-

Health & Wellness

#ThrowbackThursday: Mayo lends a hand to a rare bird

This article first appeared in April 1987 in the publication Mayovox.

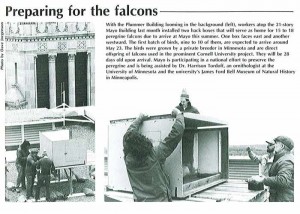

The Clinic joins a national effort to help the endangered peregrine falcon make a comeback. Mayo is lending its stature and its pigeons in an effort to help a rare wild bird get a fresh start in Minnesota.

This summer, 15 to 18 young peregrine falcons will be released from the roof of the Mayo Building to learn to fly and hunt in the wide open spaces over Rochester.The hope is that some of these birds will take up permanent residence in the state.

The releases are part of a national effort to reestablish the peregrine in its natural habitat. The peregrine once lived along the bluffs of the upper Mississippi River and along Lake Superior, nesting on ledges of high cliffs and chasing down its prey — other birds — over expanses of open water.

The releases are part of a national effort to reestablish the peregrine in its natural habitat. The peregrine once lived along the bluffs of the upper Mississippi River and along Lake Superior, nesting on ledges of high cliffs and chasing down its prey — other birds — over expanses of open water.

But the widespread use of the pesticide DDT in the 1950s and 1960s spelled the bird’s doom. DDT affected the bird’s reproductive system, causing the peregrine’s eggs to become so fragile they broke before hatching. As a result, by the early 1960s there were no peregrines anywhere in the eastern United States.

In 1972 the use of DDT was banned and shortly thereafter efforts began to bring the peregrine back. Minnesota’s program began in 1982, with a goal of reestablishing 21 breeding pairs of peregrines in their traditional aerier (lofty nesting sites) in the state. Ninety-two young peregrines, offspring of birds raised in captivity, have been released at three sites: Tofte on Lake Superior, a skyscraper in downtown Minneapolis and the Weaver dunes area near Wabasha.

Some of the birds released earlier at Weaver are now returning to the Mississippi River valley to nest. These birds are quite “territorial” — they view other peregrines within 10-15 miles of their nest site as competitors and will chase them away. This is forcing the closing of Weaver as a release site this year.

When the directors of the program looked around for a new site to replace Weaver, Mayo rose to the top of their list,for a number of reasons:

the 300-foot-high Mayo Building and the updrafts of air around the downtown complex approximate the natural cliff environment that peregrines prefer; food, in the form of pigeons and starlings, is abundant;

natural enemies, principally great horned owls and raccoons, are lacking; it’s close to the Mississippi, where it is hoped the birds will eventually settle; lots of people can enjoy watching the peregrines.

Mayo was happy to cooperate, says Gary Hayden of Facilities Services, in part because the falcons might help control the pigeon population around the complex. “They probably won’t eat that many birds, but they’ll sure scare a lot of pigeons,” he says. But mostly, he says, Mayo was willing to participate just to be helpful and “because we could have a little fun doing it.”

The fun will begin in early to mid-June when the first shipment of six young peregrines will be brought to Rochester. The birds will be about a month old. Their new home will be a four-foot by five-foot wooden box called a hack box, which will be located on the east wing of the Mayo Building roof.

After about 12 days, handlers will free the birds to allow them to explore their new aerie and test their wings. Once the birds are flying comfortably, a new batch of young birds will move into the hack box. After about six weeks of flying the birds should be able to capture their own food. From then on, they will be on their own.

Most of the birds will migrate South in the fall, although one or two birds may remain for the winter if the hunting is good. It is possible that a pair could eventually choose the Mayo Building as a permanent nest site.

Plans are to release 15 to 18 birds here each year for the next two or three years. After that period, returning territorial adults become a threat to further releases. -- written by Michael O’Hara

Related Articles