-

Gastroenterology

Reducing the panic of fecal incontinence

Imagine the distress of waiting in a stalled checkout line, the bathrooms at the back of the store, when your bowels begin to rumble and you have the uncontrollable urge to go. For those with fecal incontinence, panic ensues at the very thought of being caught unprepared at moments like these. They know the urgency to defecate can strike at any time, and they may not be able to stop it.

Fecal incontinence is the inability to control bowel movements, causing stool to leak unexpectedly from the rectum. In the worst cases, fecal incontinence can lead to a complete loss of bowel control. It's an uncomfortable and often embarrassing topic, but the crippling fear it instills leaves many people desperately seeking answers.

Adil E. Bharucha, MBBS, M.D., a Mayo Clinic gastroenterologist in Rochester, Minn., hears too many stories from his patients, mainly women, about the panic created by fecal incontinence — the condition is not unknown in men but is much more common in women.

Prevalence and causes

In 2001, Dr. Bharucha received a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study the epidemiology and mechanisms of fecal incontinence. Before his collaboration

with Mayo Clinic epidemiologist L. Joseph Melton III, M.D., and statistician Alan R. Zinsmeister, Ph.D., both of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Dr. Bharucha was unclear about the prevalence of fecal incontinence.

Together, they developed a questionnaire that was sent to 5,300 women in Olmsted County, Minn., with 2,800 responding. The study, whose results were published in Gastroenterology in May 2005, found that 1 in 10 women in the community had fecal incontinence, and that the prevalence increases with age.

A decade ago, fecal incontinence in women was thought to have resulted from injury to the sphincter that occurred as a woman gave birth. Dr. Bharucha observed, however, that most of his patients did not experience symptoms until decades after delivery. He wondered if factors other than trauma during childbirth might be the cause of fecal incontinence.

The Rochester Epidemiology Project — a geographical medical repository in Olmsted County — has maintained a common medical record with its affiliated hospitals and other county health care providers, including Mayo Clinic, for close to a century, making it the ideal tool to look back on decades of obstetrical history and possibly answer the question: To what extent does obstetric trauma cause fecal incontinence in women who develop the problem decades after vaginal delivery?

Dr. Bharucha designed a study to answer that question. At night after regular work hours, he called the women whom the questionnaire identified as having fecal incontinence, encouraging them to participate in the study. His determination paid off, as 88 percent agreed.

"If any study was going to solve the question, this was it," Dr. Bharucha says. "We invited 200 women with fecal incontinence, plus 200 age-matched women without it, in to see us."

Observations from the survey and decades of obstetrical records from the Rochester Epidemiology Project, combined with the rigorous study, showed that rectal urgency and diarrhea, rather than obstetric trauma, are the main risk factors for fecal incontinence among women. The work was published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology in 2006.

The discovery that bowel disturbances are a significant risk factor for fecal incontinence highlighted the importance of managing the disturbances through noninvasive treatments. Dr. Bharucha subsequently developed and validated a fecal incontinence assessment scale that is increasingly used by physicians and researchers, as reported in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology in 2006.

Dr. Bharucha also knew that he needed better diagnostic tools to identify and assess anorectal function if he hoped to help women with fecal incontinence. With that goal, he set about building an extensive network of collaborators both within Mayo Clinic and externally.

MRI: Visualizing pelvic floor motion in real time

Thunderstruck, Dr. Bharucha's eyes widened as he read an ultrasound report stating that the image could not distinguish whether the anal sphincter was completely normal or completely torn. Already frustrated with the limitation of tests to assess anorectal function, Dr. Bharucha wondered if there might be a better way to assess the function. He went running with the report to his radiology colleagues.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) now acquires images fast enough to visualize blood flow in the aorta and the renal vessels. Dr. Bharucha asked his colleagues if this diagnostic test could be adapted to observe pelvic floor motion in real time, an observation crucial to determining anorectal function.

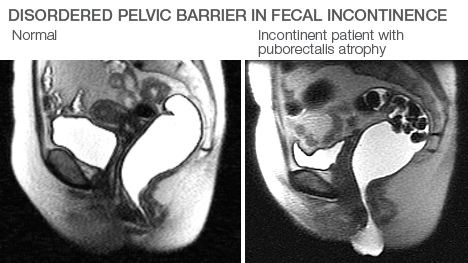

The pelvic floor, sometimes called a pelvic diaphragm, is made up of several muscles that span the area under the pelvis and support the rectum like a hammock. The body uses these muscles in the maintenance of anorectal function. When these muscles aren't performing properly, fecal incontinence can occur.

Armed with an NIH grant to investigate anorectal dysfunction in women, Dr. Bharucha approached radiologist Joel G. Fletcher, M.D., of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, about developing a better test for dynamic pelvic floor imaging. With crucial participation of Mayo Clinic biomathematician Armando Manduca, Ph.D., who developed the first dedicated software program to analyze pelvic floor motion, they were successful in developing a type of MRI known as magnetic resonance proctography (MRP), and results were published in 2003 in the American Journal of Gastroenterology. MRP is now a standard clinical test at Mayo Clinic.

MRE: Testing sphincter elasticity

Although magnetic resonance proctography works well as a diagnostic test for many patients, it is limited in its ability to detect any physical deformity in some sphincters with weak pressure. Weak pressure in the anorectal muscles can lead to fecal incontinence. In these cases, magnetic resistance elastography (MRE) shows more promise.

Magnetic resistance elastography is an application of MRI that searches out stiff tissue, which can occur in scars and tumors. The stiff tissue can be a contributing factor to weak pressure in the sphincter.

Dr. Bharucha likens an MRE scan to dropping a pebble in a pond. A probe, like the pebble, sends subtle vibrations through the sphincter, producing mechanical waves. The rate at which they spread reveals its elasticity. The less elastic the sphincter muscles are, the more likely is the occurrence of fecal incontinence.

Along with Drs. Fletcher and Manduca, the Mayo Clinic MRE team includes radiology researcher Joel P. Felmlee, Ph.D., and technicians Phillip J. Rossman, Roger C. Grimm and Scott A. Kruse. This is Dr. Bharucha's dream team for finding better ways to apply MRE technology to the difficult task of diagnosing the cause of fecal incontinence.

"The ideas bounce back and forth so fast that I often have to ask them to please stop and explain what they just said," Dr. Bharucha says with a laugh. "We have been working doggedly to overcome the unique challenges of doing MRE of the sphincter — it is inaccessible, has a very thin structure, and the waves that form are distorted rather than propagating in one direction."

Although the team has successfully produced images that reveal the function of the sphincter and the location if there has been an injury, MRE imaging of the sphincter isn't ready yet for regular clinical use.

Other innovations follow

Because much is known about the mechanical properties of the lung, Dr. Bharucha connected with Mayo Clinic pulmonary specialist Rolf D. Hubmayr, M.D., who suggested experimenting with sinusoidal waveforms to measure stiffness in anorectal muscles, as has been done in airway muscles in rodents. Studies were successful in adapting the technique to measure the rate of distention in the colon and rectum, as reported in 2001 in the American Journal of Physiology - Gastroenterology and Liver.

"When the rectum is rapidly distended it responds by contracting, causing urgency," Dr. Bharucha says. "However, while urgency normally subsides when defecation is inconvenient, if the rectum is abnormally stiff it may not respond in time to prevent leakage."

After his collaboration with Dr. Hubmayr, Dr. Bharucha approached Randolph W. Stroetz, R.R.T., a respiratory care technician at Mayo Clinic Hospital — Rochester, for help developing the first portable anorectal manometer to measure pressures in the rectum and anal canal. The portable anorectal manometer became one more diagnostic tool for Dr. Bharucha to use when assessing the causes for fecal incontinence.

In 2012, the Food and Drug Administration approved the portable anorectal manometer, for which Dr. Bharucha and Stroetz share a pending patent. This inexpensive, simple device is accessible to general practitioners. It is licensed to Medspira, a company in which Mayo Clinic has shares.

Nerve damage also can cause weakness in anorectal muscles. To improve the test for anal sphincter nerve injury, Dr. Bharucha recruited Mayo Clinic neurologists Charles (Michel) Harper Jr., M.D., Jasper R. Daube, M.D., and William J. Litchy, M.D., to explore anal electromyography (EMG). They developed a more accurate test, reported in a 2005 issue of the journal Gut, and identified anal sphincter nerve injury in 50 to 60 percent of women with fecal incontinence, a much higher percentage than previously thought.

Adding it all up

Close interaction between Dr. Bharucha and his Mayo Clinic colleagues Michael Camilleri, M.D., Gianrico Farrugia, M.D., and Joseph H. Szurszewski, Ph.D., all gastroenterology researchers, has earned international acclaim for Mayo Clinic's Gastrointestinal Motility Clinic. The clinic is the first center nationwide to introduce high-resolution anorectal manometry into clinical practice and to develop normal values and a system with which to classify patients with defecatory disorders, including fecal incontinence, as reported in the American Journal of Gastroenterology and Gastroenterology.

The Gastrointestinal Motility Clinic now offers a panel of tests to assess rectal stiffness, sphincter strength and urgency. This comprehensive approach provides an array of sophisticated diagnostic tools to help researchers zero in on the cause of fecal incontinence in each patient.

"Most of my collaborators had never considered working in my field," Dr. Bharucha says. "I am very grateful for their enthusiasm and expertise once they understood how common and distressing these disorders are. People say that the beauty of collaborating is that you work with smarter people. In my case, it's really true."