in there, and one of the nurses asked me if I would go talk to him about Mayo. … I said I’d be happy to. You know, I’m happy to talk to anybody about Mayo. My family knows it. They probably get tired of hearing about it. But, you know, everything runs so much different here than it does at home, and it’s just an amazing place.”

###

About Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit organization committed to innovation in clinical practice, education and research, and providing compassion, expertise and answers to everyone who needs healing. Visit the Mayo Clinic News Network for additional Mayo Clinic news and An Inside Look at Mayo Clinic for more information about Mayo.

Media contact:

- Ethan Grove, Mayo Clinic Public Affairs, 507-284-5005, newsbureau@mayo.edu