-

Voices of Mayo: Matthew Horace on Race in America Today

Matthew Horace, Mayo Clinic's chief security officer, shares his experience of growing up under the shadow of bias as a Black man in America, his career as a law enforcement officer, and his thoughts on what each person can do to improve race relations.

Voices of Mayo is a series that highlights Mayo staff and their stories, exploring their diverse backgrounds, the challenges they face, the opportunities they have been given, and their experiences at Mayo Clinic.

As Mayo Clinic strengthens its commitment to eliminating racial bias within its walls and in the communities it serves, staff at Mayo Clinic are sharing their experiences of growing up under the shadow of bias, and how they overcame it. Matthew Horace, chief security officer at Mayo Clinic, talks about his background and how he came to be at Mayo Clinic. Horace is founder of The Horace Foundation Endowment for Criminal Justice Studies at Delaware State University.

As a person of color, growing up in Philadelphia, I was aware at a very early age of over-policing, racism and discrimination. Police abuse was an ordinary element of living. It was the problem we all lived with. I was always told by my parents that no matter how absurd the reason for the stop by police, insults or degradation, to submit and comply so that I could make it home alive. They hoped that I would live to see productive adulthood unlike many of my contemporaries.

Early years

In second grade, I was bused from an upper middle class neighborhood to a solidly middle-class, predominantly white neighborhood. I vividly remember as our yellow school buses pulled up to the school, our welcoming committee consisting of white parents protesting with signs and older teens yelling and throwing things despite a police presence.

When I was old enough to make a decision about my schooling, I returned to my neighborhood high school, and excelled at both athletics and academics, and received several athletic scholarship opportunities to attend college. I chose to attend Delaware State University, one of the nation's Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

I went on to play college football and earned a bachelor's degree in English. In 1982, I was training for the upcoming football season when I was viciously attacked by a Philadelphia Police K-9 Officer and his dog during a parade. I was left on the street, bleeding. The officer didn't stop to provide aid, and didn't arrest me or question me. My parents learned that the officer did not report the attack and that the officers who eventually took me to the hospital reported that I had sustained "unknown injuries." I was also listed as a suspect and not a victim. This was my first direct experience with the "Thin Blue Line" and corrupt policing.

I tried as best I could to never leave people or process the same way that I had found them.

Matthew Horace

I was bitten directly in my Achilles tendon area — the bite became infected, and I was hospitalized for weeks. I was certain that my college football career and scholarship were in jeopardy and that any chances I had of playing professionally were over. I also live with the idea of what probably would have happened if I had fought back against the attack.

Athletics has taught me some incredible lessons regarding overcoming adversity on the field and off. After the K-9 incident, I was determined to jump in, crawl, walk, run, lift and get bigger, stronger and faster. I went back to school assuming my starting role on the football field. I doubled down on my understanding of racial injustice. I decided to enter the law enforcement field in an effort to become a part of the solution.

Being the change

Hoping to be the change that I wanted to see, I entered the law enforcement profession first as a police officer. I later rose through the ranks of the U.S. Department of Justice as a federal agent.

I tried as best I could to never leave people or process the same way that I had found them. I committed to using my position and voice to never remain silent in the face of wrong and never fall short on effort. I used my voice as a frequent contributor to national news and became a published author to be candid and initiate difficult discussions. We all have to get uncomfortable to get comfortable.

I transitioned from law enforcement into corporate and private businesses. Law enforcement is a truly noble calling where the majority of people commit themselves to the safety and security of people they will never meet. I learned throughout my career that the profession is also plagued with racism, implicit bias and imperfect behaviors. I was really shocked when I entered the profession as to how often racial and ethnic slurs were a part of the dialogue among many of my colleagues.

Broadly, we can't talk about obstacles or challenges without talking about racism and discrimination. These are challenges I have faced my entire life both in employment environments and during daily personal interactions. They are mentally and physically draining, hurtful, and even can contribute to co-morbidities.

Always being on, always having to do more, jump higher, be better, and demonstrate greater skills will have long-term impacts on your mental and physical health, as will being the "only one in the room."

I've been the only one in specific environments for so long that my family and I have learned how to turn it into a positive.

I've been the only one in the room for so long that it doesn't matter anymore. Although there are many reasons for it, I and my family have learned that it is not always a disadvantage, just uncomfortable.

The Mayo experience

In 2018, I was contacted by job recruiters as I was in my second post-government executive security role. I began interviewing and was advancing in the process when I saw the Mayo position online and also received a call from a Mayo headhunter. I was familiar with Mayo's well-earned reputation in health care. My next role needed to be about culture, mission and purpose.

After thoroughly researching the organization, I was certain that Mayo was the type of organization whose purpose I wanted to contribute to.

I met amazing people during the interview process and was hopeful that they were as interested in me as I was in Mayo.

I did notice that there was no one who looked like me in the interview process nor did I see very many people who looked like me in the environment. This always becomes an issue when considering taking on a new role but especially when considering relocating to a new area for a job. This didn't discourage me because, throughout my journey, I have frequently been the only one in the room, in a meeting, on an airplane or speaking. It's one of those unfortunate isolating facts, but you learn to overcome it.

I never looked back and have not regretted my decision. Mayo is the greatest organization with the most impactful mission that I have ever worked for.

We all know that to fix a problem you have to acknowledge the problem. We all have to get a bit uncomfortable in order to get comfortable.

MATTHEW HORACE

Mayo staff are some of the world's brightest people in the world, and I believe that Mayo leaders understand academically that being a minority in a majority environment can be challenging. It impacts recruitment, hiring and retention.

At Mayo, dozens of employees have extended the arm of hospitality to my family and me, and we have shared some great times and fellowship. In fact, I don't think that we have received as gracious a welcome in any of our relocation experiences — 10 in total — ever in my career. We are truly humbled and encouraged by the welcome that we have received.

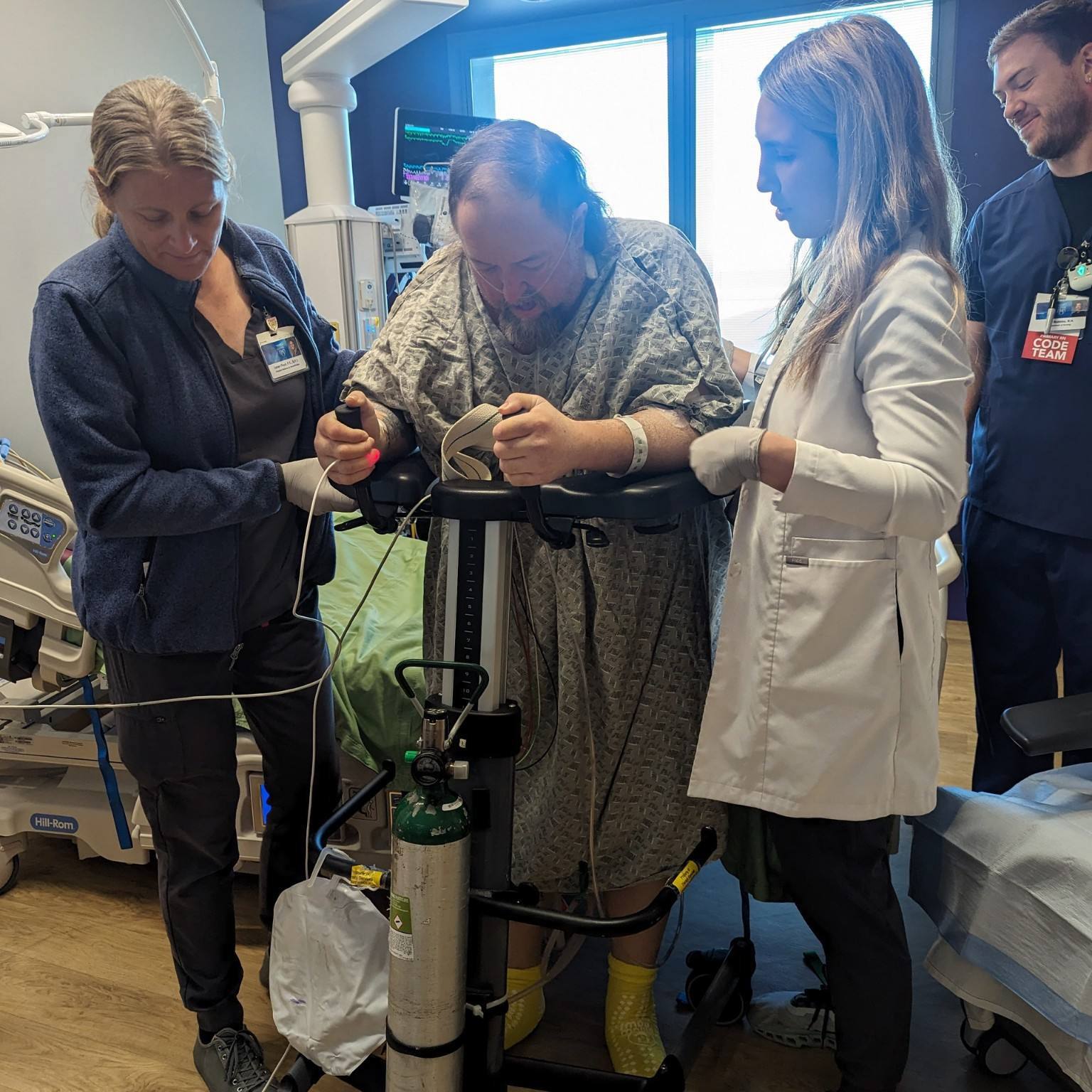

During the Thanksgiving 2019 holiday season, I was hospitalized at Saint Marys Hospital. Three Mayo families gave of their time, talents, money and energy to ensure that despite my hospitalization I and my family had a full Thanksgiving with all of the trimmings. I will never forget the blessing or the joy it brought to my healing.

It is not lost on me, however, that this is not everyone's experience. I would encourage everyone, particularly in times like these, to step out of your comfort zone and ask someone who doesn't look like you to meet for dinner or coffee. This is where the healing begins. Many of my friends call me and ask, "What can we do?" My answer is always the same. "You are doing it."

Getting uncomfortable to get comfortable

We all know that to fix a problem you have to acknowledge the problem. We all have to get a bit uncomfortable in order to get comfortable. Until recently America seemed unwilling to acknowledge racism as systematic and insidious, instead of using terms like "a few bad apples."

Implicit biases don't make us bad people, they just make us people. Unfortunately, when they manifest themselves in the execution of policing and public safety services, those biases can play out negatively. People who shouldn't have to go through this struggle end up feeling drained, exhausted, discriminated at best, or dead at worst.

The world saw this play out in the tragic killing of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, but also in the cases of too many others to mention for the purposes of this story.

In every executive role I've had, I have felt an obligation to ensure that I've given voice and action to issues that have negatively impacted others.

MATTHEW HORACE

While policing has been the target of the nation's current discord, it is important to understand that implicit bias, racism and prejudice exist in board rooms, schools, public service, corporate offices and even in health care.

One aspect is understanding the power of voice in supporting others. In every executive role I've had, I have felt an obligation to ensure that I've given voice and action to issues that have negatively impacted others. Social justice is one of those issues.

To that end, if not me, then who? And if not now, then when?

Social justice is not just about Black people, social justice is about all people. If we were all doing the right thing for the right reasons, we wouldn't be in the current predicament.

I am mindful every day while leading Mayo's Global Security that it's my responsibility to ensure that our operations reflect a mindful understanding of this problem and ensure that Mayo's security and public safety arm is aligned with its well-earned reputation in health care.

Lasting role models

One of my greatest joys is the long line of people who I have been able to mentor, coach and lift up. In many cases, they are people who may not have ever received an opportunity were it not for someone who looked like them listening to them and understanding their gifts.

The other joy has been the power of changing people's hearts. It's been my experience that we can legislate behavior — discipline people for committing acts of racism or words or actions that don't align with Mayo's values. What we can't legislate is hearts. Changing people's hearts is where it truly begins. I have been trying to do this through my appearances on national news segments regarding police use of force, race and policing communities of color and as a published author of two books.

I have proudly displayed two pieces of art in my offices and home throughout the years that depict resilience and courage: The Norman Rockwell print called "The Problem We All Live With," and a lithograph of Thurgood Marshall, signed by his son John Marshall.

The Rockwell print depicts four white male U.S. marshals protecting Ruby Bridges, an 8-year-old African American girl who needed the government's protection as she integrated into New Orleans Public Schools in 1960. In the photo, I am moved by the resilience and courage of little Ruby Bridges, but also that of her family. Being a parent and having been exposed to parents from all walks of life for the better part of 23 years, I can't think of one parent who would have allowed their child or themselves to endure what they did for the sake of justice and equality in education. Whenever I think that someone might not like what I say on behalf of justice, I think about her.

Many Americans understand Thurgood Marshall's accomplishments regarding civil rights and being appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court. What I am inspired by is his journey. He graduated from Howard University Law School in 1932, and, as an African American attorney, worked in some of the most hostile environments on Earth. Imagine an African American attorney walking into a police station in Alabama, Mississippi or Georgia in 1935 and asking to see police reports regarding the death of a Black man? Nothing I have ever faced or will face comes close to what resilience and courage it took for him to succeed for decades.

Ask yourself if you would put your child in the position to be the only or one of the only white students in a predominantly African American school, sports team or dance troupe. If you wouldn't, I invite you to ask yourself why. I and others have done it in reverse our entire lives.

Lessons learned

I've learned these three great lessons along the way:

- Every white person isn't out to hurt you and every person of color isn't out to help you. My mentors and advocates have come from all races, genders and nationalities. That diversity of support has helped to advocate, support and propel me. Choose who is in your corner wisely.

- Discrimination can have an unintended consequence of enhancing your body of work. Throughout my work career, I have been made and asked to do more. The unintended consequence of my early disappointments was that, at a certain point, I was more qualified than all of my peers.

- Pick someone who doesn't look like you on a regular cadence and get to know them. Ask them about their lives, their challenges and their dreams. You will probably find that you have more in common than you think with almost anyone you meet.

At Mayo, nothing is more inspiring than being in a meeting solving unique challenges when you are at the table with a diverse group of people from all over the world with different backgrounds. As a patient at Mayo, my care team consists of doctors, nurses and specialists from all over the world. Diversity and inclusion is a necessary business imperative. This is what makes Mayo special. Extend those business interactions to personal relationships.

Holding on to hope

Mayo Clinic provides hope to over one million people from over 150 countries each year. Having been a patient at Mayo and experiencing the listening, compassion, understanding, teamwork and communication from my exceptional care team inspires me with hope that everything is possible.

When I see the tone, tenor and demographics of national and international peaceful protests and Mayo Clinic's willingness to listen, I maintain hope that I work for an organization and with people who will be a part of the solution and not a part of the problem.

I am inspired by the fact that Mayo employees understand what hope, listening and compassion mean and therefore should be able to be the problem solvers, change agents and leaders that the world needs to see.

I am hopeful that my voice, my writing and my perspective will shed light, open dialogue and influence people to just listen.

MATTHEW HORACE

I am inspired by Mayo's commitment against racism. I have the opportunity to work in a world-class organization with world-class subject experts in their fields. Why shouldn't it be Mayo at the tip of the spear in solving "The Problem We All Live With?" Why can't Mayo solve both the COVID-19 crisis and the social justice challenge of our time?

For those of you who may be wondering, "What is this all about anyway?" African American families in the U.S. are disproportionately impacted by inequities in economics, housing, education, transportation and health care.

I am hopeful that my voice, my writing and my perspective will shed light, open dialogue and influence people to just listen.

Related Articles