Jennifer Summers, 35, is an optimistic, articulate woman. She enjoys crafting, spending time with her close-knit family, and leading small groups and organizing volunteers at her church. And she is excited that she can carry a 32-ounce water bottle. This may not feel like an important feat to some people, but it's momentous for Jennifer and others diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy.

Official diagnosis

As a child, Jennifer seemed to struggle with movement.

"I started having trouble when I was about 9," she says. "I was very clumsy, and had trouble running or climbing stairs. I also had a lot of pain, like growing pains, except I didn't grow that much."

For years, Jennifer had unanswered questions, inaccurate and nonspecific diagnoses. When she was 14, she and her family moved to Holmen, Wisconsin, and Jennifer was evaluated at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. After several appointments and tests, the family found out what was causing her pain, troubles with movement and loss of function. At 16, Jennifer was diagnosed with type III spinal muscular atrophy.

Spinal muscular atrophy is a disease that damages nerve cells in the spinal cord called motor neurons. This damage gets worse, and muscles lose strength over time. The disease can affect actions like sitting, walking, swallowing and breathing. It is passed on to children by parents through abnormal genes. About 1 in 50 people are genetic carriers, and about 1 in 10,000 babies in the U.S. is born with spinal muscular atrophy.

People with type III spinal muscular atrophy have normal life spans, but they typically require a wheelchair due to progressive weakness and breathing support later in life.

Jennifer and her family found hope in having a diagnosis, but they could do little to stop her muscle and nerve damage progression.

"At that time, there were no treatments available," says Jennifer. "We focused on managing the complications of nerves and muscles dying and getting adaptive equipment."

New treatment option

Over the next 18 years, Jennifer's muscles continually got weaker and she required an electric wheelchair to move around. In 2016, a new treatment for spinal muscular atrophy was approved by the FDA. This treatment involves injecting a medication called nusinersen (Spinraza), directly into the spinal fluid of patients with spinal muscular atrophy.

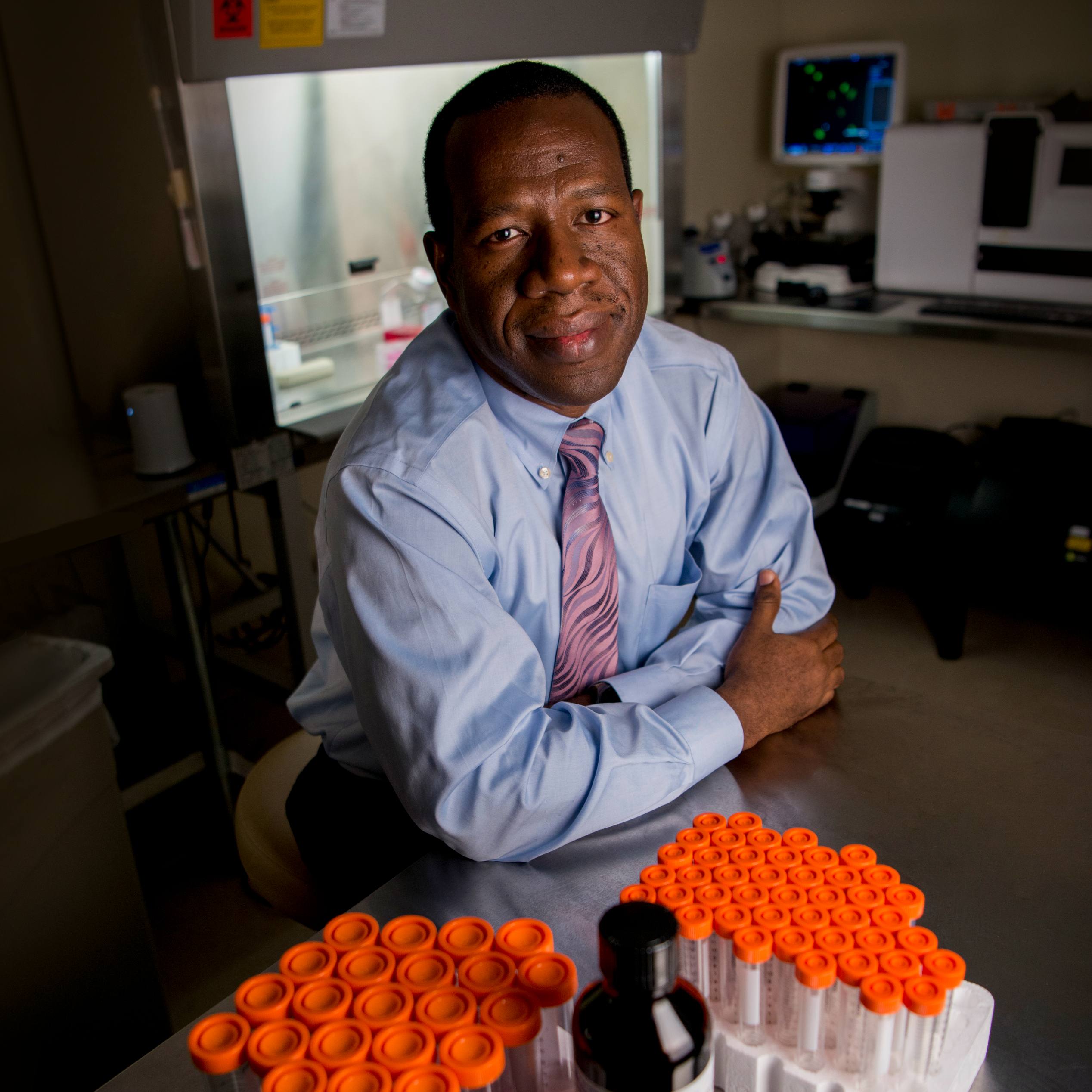

"This treatment alters the way that proteins are made in the body," says Daniel Anderson, D.O., a neurologist and neuromuscular specialist at Mayo Clinic Health System in La Crosse. "In this disease, there is an absence of a specific protein. The treatment alters the way that a specific protein is made and takes a bad protein and changes it into a functional protein."

In 2019, Jennifer met Dr. Anderson and his team for the first time. She was surprised to learn that he had completed advanced training during his fellowship in the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy with nusinersen (Spinraza) injections.

"Before I got into his office, he was ordering tests to see if I could handle the Spinraza treatments," says Jennifer, "At our first meeting, he was like 'So do you want to get treatment for your SMA (spinal muscular atrophy).' I was surprised. I told him 'Yeah, I would really like that.'"

"This type of rare disease wouldn't be traditionally taken care of in community settings, especially with complicated treatment regimens," says Dr. Anderson. "At Mayo Clinic Health System, we have subspecialists who are familiar with rare genetic diseases, and that, along with our connection to Mayo Clinic in Rochester, gives us the opportunity to care for patients with complicated needs and treatment regimens closer to their homes."

After six months of additional tests and waiting for insurance approval, Jennifer received her first nusinersen injection in December 2019. The medication was injected into her spinal fluid, similar to an epidural placement during labor or surgery. Each treatment takes about one to two hours and occurs every four months.

Improved strength

After her first couple of treatments, Jennifer noticed changes in her upper body strength and motion. One tangible way she gauged improvement was by the amount of weight she could hold away from her body and support, measured by water bottle size. She had been using a 12-ounce bottle, but she was able to progress to a 16-ounce bottle after her treatments started.

"I was able to hold it away from my body while filling it up and hold it all day," says Jennifer. "This spring, my aunt bought me a new 32-ounce bottle for Easter. It's a bit out of my range, but I can hold it on a lanyard when I'm filling it up."

For Jennifer, these incremental gains are important for her independence. She also has noticed that she is able to open packaging easier and work on craft projects for longer periods of time without requiring rest.

"Before treatments, I could help to a point, but I would get very tired and my arm would be sore. I would have consequences like extra fatigue the next day," says Jennifer. "Now I can continue and then just go to bed. The next day, I could do whatever I wanted because I am not sore or tired."

Complex care in community setting

Jennifer's care team is thrilled with her progress and how offering complex medical treatments in La Crosse can improve the options for patients with other diseases.

"There are a lot of diseases, like Alzheimer's disease, that may have complicated treatments like this in the near future," says Dr. Anderson. "Providing Spinraza treatments in La Crosse laid the foundation and demonstrates how we can tackle a difficult medicine that needs special monitoring and administration in a small community. So when complicated treatments are developed for other diseases, we know we can do that right here."

Oral treatment

In February 2021, Jennifer was able to switch to a newly approved daily oral medication called risdiplam (Evrysdi).

"Some patients with spinal muscular atrophy have difficult spines because of muscle weakness, and, so, it can be tough to perform a lumbar puncture over time," says Dr. Anderson. "That's the advantage of the oral medication that's now available."

Jennifer appreciates the ease of the new treatment.

"I take it after dinner each night. Dr. Anderson said that it might not taste very good, but I told him it would taste better than a lumbar puncture," she says with a laugh.

Looking forward

While Dr. Anderson describes Jennifer as an optimistic and appreciative person who celebrates every improvement, she explains that she wasn't always that way and struggled with mental health in her younger years. Her outlook changed after rededicating her life to her Christian faith seven years ago. Now she is celebrating every day that she keeps her moving forward.

"At my last exam, there wasn't much chartable difference, except in my hand," says Jennifer. "Dr. Anderson said he wasn't sure if I would consider that good news or not. With this disease, every day there isn't a loss is a good day. Every day you don't lose, you are winning."

This story also appears on the Mayo Clinic Health System Hometown Health blog. You can find it there and share it with others.