-

Cancer

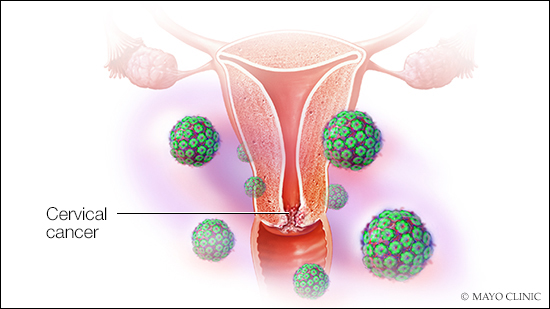

Toolkit for reducing cervical cancer risk

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women globally, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. In the U.S., cervical cancer is no longer a common cause of cancer death because of the use of a screening test called a Pap smear, which detects changes in cervical cells.

While the overall rate of cervical cancer in the U.S. is declining, the number of people diagnosed with late-stage cervical cancer is increasing, and rates among Black women are disproportionately high. Research also indicates that many women still are not being screened for cervical cancer.

Kristina Butler, M.D., a Mayo Clinic gynecologic oncologist, discusses the tools available to reduce your cervical cancer risk, including a trusted healthcare professional, the HPV vaccine and regular screening:

Tool No. 1: Find a healthcare professional you trust.

Many people in the U.S. don't have a healthcare professional they see regularly. The causes are complicated and include being underinsured, barriers related to cost and transportation, and mistrust in the healthcare system — all of which can lead to late-stage cervical cancer diagnoses and poorer outcomes.

"People need to find a care professional they're comfortable with. Catching changes in the cervix and cancers early improves long-term outcomes," says Dr. Butler.

If you don’t visit a healthcare professional regularly due to cost or lack of insurance, you may be eligible for free or low-cost screening through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program NBCCEDP). A program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the NBCCEDP helps people with low incomes who do not have adequate insurance gain access to breast and cervical cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment. Find a screening program near you.

Your local health department or women's clinic may also provide free or low-cost options for screening. The CDC website offers lists of health departments that you can search to find resources in your area.

Dr. Butler recommends establishing a relationship with a healthcare professional you see for a checkup once a year — a primary care provider or a gynecologist, a doctor who specializes in female reproductive health. "During that visit, it’s important to discuss symptoms and anything you think may be out of the ordinary related to the genital area. That discussion might prompt the need for a pelvic exam. A person should be comfortable requesting an exam because, in many instances, it's hard to define normal."

Tool No. 2: Get the HPV vaccine for yourself and your children.

Nearly all cervical cancers are caused by HPV (human papillomavirus) infection, which can also cause cancers of the vagina, vulva, anus, penis, and head and neck. Getting vaccinated against HPV is your best protection against HPV infection and cervical cancer.

"You can receive the vaccine at age 9, and you may still get some protection if you get it up to age 45. With this vaccine, we're hoping to eradicate cervical cancer and other HPV-related cancers," says Dr. Butler.

The CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for children aged 11 and those under age 26 who were not vaccinated. People younger than 15 can be vaccinated with two doses, six to 12 months apart. People who start the vaccine series later, after age 15, should get three vaccine doses over six months.

Adults 27 to 45 who were not vaccinated should talk to their healthcare professional about the HPV vaccine. Dr. Butler says the vaccine can provide benefits even after you have been diagnosed with changes to cells in your cervix that make them more likely to develop into cancer or you have been exposed to HPV.

"The HPV vaccine is exciting because it gives us an opportunity to prevent cancer," says Dr. Butler. “We can reduce the risk of several cancers with this vaccine."

Tool No. 3: Start cervical cancer screening at age 21 and follow a schedule.

"At Mayo Clinic, we recommend that cervical cancer screening start at age 21 and continue every three to five years, depending on the type of screening performed," says Dr. Butler. "At the time of screening, we do a thorough examination to evaluate multiple areas. We are looking at the vulva, the vagina, the urethral area and the anal area for anything unusual."

In addition to a pelvic exam, your healthcare professional will conduct a Pap smear, which involves collecting cells from your cervix to detect any changes. Mayo Clinic recommends repeating Pap testing every three years for women ages 21 to 65.

Dr. Butler says you should continue screening following menopause, particularly if you have any bleeding. "At 65, if you have had normal screening test results for quite some time, you can have a discussion with your healthcare professional about discontinuing," she says. "But we know that 16% of cervical cancer happens in women over the age of 65."

Women age 30 or older can consider Pap testing every five years if the procedure is combined with an HPV test. Knowing whether you have a type of HPV that puts you at high risk of cervical cancer allows you and your care team to decide on the next steps, which may include monitoring or further testing.

Your healthcare professional may recommend a different screening schedule depending on your risk factors and history of screening results. "A patient may have high-risk factors that require more frequent screening. Examples include people with weakened immune systems or people with a history of cervical dysplasia," says Dr. Butler. "Following hysterectomy, most people no longer need cervical cancer screening. But if they have high-risk factors, they should speak to their doctor because they might need screening with a Pap smear that can be performed in the vaginal area since there is no longer a cervix."

If you've been diagnosed with cervical cancer, Dr. Butler says new treatments are giving more people hope.

"For people with advanced and recurrent cervical cancer, we use chemotherapy and a targeted therapy drug called bevacizumab, which works by blocking a protein called VEGF," she says. "For some people whose cancer has markers for the protein PD-L1, we're able to use pembrolizumab — an immunotherapy drug called an immune checkpoint inhibitor." Pembrolizumab works by binding to the protein PD-1 on the surface of T cells (a type of immune cell). This prevents the cancer cells from weakening the immune system, which can then kill the cancer cells.

"The development of these additional drugs has absolutely improved outcomes," says Dr. Butler.

Story originated from the Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center blog.

Related posts:

- "Mayo Clinic Minute: Cervical Cancer Screening

- "Mayo Clinic Minute: Preventing cancer for future generations of Black families