-

Ovarian cancer: New treatments and research

Editor's note: May 8 is World Ovarian Cancer Day.

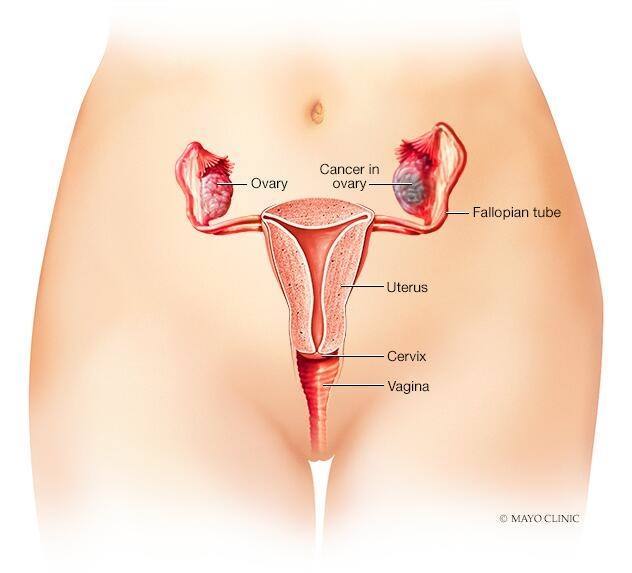

Three cancers — ovarian epithelial cancer, fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer — are commonly called ovarian cancer. They arise from the same kind of tissue and are treated similarly.

"The ovaries and fallopian tubes are so anatomically close to each other that we sometimes can't tell if the cancer is coming from the ovary or the fallopian tube," says S. John Weroha, M.D., Ph.D., a Mayo Clinic oncologist and chair of Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center's Gynecologic Cancer Disease Group. "When we diagnose patients with primary peritoneal cancer, I explain that under the microscope, and in the pattern of spread through the body, it looks like ovarian cancer even though the ovaries are not involved."

Primary peritoneal cancer forms in the peritoneum, the tissue that lines the abdominal cavity and the organs within it. Fallopian tube cancer forms in the tissue lining the inside of the tubes that eggs travel through to move from the ovaries to the uterus.

About 85% to 90% of ovarian cancers are ovarian epithelial cancers, also known as epithelial ovarian carcinomas, which form in the tissue lining the outside of the ovaries.

Dr. Weroha says new treatments are helping more people survive ovarian cancer of all types, and researchers are studying new treatments and screening methods in clinical trials. If you've been diagnosed with ovarian cancer, he wants you to know there is hope. Here's why:

New targeted therapies are improving survival.

Surgery and chemotherapy are no longer the only options for ovarian cancer treatment. Targeted therapies use drugs to target and attack cancer cells. These include monoclonal antibodies and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, or PARP, inhibitors.

Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are molecules engineered in the laboratory to find and attach to specific proteins associated with cancer cells. Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody used with chemotherapy to treat ovarian cancer recurrence by preventing the growth of new blood vessels that tumors need to grow.

Researchers are combining bevacizumab with new drugs to improve outcomes. One example is a monoclonal antibody recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) called mirvetuximab soravtansine for people with ovarian cancer recurrence. This drug is used when a person's cancer was previously treated with at least one systemic therapy to target a protein called folate receptor alpha.

"Ovarian cancers have many folate receptors. Most normal cells don't," says Dr. Weroha. "This drug is an antibody that has chemotherapy stuck onto it. Think of it as a guided missile traveling the body and sticking to cells with folate receptors. In patients whose ovarian cancer has recurred and whose tumors have many folate receptors, mirvetuximab soravtansine can shrink tumors far better than any other therapy. The response rate is about double what you see with any other treatment."

PARP inhibitors

PARP inhibitors are drugs that block DNA repair, which may cause cancer cells to die. Olaparib is an example of a PARP inhibitor used to prevent recurrence in people with ovarian cancer whose tumors have BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations. Research has shown that olaparib can significantly improve survival without recurrence in people with this diagnosis. "This is a front-line treatment, which means this is part of the first treatment regimen patients receive when they are newly diagnosed," says Dr. Weroha.

A vaccine may one day be used to fight ovarian cancer.

Matthew Block, M.D., Ph.D., a Mayo Clinic medical oncologist, and Keith Knutson, Ph.D., a Mayo Clinic researcher, are developing a vaccine to prevent ovarian cancer tumors from returning in people with advanced ovarian cancer whose tumors have recurred after surgery and chemotherapy.

White blood cells are extracted from a blood draw and manufactured to become dendritic cells — immune cells that boost immune responses. These cells are returned to the patient in vaccine form to trigger the immune system to recognize and fight the cancer.

The vaccine will be given in combination with an immunotherapy drug called pembrolizumab to identify and kill any tumors that don't respond to the dendritic cells.

"Pembrolizumab is in a category of drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors," says Dr. Weroha. "This drug is designed to release the brakes on the immune system to allow it to do what it naturally wants: kill things it doesn't like. The hope is that the vaccine combined with the immunotherapy drug will kill a lot of ovarian cancer. It's exciting research."

A screening test may be on the horizon.

There is no screening test for ovarian cancer, but Jamie Bakkum-Gamez, M.D., a Mayo Clinic gynecologic oncologist, is hoping to change that. She and her research team discovered that methylated DNA markers could be used to identify endometrial cancer through vaginal fluid collected with a tampon. Eventually, this same science could extend to ovarian cancer.

Methylation is a mechanism cells use to control gene expression — the process by which a gene is switched on in a cell to make RNA and proteins. When a certain area of a gene's DNA is methylated, the gene is turned off or silenced, indicating that a gene is a tumor suppressor. The silencing of tumor suppressor genes is often an early step in cancer development and can suggest cancer.

Dr. Bakkum-Gamez and her colleagues developed a panel of methylated DNA markers that could distinguish between endometrial cancer and noncancerous tissue in vaginal fluid. Based on this research, she hopes to develop an affordable tampon-based home screening test for endometrial, ovarian and cervical cancers, as well as high-risk HPV.

"This is exciting because this type of screening test can be used by people living in rural areas,” says Dr. Weroha. “If it's successful, it could help healthcare professionals identify ovarian and other gynecologic cancers sooner, when they're more treatable, in people living in all the communities we serve.”

A gynecologic oncologist and clinical trials can help you get the best possible treatment.

If you've been diagnosed with ovarian cancer, Dr. Weroha recommends making an appointment with a gynecologic oncologist. "A gynecologic oncologist will be up to date on the current treatment recommendations and the management of side effects. That's important," he says. "Once the plan is set, however, any medical oncologist could implement it.”

Dr. Weroha also recommends newly diagnosed patients ask their care teams if they are candidates for PARP inhibitors, mirvetuximab or clinical trials. "PARP inhibitors and mirvetuximab are newer treatments that could influence the outcome of your overall treatment. Always ask about clinical trials because when ovarian cancer recurs, there is no treatment so good that we can stop looking for something better," he says. "There is a very realistic hope that if your cancer were to come back, we would have something better that we don't have today."

This article originally published on the blog of the Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center.