-

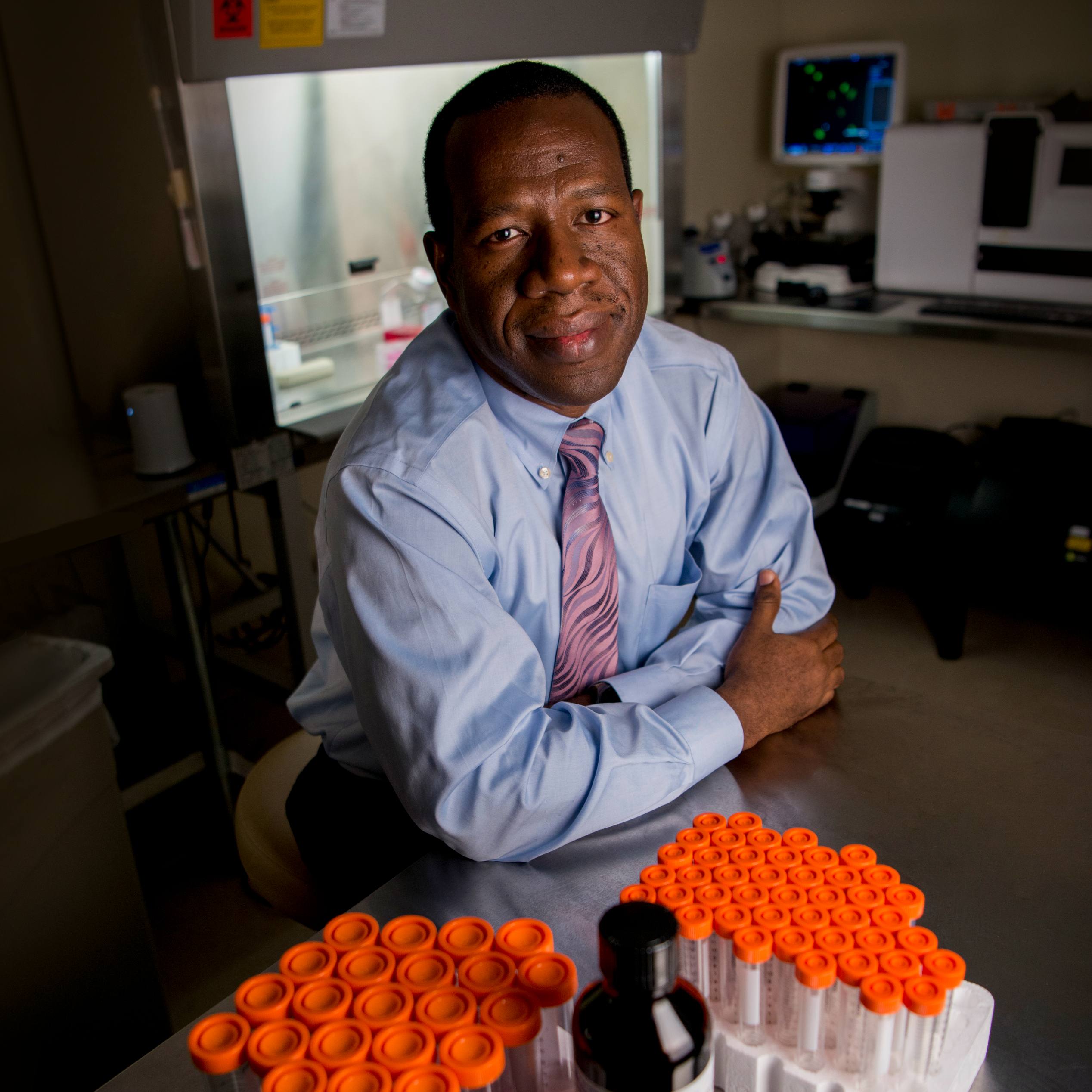

Pushing the limits of gene therapy for osteoarthritis

For more than twenty-five years, Christopher Evans, Ph.D., a Mayo Clinic orthopedic scientist, has pushed to expand gene therapy beyond its original scope of treating rare single-gene defects. Not everyone has been easily convinced. When he submitted one of his first federal grants to pursue gene therapy for arthritis, one of the reviews scoffed at the notion, quoting the Latin Primum non nocere: first do no harm.

"It then went on to say that gene therapy is dangerous and should only be used for genetic diseases," Dr. Evans, who directs Mayo's Rehabilitation Medicine Research Center, recalls. "I ran into that sentiment a lot."

But gene therapy has come a long way, as researchers have meticulously developed safer and more effective ways to use genes as medicine. Several gene therapies have already been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and experts predict that over the next decade 40 to 60 more will be approved for a variety of indications. Dr. Evans hopes one of those indications will be for osteoarthritis, a form of arthritis that affects over 32.5 million U.S. adults. In osteoarthritis, the cartilage that cushions the ends of bones – and sometimes the underlying bone itself – degenerates over time. It is notoriously difficult to treat.

"Any medications you inject into the affected joint will seep right back out in a few hours," says Dr. Evans. "As far as I know, gene therapy is the only reasonable way to overcome this pharmacologic barrier, and it’s a huge barrier."

By genetically modifying cells in the joint to produce their own pharmacy of anti-inflammatory molecules, Dr. Evans aims to engineer knees that are more resistant to wear and tear.

The Evans laboratory found that a molecule called interleukin-1 (IL-1) plays an important role in fueling inflammation, pain, and cartilage loss in osteoarthritis. Conveniently, the molecule had a natural inhibitor, aptly named the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), that could form the basis of the first gene therapy for the disease.

In 2000, Dr. Evans and his team packaged the IL-1Ra gene into an adeno-associated virus, a relatively harmless carrier that is already present in most of the human population. They tested the viral vector in cells and then — for 15 years — in a range of animal models, including in horses. The results were encouraging. His collaborators at the University of Florida, where the testing in horses took place, showed that the gene therapy successfully infiltrated the cells that make up the synovial lining of the joint as well as the neighboring cartilage. That cartilage was protected from breakdown, and the horses became less lame. In 2015, the team got investigational new drug approval to start human testing. But manufacturing challenges kept them from injecting their first volunteer for another four years.

In May 2021, Dr. Evans presented interim results of the phase I trial at the annual meeting of the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy. The study demonstrated the safety of the therapy, prompting the FDA to approve a phase II trial to evaluate its effectiveness. Even as Dr. Evans advances this application through clinical trials, he is also considering gene therapy for regenerative medicine, to rebuild the bone and cartilage damaged by arthritis or even the nerves severed by spinal cord injury.

"I can write down a whole list of other applications — including COVID-19 — but I try to constrain myself because I don’t want to spread myself too thin," he says. "There’s no end to the things you can do with this technology once you get going."

- Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., April 14, 2022

Mayo Clinic and Dr. Evans have a financial interest related to the potential treatment referenced in this article.