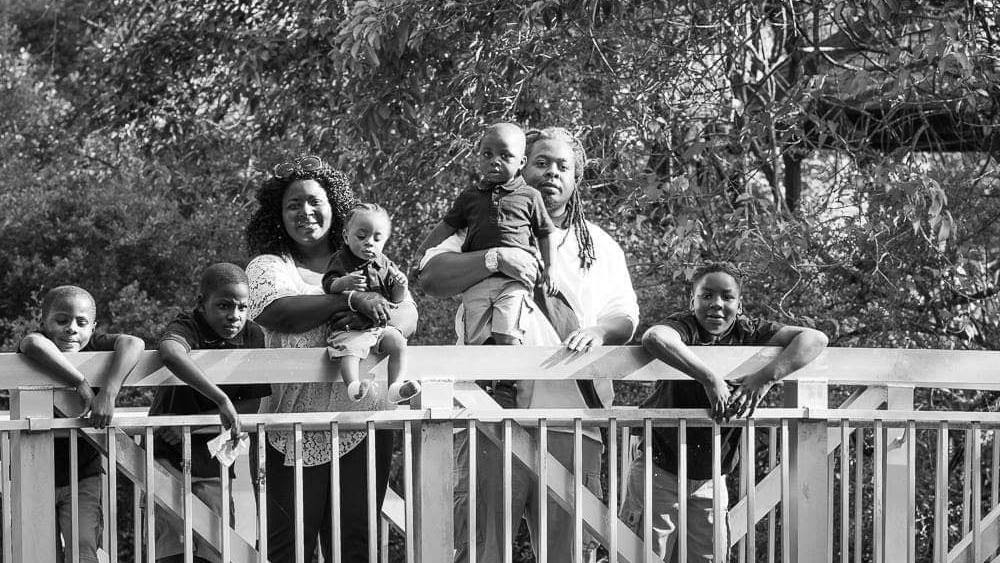

Family is everything to Felicia Curtis. The mom of five from Gainesville, Florida, knew she had to fight when she was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in 2017, when she was 20 weeks pregnant with her youngest child.

Over the next several months, Felicia underwent several rounds of chemotherapy to fight the cancer. Her son was born healthy at 33 weeks. The future was bright.

But six months later, the cancer returned, and doctors said the outcome was grim.

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma accounts for about four percent of all cancer diagnoses in the United States. According to the American Cancer Society, over 81,000 people are diagnosed annually with the disease and more than 20,000 will die from it.

Doctors in Gainesville recommended Felicia move her care to Mayo Clinic, which has an extensive bone marrow transplant program.

In August 2019, after meeting with Ernesto Ayala, M.D., a Mayo Clinic hematologist and oncologist who specializes in caring for patients with cancers like hers, Felicia underwent an autologous bone marrow transplant. The procedure uses healthy blood stem cells from a patient's own body to replace diseased or damaged bone marrow.

For a short time, Felicia thrived. But the cancer was relentless.

"But I believed I was meant to be here to raise my family," she adds, noting her confidence in her Mayo Clinic care team.

Felicia's body was weak from the cancer and the effects of the first transplant. But Dr. Ayala told Felicia he had a plan. He suggested a second transplant ― an allogeneic stem cell transplant that relies on healthy cells from a donor.

There was only one challenge: Felicia is African American, and diverse patients can face challenges finding a donor.

"The biggest challenge that we have to finding donors to proceed with bone marrow transplantation is ethnicity," says Dr. Ayala. "Only about 20% of all minority patients find a match."

Siblings and parents are sometimes matches. Otherwise, a match may be found in the national bone marrow donation registry. The problem is most people registered as donors are white.

"The most important factor when we look for a donor is HLA matching. HLA stands for human leukocyte antigens, which essentially are just markers in the surface of the cells," says Dr. Ayala. But having the most optimal match means a better chance at success.

In Felicia's case, family members were screened first and then ruled out. A search of the national bone marrow registry revealed only partial matches.

Felicia began educating people and encouraging friends and others to be screened as bone marrow donors ― if not for her then to help someone else.

"There is a lack of knowledge and understanding about what it is to register and to be a donor, and how it can affect a lot of lives by you just doing one selfless act," shares Felicia.

She got a call in August 2020 that a match had been located. It was exactly one year from the day of her first transplant.

Although the donor remains anonymous, Felicia learned her cells came from a 23-year-old African American. "She's my angel," says Felicia. "Not only did she save my life but the lives of my family. I hope to meet her one day and for my family to meet her."

Today, Felicia celebrates life in remission. She is back at work and enjoys spending as much time with her children as possible. She is also working toward opening her own business to help minority women who need wigs.

"There are no wigs out there for minority cancer patients that are small enough to fit the head and look realistic. My vision is to make it more comfortable for them," she says.