-

Cardiovascular

#ThrowbackThursday 1982: PACEMAKER Testing Brings Calls From Around the World

This article first appeared May 1982 in the publication Mayovox.

PACEMAKER testing by telephone brings calls from around the world.

Registered nurse Sharon Neubauer , East 16, never knows what country might be on the end of the line when she picks up the phone. “This call’s from Saint Marys Hospital,” she commented recently, “but it could have been Uruguay or Turkey. Our patients are everywhere.”

Ms. Neubauer is one of four registered nurses working with the Pacemaker Clinic on East 16 and at Saint Marys Hospital. Thanks to the wonders of the computer age, she and her colleagues Jane Trusty (supervisor), Rita Kelly and Janet Christiansen are able to check the performance of cardiac pacemakers from all over the world—by telephone.

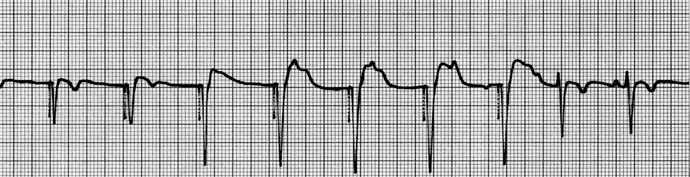

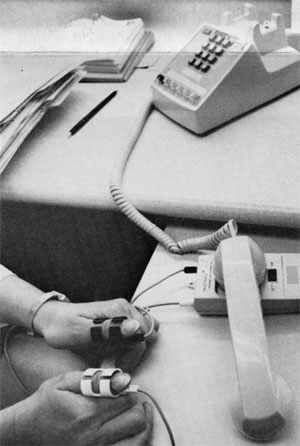

Fortunately, language isn’t a barrier: special transmitters issued to patients at the time of their pacemaker implant “pick up” the patient’s pulse beat and code it into a series of blips and bleeps that “sound like crickets chirping,” according to Ms. Neubauer. The same in any language, these blips and bleeps are automatically fed through the telephone receiver into a special electrocardiograph machine on the Mayo end of the telephone connection.

Every morning the Pacemaker Clinic receives a 15 to 20 routine call from patients whose heart beats depend on electronic stimuli from implanted pacemakers. What the blips and bleeps indicate are the rate and regularity of the heartbeat—to be sure the artificially stimulated rhythm matches the originally “prescribed” for the patient. Pacemakers are man-made objects,” Ms. Neubauer explains. “They’ve been known to fail.”

A Mayo employee since 1973, when she started at the “heart station” at East 16-B, Ms. Neubauer was in on the beginning of the Pacemaker Clinic phone system in October of 1977. In those relatively few years, she’s seen the pacemaker shrink from a nearly palm-of-the-hand-sized object to a sleek-looking compact easily mistaken for a Scandinavian cigarette lighter.

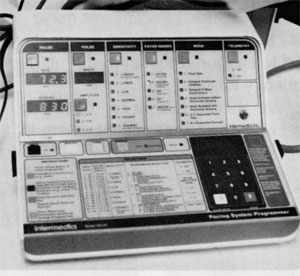

Changes inside the device have also been significant: the new pacemakers can be “reprogrammed” – that is, set to a different rate, etc. by remote control. Thus it’s no longer necessary to remove the device from inside the patient’s chest to adapt it to changes in the patient’s needs.

The life expectancy of an electronic pacemaker is five to ten years. Programmed to tell the monitor when its batteries are going to begin to run down, the pacemaker communicates coded “symptoms” of battery failure in its electronic signal pattern. These are picked up during th

e Pacemaker Clinic’s routine telephone checks—another important reason for the service.

With 950 pacemaker patients – 90 percent of Mayo’s total implants—calling in every three months, the Pacemaker Clinic’s telephone keeps busy. (During the first month after implantation, patients are requested to call in once a week.) To manage the work load and to be sure the checks are made regularly, patients are assigned specific mornings on which to call. Their pacemaker files are on hand as though they were coming to Mayo Clinic in person. Reviewed and signed by a physician, reports on each check are filed by Pacemaker Clinic secretary Darlene Miller. Ann Dreblow, secretary at Saint Marys, maintains a supply of pacemakers and registers implants with pacemaker manufacturers.

In the afternoon Pacemaker Clinic nurses see patients—those whose pacemakers need to be reprogrammed by means of the remote control computer consoles and those whose pacemakers are new.

“One to three months after the implant we examine the incision, review use of the telephone monitor equipment, and make sure patients understand what they can and can’t do.” (Contact sports and arc welding are out; microwave ovens pose no special hazards.) Pacemaker nurse Rita Kelly provides initial pacemaker and telephone orientation during the patient’s hospital stay.

“We also find, both on the phone and in person, that patients seem to find it easier to ask a nurse what they think of as ‘stupid questions’ than they would a physician. They’ll say, ‘I don’t know if I’m having trouble with my pacemaker, but …’ Then we’ll ask what they’re feeling and, often, encourage them to talk to a physician about it.”

Headed by Dr. David Holmes, Drs. James Broadbent, John Merideth, Michael Osborn and Ronald Vlietstra work with the Pacemaker Clinic. The service is staffed 24 hours a day, with night calls taken by monitoring technicians at 4-D North, Saint Marys. Night nurses there are responsible for interpreting results.

Increasingly, telephone transmitters designed for pacemaker checks are also being used by patients with other kinds of cardiac rhythm problems. When such a patient feels the need, he or she can telephone the Pacemaker Clinic for a long distance electrocardiogram and interpretation at any hour of the day. “We have about 100 of those kinds of cases,” Ms. Neubauer estimates.

Although the average pacemaker patient is 70 years old, the nurse has seen patients as young as 30 days and as old as 98 years. (“Though that wasn’t his first pacemaker,” she adds.) The implantation procedure is done under local anesthetic; operating room technologists Lisa Kroening, Jeanette Grabau and Colleen Byrne assist the cardiologists at Saint Marys Cardiac Laboratory. Pacemaker nurse Jane Trusty is responsible for troubleshooting the pacing system in the operating room. With 300 to 400 procedures per year, Mayo is one of the largest pacemaker implant centers in the country.

While patients do call here from all over the U.S. and the world, the majority come from the Midwest. “As winter comes on we start getting a lot of calls from the Sun Belt,” Ms. Neubauer says with a grin. “The patients go South for the winter. I tell them it’s not fair. We have to stay here and answer the phone!”