-

Research

Study may improve understanding of how disability develops in MS patients versus those with related diseases

ROCHESTER, Minn. — Did you know multiple sclerosis (MS) means multiple scars? New research shows that the brain and spinal cord scars in people with MS may offer clues to why they develop progressive disability but those with related diseases where the immune system attacks the central nervous system do not.

In a study published in Neurology, Mayo Clinic researchers and colleagues assessed if inflammation leads to permanent scarring in these three diseases:

- MS.

- Aquaporin-4 antibody positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (AQP4-NMOSD).

- Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody associated disorder (MOGAD).

They also studied whether scarring may be a reason for the absence of slow progressive disability in AQP4-NMOSD and MOGAD, compared with MS.

"The differences in scarring that we found will help physicians distinguish these three diseases more easily to aid in diagnosis," says Eoin Flanagan, M.B., B.Ch., a Mayo Clinic neurologist and senior author of the study. "More importantly, our findings improve our understanding of the mechanisms of nerve damage in these three diseases and may suggest an important role of such scars in the development of long-term disability in MS."

In all three of the diseases, the body's immune system targets the brain, spinal cord and optic nerve. This causes inflammation and leads to removal of the insulation around the nerves or myelin, called demyelination. Visual problems, numbness, weakness, or bowel or bladder dysfunction are common symptoms. Areas of demyelination, known as lesions, appear as white spots on an MRI. The repair mechanisms within the body try to reinsulate the nerves and repair the lesions, but this may be incomplete, leading to a scar that remains visible on future MRIs. Just like an electrical cable without its insulation, this scar may leave nerve fibers vulnerable to further damage and to degenerate over time.

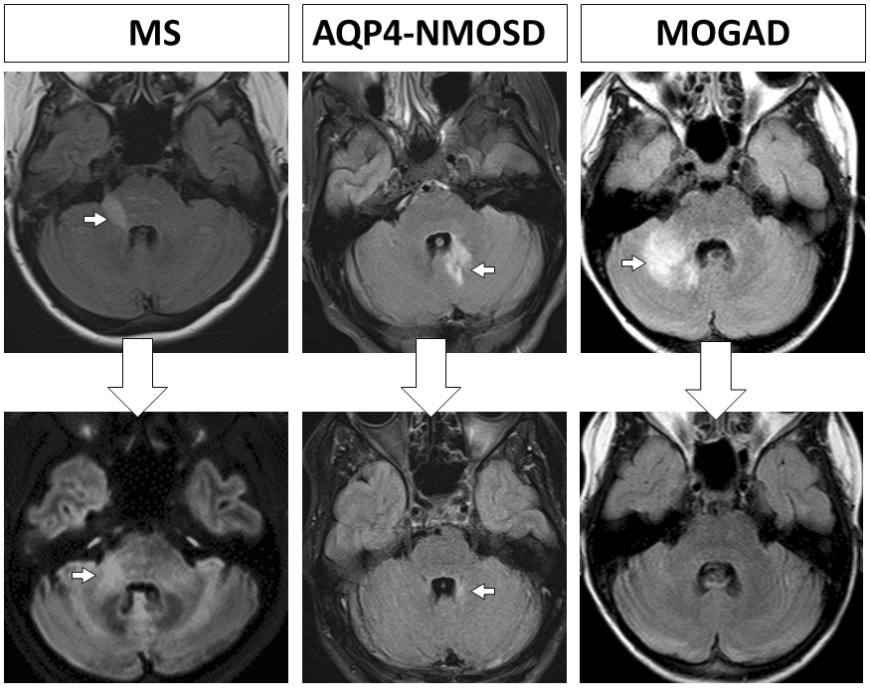

Bottom Row: Follow-up MRIs months to years later show the MS lesion leaves a moderately sized scar, the AQP4-NMOSD lesion leaves a small scar and the MOGAD lesion resolves completely without forming a scar.

The study included 156 patients, consisting of 67 patients with MS; AQP4-NMOSD, 51; and MOGAD, 38. These patients had172 attacks, or relapses, combined.

With MS, the researchers found that areas of inflammation reduced only modestly in size and led to a moderately sized scar. When scars are in regions of the brain and spinal cord that control arm and leg muscles, nerve fibers can degenerate and lead to slow worsening of disability in the secondary progressive course of MS.

"Our study highlights the importance of the currently available MS medications that very effectively can prevent attacks, new lesions and subsequent scar formation" says Elia Sechi, M.D., a former Mayo Clinic fellow and first author of the study. Dr. Sechi is now at the University of Sassari in Sardinia, Italy.

But AQP4-NMOSD and MOGAD are different from MS in that they do not have the same slow worsening of disability typical of the progressive course in MS.

With AQP4-NMOSD, large areas of inflammation occur during attacks, which often results in severe symptoms and permanent problems from poor recovery from the attack. However, the scars visible on MRI tend to be smaller than in MS and may be a clue to why they don’t generally develop the secondary progressive course.

With MOGAD, despite having large areas of inflammation during an attack, the researchers found lesions tended to disappear completely over time and not leave any scar. This fits well with the excellent recovery from episodes and overall good long-term prognosis without the slow worsening disability seen in MS.

The reasons behind this recovery are not clear, the researchers note. They speculate that it may suggest an enhanced ability to put the covering back onto nerves, or remyelination.

"We hope that the improved understanding on the ways MOGAD repairs its lesions so well may lead to novel treatment avenues to prevent scar formation in MS," Dr. Flanagan says.

Other Mayo Clinic researchers involved in this study are Karl Krecke, M.D.; Steven Messina, M.D.; Sean Pittock, M.D.; John Chen, M.D., Ph.D.; Brian Weinshenker, M.D.; A. Sebastian Lopez Chiriboga, M.D.; Claudia Lucchinetti, M.D.; Nicholas Zalewski, M.D.; Jan-Mendelt Tillema, M.D.; Amy Kunchok, M.D.; Padraig Morris, M.B. B.Ch.; James Fryer; Adam Nguyen; Tammy Greenwood; Stephanie Syc-Mazurek, M.D., Ph.D.; and B. Mark Keegan, M.D. Marina Buciuc, M.D., formerly of Mayo Clinic and now of Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, and Salvatore Monaco, M.D., University of Verona, also contributed.

This research was funded by the Gianesini Research Grant from UniCredit Foundation and University of Verona, Mayo Clinic Center for Multiple Sclerosis and Autoimmune Neurology, and the National Institute of Health's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS113828).

Dr. Flanagan reports research support as a site principal investigator in a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of inebilizumab, a CD19 inhibitor, in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders funded by AstraZeneca and Horizon Therapeutics.

###

About Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit organization committed to innovation in clinical practice, education and research, and providing compassion, expertise and answers to everyone who needs healing. Visit the Mayo Clinic News Network for additional Mayo Clinic news. For information on COVID-19, including Mayo Clinic's Coronavirus Map tracking tool, which has 14-day forecasting on COVID-19 trends, visit the Mayo Clinic COVID-19 Resource Center.

Media contact:

- Susan Barber Lindquist, Mayo Clinic Public Affairs, newsbureau@mayo.edu